There are certain conventions all sports movies must require. In documentary it’s considerably more difficult, as a filmmaker must make choices on who to follow with your camera. In any documentary (or even in any film if we shall get truly technical) the pressure is mounting even more so when it is for a finite. You only get this one shot: a season and/or the tension building to the final round.

There are certain conventions all sports movies must require. In documentary it’s considerably more difficult, as a filmmaker must make choices on who to follow with your camera. In any documentary (or even in any film if we shall get truly technical) the pressure is mounting even more so when it is for a finite. You only get this one shot: a season and/or the tension building to the final round.

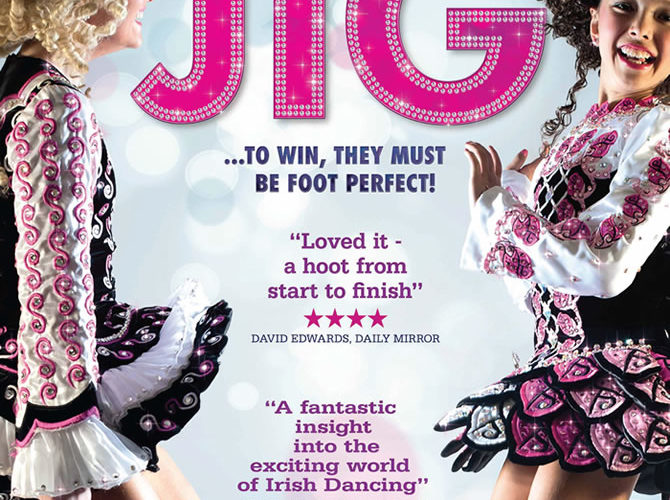

Jig, an audience award finalist from this year’s crowd HotDocs, making its way to theaters in New York and Los Angeles, is not exempt from the conventions that make a sports film crowd pleasing – a tense competition. This time, the sport is Irish Dancing. The film follows several young dancers competing for gold including an American from California who has been transplanted to Ireland by his parents when they discover he has a talent.

There are also the Russians, themselves with a tradition of ballet that gravitate towards the spirit of Irish dancing. However they are denied access to the compaction, due to visa restrictions. Other characters are youth from Ireland, Britain and Holland, some with past successes who have dreams of recapturing the gold before they’re forced into retirement from youth compaction. They dawn colorful custom costumes associated with Lord of the Dance. Michael Flatley is a hero for many young boys, who are suffering from the same pressure as young Billy Elliot: because they dance they are made fun of. Like any sport nothing is easy, and they train as hard as the footballers. The film takes a personal approach introducing us to characters as they train.

Therein lies the problem encountered by Sue Bourne and team. Whom does one focus on? With three thousand of the world’s best dancers descending on Glasgow, whom do you follow – and with what detail? Even the highest stakes gambler wouldn’t take these odds; there is no guarantee that the winner will even be someone that makes for compelling cinema.

A documentary such as Jeffrey Blitz’s Spellbound is the closest analog, having the liberty of qualifying rounds and a more intimate selection where it worked. Here, like in real life, we get to know several contenders from all over the globe (mostly the UK/Ireland) that don’t make it. While hard work goes into any sport there are elements missing from Jig that don’t add up to real tension, mostly because we are introduced to several characters along the way who don’t reappear with as much significance as they arrived.

Much of this is the condition of making a documentary such as this. Despite its limitations its sincere in intention as an alternative sports documentary of cultural value. There isn’t an Irish jig film that makes its way to theaters in the United States every summer. As a window into a foreign world with similarities to the dedication to any competitive sport, it’s a compelling documentary. It is however, not a character study despite functioning as a disjointed portrait, unreasonably wide in scope and ambitions.

Jig is now in limited release.