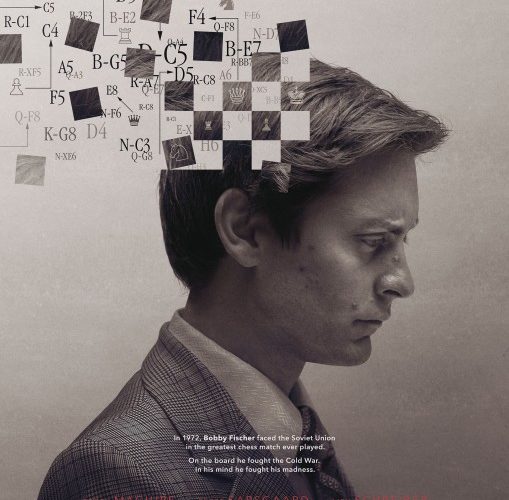

I’ve always been fascinated by Bobby Fischer due to his vanishing rather than anything he accomplished at a chessboard. I’ve never been good at the game, yet I respect its complexity. The greats literally memorize past matches and maneuvers, so in-tune with the playing field that they can play out loud with nothing more than words. Fischer was a great—the youngest Grandmaster in history and the first American-born World Champion. Like most geniuses, however, the strain of intellect, pressure, and success brought with it a hefty price. For Bobby it was the deterioration of his mental health. And as it’s told in Edward Zwick‘s Pawn Sacrifice, he may have known this from the beginning. If he were to rise to the top, the time was now.

My knowledge of the man was always miniscule: a footnote to a 1980s film I watched religiously called Searching for Bobby Fischer. The height of his legend came before I was born so this is hardly surprising, but how can you not be captivated by a bona fide hero who left it all behind? To me he was an enigma. To the government an enemy of the state after playing a rematch with Boris Spassky years after his retirement, forcing exile to Iceland before passing away in 2008. To the world in 1972 he was the most important figure in sports—a one-man stand-in for the United States who took on the entire Soviet Union and won. His story deserved a worthwhile biography and Hollywood has complied.

It begins with paranoia. Fischer (Tobey Maguire) is holed up in his room, listening to everything as though the volume has been turned to eleven for him and him alone. He’s just forfeited Game 2 of the World Championship Finals with Spassky (Liev Schreiber), fearful he’s being monitored and cataloged by the KGB. It’s his looking out the window at a man with a camera that transports us two decades earlier to a similar event. Apparently Bobby has been fighting the Communists for years, his mother (Robin Weigert) a sympathizer whose boyfriends became a steady stream of enemy combatants because they ruined his concentration. Self-taught in Brooklyn, Fischer’s rise was swift and deliberate. It came with an incorrigible ego and abrasive attitude that perpetually risked ending everything.

Steven Knight‘s screenplay and Zwick’s direction do a good job pushing through these early years in a well-paced quasi-montage with 1951 Bobby wowing his teacher Carmine (Conrad Pla) and teenage Bobby taking on eight players at once before transforming into Maguire’s mainstay. We get a sense of his unraveling: the unshakable penchant to latch onto innocuous details and refuse to let go and his insane demands to ensure his success. This was a volatile young man who understood his worth and preyed upon those who wanted him to win more than he did. Cocky from the age of eight, he “knew” he was the best and believed he had nothing to prove. If the Chess Federation wanted evidence, they would have to comply.

In this respect Fischer’s life is shown as a war with himself. Strip away the Cold War overtones, agent/lawyer Paul Marshall’s (Michael Stuhlbarg) connections with the White House to position him as the patriotic story he’d become, and the mystique of the Russian game with Spassky at the lead and we have a lost young man drowning under his own expectations. His trajectory is riddled with self-sabotage and match suicide. Chess is his life and we see it in these actions because he knows winning everything and beating everyone is synonymous with death. At that point the game itself would be defeated and Bobby would have nowhere else to go. He screamed the world was against him, but reality proves it was just himself all along.

The film’s full of interesting characters met along the way including a California prostitute (Evelyne Brochu‘s Donna) and Bobby’s “coach” Father Bill Lombardy (Peter Sarsgaard). No one ever understands Fischer—least of all Stuhlbarg’s Marshall despite his putting every ounce of energy into trying—but Donna and Bill come closest. My definition of close is their refusal to simply give in to his demands or his adversarial nature, especially Lombardy. Sarsgaard is the second best part of the film as a result, a walking contradiction that discovers faith in Fischer to be a tough commodity to keep. He knows exactly who Bobby is and he knows none of this can end well. But he must continue forward because he also knows Fischer’s gifts deserve their opportunity.

Pawn Sacrifice‘s best part is of course Maguire giving possibly the most powerful performance of his career. His Fischer is tightly wound and at risk of bursting at any given moment. He often does too, blowing a gasket with a verbal tirade or retreating so far into his head that nothing’s safe and everything a potential weapon to be used against him. Maguire excels at portraying this increased paranoia and fear—wide-eyed and distant as though a wall exists between him and those with whom he’s forced to converse. So quick to request impossible demands, his surprise when they’re met elicits a quiet, “Right.” In a fog until he isn’t, his psychological and emotional spectrums find their polar ends in a constant state of overlap.

We invest in the journey because of this, forgiving his attitude because his genius needs the freedom of an uninhibited mind to excel. You can’t subdue him like the calm and collected Spassky because it isn’t who he is. Fischer craves spontaneity as game plan and that lack of filter playing is mirrored in his choices away from the board. Both the drama and tension rise to a fever pitch until the championship match gets underway with its sudden starts and stops. And somehow this circus delivers the most engrossing sports tournament I’ve seen onscreen in years. Zwick renders the chess as riveting as any major league event while the story shows how the game became an overnight phenomenon. Fischer provided hope just as his own disappeared forever.

Pawn Sacrifice is now in limited release.