Joy is a small-stakes story told with the highest of energy. Over his last few films, David O. Russell has looked further inward, pushing his ensemble screwball sensibility to the forefront, but it’s often at the expense of storytelling. His latest unfortunately still suffers in telling an engaging, clean tale, but it’s not a case of style over substance. In fact, aside from a few moments of that signature swoop-and-swing filmmaking, there’s very little of the dizzying juggling act found in the director’s previous work.

This, an adaptation of Joy Mangano’s life story, is a mostly linear tale, but one that’s pared down to the most essential (and inessential) parts. And while it’s easy to criticize Joy for not delivering the grandiose, interweaving journey that might be expected from its pedigree, to say so is to overlook the ways that the film uses cinematic and, indeed, anti-cinematic qualities to say things — not only about the modern American Dream, but, more crucially, the varying scale of difficulty for different people to succeed.

This is rags-to-riches, but there’s very little of the rags or the riches. Instead, it exists in a place of purgatorial push and pull, the lows presented with tedious familiarity and the peaks observed from a nearly peripheral vantage point. That’s perhaps attributed to the bizarre choice to have Joy’s grandmother (Diane Ladd) narrate this film, yet the writing and (especially) the editing make a real effort to ground even the most triumphant moments. Even its most climactic point first appears to be accompanied by a bit of magical realism, only to be revealed as a natural structure.

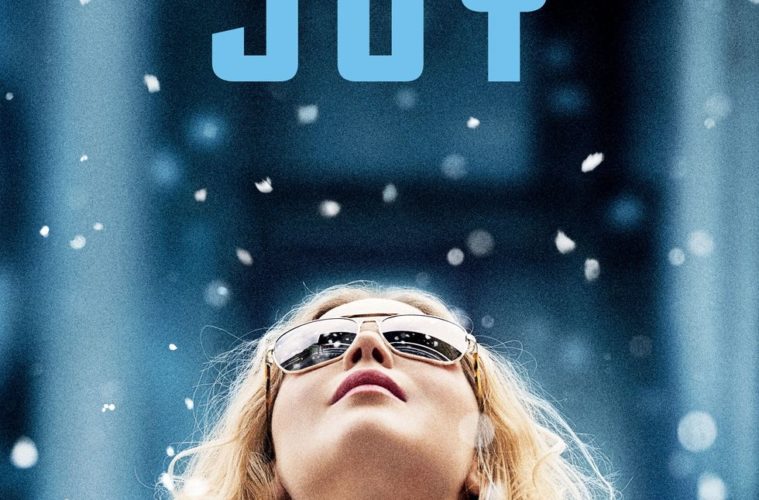

Joy (Jennifer Lawrence) lives in a tornado of a household, dealing with a harried family and brainstorming her next big invention. Down to her own home, which is overflowing with both plumbing and people problems, Joy’s life is in disrepair, and her family is living in a fantasy world of false ambition.

Her ex-husband, Tony (Édgar Ramírez), is freeloading in the basement, clinging to a dream as a Tom Jones-style crooner. Her mother, Terry (Virginia Madsen), is a permanent houseguest who loses her days and nights watching the stories of other people. Her half-sister, Peggy (Elisabeth Röhm), bad mouths her to her children and looks for cracks in her plans. And her father, Rudy (Robert De Niro), starts the film on Joy’s doorstep after leaving his second marriage in ruins.

But despite a boundless inventiveness, her conceptions can’t find a practical root until the introduction of Trudy (Isabella Rossellini), a wealthy widower who Rudy meets through a dating service. Trudy barely exists beyond the fulcrum of the plot, but she steadfastly follows a series of philosophies from her late husband that guide her every business move. Those are the seeds of the creation of Joy’s “Miracle Mop,” a self-wringing mop that was the crown jewel of the real-life Joy Mangano’s career.

Neil (Bradley Cooper) is at the center of the next part of Joy’s life — a bigwig at the still-budding QVC who’s willing to give her a chance. Speaking with a pragmatic, clearly enunciated plainness, he’s a smooth talker, but appears with the veneer of someone who considers their words with the utmost sincerity. His character serves a greater thematic purpose in displaying how “normality” can be a marketable mode compared to his “professional” manner. That doesn’t mean he’s shown with an automatic regality either. The scenes at QVC have a stately drabness — they’re well-ornamented and filled with people, but framed in such a compact context that they can only feel small.

Even in Neil’s big show-off moment as a boss, the orchestration is supplied by two rows of people fielding calls. It’s supposed to be a grand, rousing moment, and is intentionally underwhelming for the audience, even though Joy is gobsmacked by the show of power.

Later, Lawrence is entranced with the television, watching Cooper work his magic. This time, though, the camera remains trained on Lawrence’s face, soaking in every minute variation in her eyes and mouth. These people live with different stakes. For Neil, it’s one deal. For Joy, it’s a lifetime’s burdens on the line.

There’s fits of success and luxury in Joy’s life, albeit ones leadened with moments that force her back down to earth. An ill-planned cruise ends in an impromptu cleaning session, a television break brings out stage jitters, or, worse, a seemingly bulletproof business plan is upended through petty negligence. Joy could be described as the backstage road to fame, for it almost seems to consist entirely of events on the margins.

And while the focus is undeniably centered on Joy’s character, it also maintains an aloofness. She’s in every scene, but as the camera floats around the scenery, there’s rarely a sense that the actions are being seen through Joy’s point-of-view. Shot by cinematographer Linus Sandgren, who brought a self-aware artifice to American Hustle, Joy often feels like an experimental view into a story of struggle.

This distance isn’t the most emotionally insulating style, yet it does lend an unglamorized sheen to the whole proceeding. It’s all Joy inching forward in her goal for acceptance and her attempt to grab a seat at the boys’ table. The first scene at QVC, for instance, isn’t shot with a sense of pageantry, favoring a maze of narcissistic blockheads who are more concerned with their outfits than the products they’re modeling.

Russell wrote the script, acrimoniously adapting — and reportedly taking a hacksaw to — the original story from Annie Mumolo, and the patchwork scripting shows. Scenes that could conceivably be shortened into montage are shown in full, while other superfluous additions are included that have no bearing whatsoever on the plot.

It’s far more difficult to argue for the hollow literalization of subtext. In the most writerly contrivance, Joy is saddled with a recurring thematic dream that ties into the entire impetus for the film. That’s already headed into blunt territory, but the film also feels obligated to show the dream, which is full of ponderous choirs, past selves, and plenty of other pat reverie imagery.

Given the amount of story beats that hobble Joy’s dreams, the film does skirt with feeling miserablist, and both the dialogue and Lawrence’s performance, never let it reach that point. Considering the prestige involved, one appreciates that these performances all feel like snapshots of regular people, and very little capital-A acting. There’s none of Cooper lapsing into a manic-depressive episode or a hippie Lawrence screaming about a toaster. She’s the acting highlight, which is less a result of her performance than a continued testament to her ability to modulate between wrecked vulnerability and ferocious determination without feeling like she’s changing modes.

Until its end, which badly blunders in spelling out a happy ending, Joy is admirably hard-nosed in telling a story about an incredible woman with a great idea who couldn’t find true success without playing the system. It’s an entire film invalidating the bootstraps mentality of America. Hopefully, like Joy herself, it will be taken on its own terms rather than on an assumed reputation.

Joy opens nationwide on Friday, December 25.