Music is an intensely personal thing for many people. We listen to it, assign it meaning, and sometimes build entire moments or stages in our lives around it. Music is a thing that can exist with us, in time with our experience, and enhance rather than overcome it. Sure, music can be turned into a commodity, distilled and diluted into something cynical, but there will always be those who search out the real thing, the passionate and painful art born of those who have nothing else to give the world.

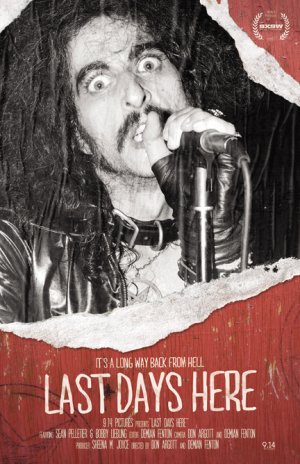

Last Days Here, the latest documentary by Don Argott and Demian Fenton (Art of the Steal), observes one such artist – Bobby Liebling, the lead singer of the heavy metal band Pentagram, who has been lost in a mire of drugs and mental anguish for decades. They watch as family and friends try beyond all hope of success to bring him back to life and limelight, and as Bobby himself struggles against his own worst demons to find the one place he feels at home – the stage.

From this description you would expect this film to appeal only to devoted fans of Pentagram, or at least the heavy metal genre, but in truth Argott and Demian have created a universally appealing and compelling narrative about fame, artistry, tenacity, and the possibility of redemption.

The road is not easy, and for most of it Bobby himself is less a participant in his own salvation than an immovable object to be acted upon. He lives with his parents in Germantown, Maryland. He does copious amounts of drugs and perceives himself to be patient zero for a new kind of parasite that lives in his skin. He retains the trappings of his former glory – the clothes, the records, the memories and dreams – but seems so far removed from them as to be a ghost in his own life. His parents have emptied their hearts and wallets trying to support him, and he has alienated most of his old bandmates.

Sean “Pellet” Pelletier, Bobby’s manager, friend, and fan, seems to be the only one who still believes unfailingly in Bobby’s genius, and sets out to seemingly single-handedly draw him back into music. In this way, through this ambition, Pellet becomes as much of a protagonist as Bobby. Throughout the film we watch him juggle Bobby’s shifting moods and tenuous bouts with sobriety, all the while putting himself on the line to make sure that Bobby has his chance to come back, to rise up and become the performer he used to be. Bobby has come to a point where he doesn’t have much to lose, and so it is harrowing to watch as Pellet puts his own energy and money up as collateral against the chance for Bobby to come back. Come back not only in terms of musical performance, but through that performance back to a life worth living.

Sean “Pellet” Pelletier, Bobby’s manager, friend, and fan, seems to be the only one who still believes unfailingly in Bobby’s genius, and sets out to seemingly single-handedly draw him back into music. In this way, through this ambition, Pellet becomes as much of a protagonist as Bobby. Throughout the film we watch him juggle Bobby’s shifting moods and tenuous bouts with sobriety, all the while putting himself on the line to make sure that Bobby has his chance to come back, to rise up and become the performer he used to be. Bobby has come to a point where he doesn’t have much to lose, and so it is harrowing to watch as Pellet puts his own energy and money up as collateral against the chance for Bobby to come back. Come back not only in terms of musical performance, but through that performance back to a life worth living.

In this struggle, the audience is privy to every moment, every turn of the road. This intimacy turns what could have been a niche film into a broad examination of a very universal theme – of redemption and success in the face of impossible odds. We see people, rather than genre caricatures, and we feel their distress, their joy, and their hope. We may never understand how they can continue to place so much faith in Bobby, but we can definitely understand why; because they see in him the potential for so much more than he has let himself accomplish. By the end, I’ll wager even the most cynical or dismissive audience member will not only see the same potential, but be equally as invested in its possible fulfillment.

This is a well-made, unbelievably intimate film, and should be essential viewing for anyone who loves music, art, or the almost mythic quality of those rare artists who seem to be unable to do anything but create it.

Last Days Here is in limited release beginning March 2nd and arrives on demand on March 16th.