From the moment an electric guitar’s riff introduces heroine and painter Katsushika Ōi (Anne Watanabe) in 1814 Edo, Japan, Keiichi Hara‘s Miss Hokusai clearly wants us to know that this girl is beyond her time. The musical anachronism tells us as much, but so does the haughty way in which Ōi dismisses the gauche advances of a would-be suitor and the way her voice-over narration signals a self-assuredness not typically attributed to women of her time. The film’s final scene suggests it again, reintroducing the guitar leitmotif while the same, confident narration tells us that Ōi married once but lived her final days untethered to men. As her voice subsides, Edo transforms, via time-lapse, into the Tokyo that we know today, showcasing the modernization of which the real-life Ōi was one of the early figures.

Taken together, these narrative bookends pronounce the spirited independence of this young woman and would have befit a film that foregrounds feminine empowerment. Miss Hokusai is not this film. Aside from a pointed scene in which Ōi finally escapes the shadow of her father, renowned Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai (Yutaka Matsushige), to become one herself, most of Miss Hokusai pays little attention to Ōi’s role as a young woman within a patriarchal society. Perhaps this deemphasizing of her iconoclasm was for the better. If the entire picture had paraded its heroine’s progressiveness like the aforementioned scenes, the resulting work might very well have felt too self-congratulatory, perhaps even downright ingratiating in its attempt to appeal to the viewer’s modern sensibilities. Still, the sharpness in contrast between the majority of Miss Hokusai and the prologue / epilogue pair causes the latter to feel too much like a tacked-on afterthought.

This impression of haphazardness is exacerbated by how the film juggles various plotlines that seem to bear very little relation with each other. Ōi’s fight for her own artistic identity vies for screen time with the estrangement between Hokusai and Ōi’s younger sister (Shion Shimizu), Ōi’s own relationship with her sister, and the film’s self-reflexive meditations on art and art-making. An argument could be made that a narrative disjointedness fits the slice-of-life genre, which foregoes an openly contrived screenplay to emulate the randomness and episodicity of the everyday. This might be the case, but, unlike Miyazaki’s masterful The Wind Rises — an apt point of comparison, given its kindred status as a biographical anime about artists in a modernizing Japan — Miss Hokusai doesn’t use its meandering plot to cultivate a sense of character, time, and place. Rather, the narrative itinerancy seems primarily a way of cramming too many ideas into a 90-minute film, often leaving it dangerously close to feeling both unfocused and underdeveloped.

What saves Miss Hokusai is that some of its ideas are rather interesting. The film fascinates most when it turns its attention to art, such as in scenes that pay tribute to the vividness of imagination. Storm clouds brew as Ōi stresses over completing a commissioned painting, and when she begins drawing a dragon, an actual dragon descends from the sky. Elsewhere, a courtesan is plagued by demonic visions caused by a horrific painting on her bedroom wall, and though this scene was probably intended to convey 19th-century Japanese society’s superstitious relationship with art objects, it could also be a more general paean to art’s ability to move and act in the world. Yet other scenes equate artistic sensibility to a sixth sense, such as when Ōi and her father sit transfixed by a ghostly apparition to the bemusement of their amateur artist friend, who sees nothing. This last point has poignant implications for Ōi’s younger sister, who is blind but whom Ōi constantly helps to “see” through appealing to the little girl’s other senses. Vision beyond vision is a recurring motif in Miss Hokusai, beautifully articulated through the workings of the film’s magical realist world.

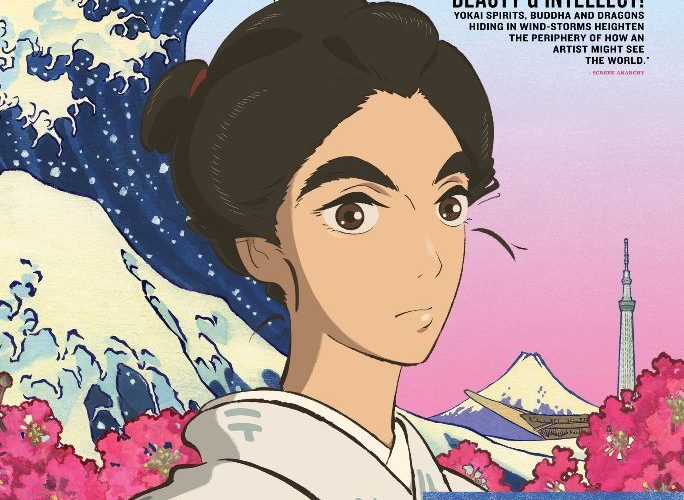

Occasionally, the film seems to turn self-conscious about its own status as an artwork positioned within a long tradition of art-making. A boat ride on the ocean ends with a freeze frame of a wave cresting high above the riders’ heads — an homage to the real-life Hokusai’s famous woodblock print “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.” In this moment, Miss Hokusai has stilled its forward momentum to foreground the anime medium’s own indebtedness to past art forms, which, in turn, invites inquiry into how the film itself was constructed. Another scene depicts a character clowning around while Hokusai records his antics through drawing. It playfully and repeatedly cuts from a shot of the art subject to Hokusai’s ink drawing of the same image, and in this juxtaposition there appears something akin to a deconstruction of the film’s visuals themselves — a movement from the completed, colored film to the kind of rudimentary sketches the animators likely used when storyboarding. Through this scene, there’s a suggestion that its own making is not so different from that of the artworks it portrays.

In its ruminations on artistic tradition, creation, and vision, Miss Hokusai is something close to a minor masterpiece. Its other ideas, though less inspired, also resonate in significant ways. The competitive tension between master and apprentice is an age-old archetype whose continued appearance in popular media speaks to its universality, while the message that women can paint their own destinies is shamefully still relevant, given extant sexism in 2016. The questionable presentation of these ideas detracts from their power, but not fatally. Such is the potency of Miss Hokusai’s themes that, even despite various shortcomings, they fly off the screen like electricity.

Miss Hokusai will be released on Friday, October 14.