Laurie Simmons may be new to feature filmmaking, but she is a veteran of the arts scene. A graduate of the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, she moved to SoHo in 1973 and soon thereafter commenced the phase of her photography career for which she would be most well-known: the shooting of dolls that have been lit and arranged within a miniature domestic space in a manner that resembled actual images of people within their homes. From the 1980s onward, she expanded on her interest in dolls in various ways, from a series on male ventriloquist dummies to works featuring “walking objects”—large props worn by her friend Jimmy de Sana—to the 1997 Music of Regret series where Simmons commissioned sort-of self-portraits starring a female doll whose face had been made to resemble her own.

The last project is the one that is most widely referenced in My Art, Simmons’ first foray into feature-length film directing. Simmons stars in her own debut as Ellie Shine, a 65-year-old single artist who house-sits for a friend in upstate New York in the hopes that the tranquil setting will provide some sort of creative inspiration. Ellie’s current project involves having her and a few, local, former/wannabe actors (John Rothman, Robert Clohessy, and, in an unexpected appearance, Good Time co-director Josh Safdie) reenact scenes from famous movies, a concept that functions as a cinematic corollary to Music of Regret: both take actual people and surround them with artifice that simultaneously posits the possibility of a new identity—the immaculate body in the case of the doll, the glamour of the movie star in the case of My Art—and cruelly accentuates the unreachability of this ideal. “You can never be Clark Gable, I can never be Marilyn Monroe,” Ellie tells a co-star at one point. “I just want to see what it looks like.”

In addition to expressing an achingly familiar discontent with the mundaneness of life, this act of transposing oneself into different contexts and mediums as a way of discovering what one really “looks like” lies at the heart of My Art. Ellie’s geographical displacement from urban New York to rural upstate is paralleled in her shift in artistic medium; her prior medium of choice had been photography, but now she is working in digital film, a switch that, in an early scene, is framed as marking a belated entry into the 21st century. If it isn’t clear at this point, Ellie is pretty much playing Simmons herself, and My Art is, at first glance anyway, the sort of personal-reckoning-as-vanity-project that aging artists often tackle in an attempt to stave off obsolescence. The transparency of this apparent ploy in My Art and other such works might have, a few decades ago, registered as refreshing candidness, but these days, self-awareness has become a trope unto itself, often facilely employed as a means of deflecting criticism or appearing clever rather than of pursuing genuine self-interrogation.

The thing is, My Art doesn’t feel particularly vain or gimmicky. It avoids grand displays of artistic hubris while at the same time eschewing the propensity for coyness and self-deprecation that appears among artists who seek to regain public favor by disavowing unpopular past works. The film possesses a low-key tone and overall modesty of presentation that, though at points borderline sleep-inducing, departs pleasingly from the trope of the tortured artist who wrestles with inner demons in the direction of the camera. Though replete with the gentle melancholy of missed opportunities and uncertain tomorrows, My Art is mainly about places and process, the experience of chipping away at a large project within a quaint New England town while a smattering of local characters enters into and out of one’s orbit. The film is pleasant without being ebullient, sad without being devastating, cruising along on life’s rhythms sans thematic or aesthetic grandstanding.

At the same time—and this is one of the film’s main fortes—My Art doesn’t look down on Simmons’ past work. On the contrary, the movie goes to great lengths to cite her earlier oeuvre, a gesture that may bespeak mild narcissism for some but to me felt like an honest, refreshingly self-affirming acknowledgment of where one came from and the influence of an artist’s past projects on her present work. In addition to Music of Regret, the film references Simmons’ Color Coordinated Interiors—which used rear projection to establish the backdrop for her dolls—by employing the same technique in virtually all of Ellie’s reenactments. In one moment where the character and her dog are seen paddling and prancing in a swimming pool, the film evokes Simmons’ Water Ballet, which features the artist’s friends doing more or less the same. Ellie, describing her film-related project to a friend, says how it is about nostalgia and memory, motifs that align with her loving, retrospective attitude toward not only the grand canon of cinema but her own, personal creation as well.

Unsurprisingly, the guess-the-movie quality of the film reenactments are a lot of fun. In a charming move, Simmons has the scenes being performed mirror and elucidate character relationships in the real world. In her hat-tip to the famous sprinting scene from Jules and Jim, Catherine is played by Ellie and the titular male suitors by two of Ellie’s co-workers who are friendly with each other but have also both fallen for her. At another point in the film, these same two men act out the legendary ending of Some Like It Hot—in which an unfazed Osgood responds to the revelation that “Daphne” is really a man with “Well, nobody’s perfect”—thus hilariously intimating a homoerotic element to their own relationship. Each man is also given the chance to profess their love for Ellie through performance—one by being the Mr. Peabody to Ellie’s mermaid, the other by playing the aforementioned Clark Gable character opposite Ellie’s Marilyn Monroe stand-in.

Recall that all these cinematic recreations are modeled after the conceit of Simmons’ Music of Regret. Thus, even when referencing staples of French New Wave and classical Hollywood, Simmons keeps part of herself literally in the picture. On one level, this foregrounding of the artist’s presence emphasizes the fact that citation and interpretation, when done right, are not passive channelings of the past but rather active acts of reappropriation and transformation. On another level, Simmons seems to be merging the public and the personal in striking ways, perhaps suggesting both her work’s indebtedness to larger cultural movements and the ways in which we as individuals encounter said movements—and the tide of history in general—in necessarily idiosyncratic ways.

This sense of the specificity of personal experience is beautifully articulated in the film’s final scene, which depicts Ellie at a significant point in her life but fails to betray what she is thinking or feeling. As she leans against a doorway while facing us, one of her actors stands some distance away with his back to the camera, looking at an installation display of the Clark Gable role he’d earlier inhabited. Whereas he is looking back into the past, she is looking forward, but toward what? Her face remains inscrutable, and fittingly so, since any sort of genuine self-discovery, however publicly flaunted, is ultimately a private affair. As cars zoom by in the foreground in smudgy, seemingly step-printed motion, the image comes to evoke the iconic moment from Chungking Express when could-be lovers become suspended in their own, languid time-scale while oblivious pedestrians race by. Like with that instant, past collides with future here in the form of an elongated present that’s pregnant with possibility. Ellie’s story may have ended, but we will be paying rapt attention to where Simmons goes next.

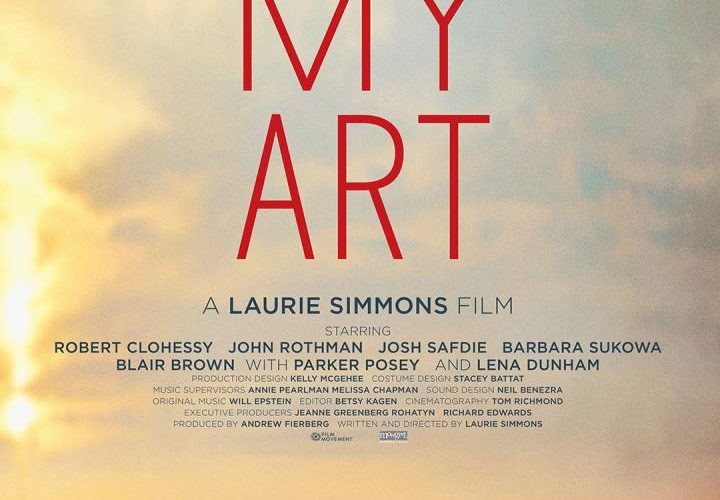

My Art opens at Quad Cinema on January 12.