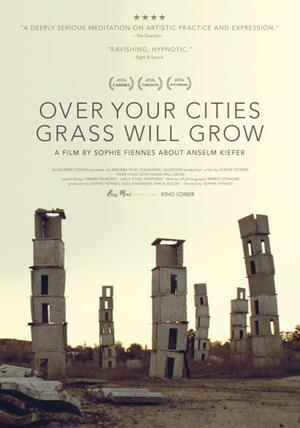

Opening with long meditative, carefully composed tracking shots through tunnels, passages and man-made caves, Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is a portrait with little context of the artist Anselm Kiefer. We learn in text Kiefer moved from his native Germany to Barjac, France, the studio where this work has been filmed.

The film sheds light on an experience in a way that a TV documentary on the same subject perhaps could not. However, like all cinema this is a manipulated experience that contains as much filmmakers Sophie Fiennes hand as it does Kiefer’s. The experience of the work cannot be replicated in Fiennes’ carefully composed frames and tracking shots, all intensified with a musical score lacking subtlety.

Kiefer’s work had been previously unknown to me, an advantage in that the film invites you to do discover his work and process with little commentary, aside from an interview he does on camera with a member of the art press. There are some artist portraits including Alison Chernick’s Matthew Barney: No Restraint and Marion Cajori’s Louis Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine and Chuck Close, that allow the artists and work to speak simultaneously, taking away agency from art critics while serving as a skeleton key into both their process and a life that informs their process.

Anselm Kiefer’s process, haunted by a war torn Europe, evokes the film’s beautiful title. he creates work with materials that shift forms including lead, glass, dirt, and coal – creating sculptures in a variety of forms from caves and ravines to towers of concrete. The film’s structure both explores the space of Kiefer’s work and provides some behind-the-scenes moments of its creation, meditating on process. The horror is not without joy in the creation, however watching the construction of pieces adds deeper meaning to the objects evoking an anger of the past.

The film itself is somewhat effective as we get the sense Kiefer’s quiet presence wouldn’t match the energy of Fiennes’ previous subject, Slavoj Zizek (but who could?) in her mini-series The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. There is no conspiracy here with Kiefer, who is disconnected from the camera, often framed in the distance. Fiennes’ film evokes a problem that some film scholars have with Fredrick Wiseman: his camera is the “eye of god” – while he doesn’t intervene its inevitable he is a mediator (cutting 90 hours of footage into 3 hours).

The film itself is somewhat effective as we get the sense Kiefer’s quiet presence wouldn’t match the energy of Fiennes’ previous subject, Slavoj Zizek (but who could?) in her mini-series The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. There is no conspiracy here with Kiefer, who is disconnected from the camera, often framed in the distance. Fiennes’ film evokes a problem that some film scholars have with Fredrick Wiseman: his camera is the “eye of god” – while he doesn’t intervene its inevitable he is a mediator (cutting 90 hours of footage into 3 hours).

Fiennes’ approach is less “eye of god” and more subjective, especially in its use of music, a choice over natural sound. The film does not intend to be a replication of space – it is not a work of cartography, but what it is, is something that could be slightly more problematic. This however isn’t the only way to experience this work, but for now it’ll be the closest I’ll come to it.

We view as it exists in the wild, and one day grass will grow and overtake these creations. Would existing in a sterile white walled gallery or contemporary art museum be the best representation of this space? This is a question I cannot answer. The film doesn’t fully succeed, but the stimulating conversation that arises afterwards over coffee or a non-fat frozen yogurt bar (in my case) is worth the price of admission.