There are many types of laughter, the kind coming out during a horror film always a point of interest. Many cope with fear by forcing themselves to laugh, the sound hopefully easing the unrest gradually settling in. This is what good horror strives to achieve, that ability to precisely straddle the line so the audience’s brains don’t know quite what to do. Any genre film able to elicit a nervous laugh is more effective in my mind than one earning screams. Screams are easy; all you need is a bit of shock value when least expected. To coax the mind to the edge and then linger there as mood and atmosphere grow heavier by the second and refuse to release—now that takes a steady, sure hand. Andrés Muschietti may possess one.

I say ‘may’ because the potential is there. He just needs a bit more polish whether he’s earned Guillermo del Toro‘s stamp of approval or not. His feature length debut Mama—based on his three-minute Spanish-language short of the same name—had my theater uttering awkward sounding laughter for a good hour before the seat shifting discomfort made way for louder guffaws. Where the unknown ruled the beginning, turning its malevolent force into a three-dimensional character interacting with the cast sadly brought everything to a halt. Manifesting the demonic presence as a jumble of contorted limbs and flowing hair is a tough sell for the most experienced auteur let alone someone with his first bag of Hollywood money. Turn it into a cartoon and no one will remember how amazing it was inside the shadows one second previous.

Unfortunately, this is the fate Muschietti receives after his chilling start. I didn’t have high expectations and yet the opening scenes held much in common with another del Toro disciple’s debut, The Orphanage. The score, coloring, dream-like flashbacks, evil entity existing to protect, and unwitting family roping themselves into the tragic situation are all included with near equal effect. Watching young Megan Charpentier‘s Victoria stare dead-eyed at the camera and Isabelle Nélisse‘s Lilly crawl around on all fours like a feral animal is creepy to say the least. Knowing these girls survived five years in the woods all alone is sad enough, but seeing their emaciated bodies covered in dirt, afraid of strangers trying to help is heartbreaking. How could Uncle Lucas (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) and his girlfriend Annabel (Jessica Chastain) refuse the chance to show them love?

Oh, I know, maybe because they’re completely off the reservation talking to walls and probably victims of split personality disorders? Perhaps the fact they stayed alive by eating a mountain of cherries and were protected by some impossible figure they affectionately call Mama in whisper? How about Lilly’s desire to eat anything that isn’t edible and Victoria’s penchant for taking her glasses off so as not to see this mysterious protector as more than a blurry shadow passable for a living female? There’s nothing like an over-reaching mother figure going after the woman trying to horn in on her territory and the man who just happens to be the identical twin of one she killed after putting a gun to his daughter’s head. Scary ghosts confuse easily, especially when their children need a savior.

So, like most horrors, the newly introduced parental figures refuse to believe while the psychiatrist/doctor/priest figure chases his leads to discover what’s truly going on. One parent dies or comes ever so close in a coma-inducing ‘accident’, the other finally starts to accept what’s happening, and the third wheel seconds away from uncovering the disastrous secret is silenced. There is nothing new where the backbone of the plotting is concerned, nor is there in the construction of the tar-black, bloody trail-leaving ghoul hiding in the shadows. With dark orifice portals providing safe travel along its journey of death and destruction, one can recall a plethora of previous works Mama‘s visual style blatantly homages to give audiences exactly what they paid to see. What I was interested in, however, were the moments that set it apart.

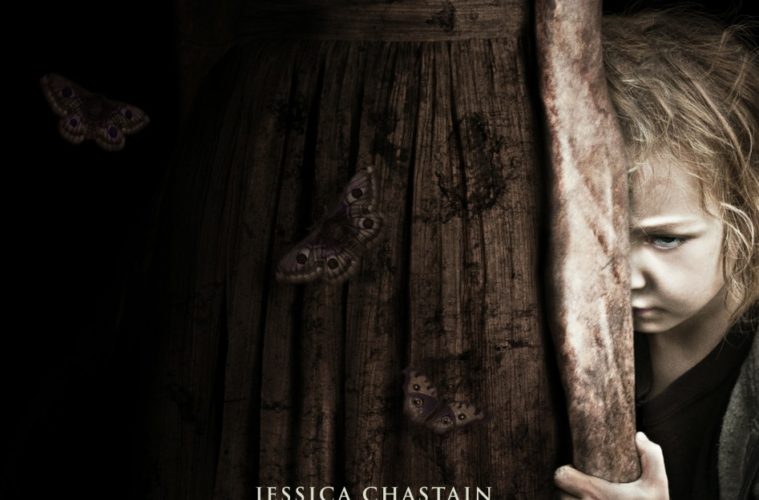

The acting caliber of Jessica Chastain is a major positive, her gothic couture and tattoos providing a look she has yet to perform. I enjoyed her absolute revulsion at the prospect of becoming a mother, her ambivalence to it when forced upon her, and maternal instincts softening when the children needed it most. Her Annabel provides the necessary layers Coster-Waldau’s one-dimensional character of Lucas is never allowed to have. He must give the unadulterated love just as Daniel Kash‘s Dr. Dreyfuss handles the incessant skeptic digging for clues. Annabel is the mother these girls never had—or did in a very warped, unhealthy manner—so they slowly thaw too. Charpentier wonderfully emits her fright in not wanting to upset either woman and Nélisse shares an uncanny ability to be creepy from start to finish.

Add some inspired cinematography and Mama delivers more than not. A couple chase scenes filmed from the height of the little girls disorients and intrigues with each turn through the house and one static shot exposing two rooms at once to reveal more than the assumed three people between them is stunning. If only Muschietti could have sustained this subtlety rather than let his antagonist be in focus and on camera for the final twenty minutes. What was a frightening concoction of ghastly thin arms and fingers amidst wispy fabric and hair turns into a poorly fabricated, unoriginal double-jointed monster. If not for the somewhat surprising natural progression of where the children end up, the movie might have completely derailed. Even so, it’s not enough to forget how good the film was or how quickly it unraveled.

Mama is now in wide release.