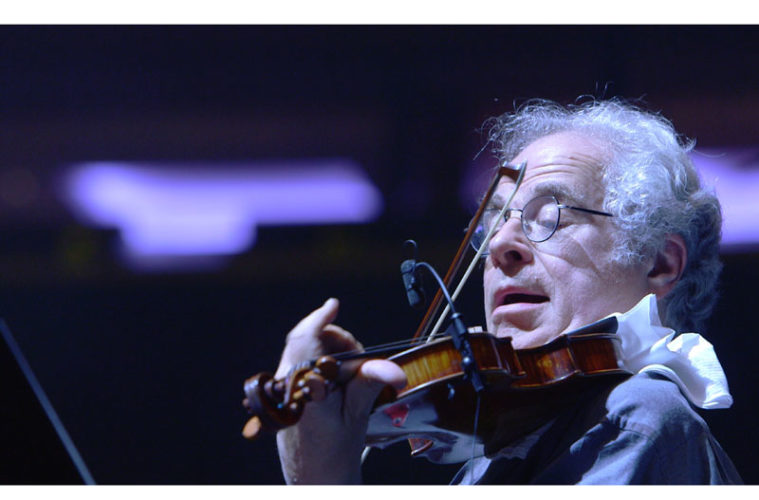

Documentarian Alison Chernick has made a career of profiling artists from Jeff Koons and Matthew Barney in features to Roy Lichtenstein and Rick Rubin in shorts. Her latest subject is renowned violinist Itzhak Perlman — a victim of polio as a child in Israel who found himself at Julliard before earning Grammys, Emmys, and countless international awards. He overcame a disability (walking on crutches when not in his wheelchair) that never impaired his playing, but constantly hung over his head as a psychological hindrance in the minds of those with the opportunity to help his education. It took Ed Sullivan and an assumed desire to showcase a teenaged Itzhak’s skill despite his handicap rather than removed from it to bring him to New York and carve his path forward.

Itzhak is a hybrid of sorts that doesn’t merely draw his linear trajectory from birth to the present or focus on some specific moment in his life today. Chernick follows him around instead, capturing moments that could potentially embody who Perlman is as a man as much as musician. We witness his day-to-day, travel to interesting venues (including a Mets game for the anthem, a Billy Joel concert as a featured instrumentalist, and Israel to meet Benjamin Netanyahu and receive yet another well-earned accolade), and every now and then look back through archival footage and interviews to see and understand his youthful perseverance. At times a love story between Itzhak and wife Toby and others a venture into music’s emotional colors, Chernick’s work simply let’s its subject exist.

This reality can earn ire from some who say the scope is too narrow and others how it’s too generic a construct to truly learn anything, but I think there’s something to letting him speak through his actions. We can learn a lot from watching his interactions with the aging Israeli violin shop owner from his youth or Alan Alda stopping by his NYC home for dinner and conversation. We witness Itzhak’s easy sense of humor, his often silent chuckle that almost makes it seem he’s ready to cry, and the impact music has on him while playing or listening. He explains with full candor how the teaching styles he hated as a child are the ones he has adopted. He’s self-deprecatingly jovial, religious and yet still pragmatic.

These are the things we couldn’t know from interviews and still photographs. We can be told them all — and Toby is never one to shy away from letting the camera know how wonderful her husband is — but it means more to experience them. My favorite part of the film is when we hear Perlman tell pianist Martha Argerich the punch line to an anecdotal joke he already told two fellow musicians much earlier. There’s something so human about his having a go-to joke and being shameless enough to share it with everyone he meets. These tiny details help to portray him as more than just a savant who lives and breaths violin. He’s a father, unabashedly hammy, and confident enough to give Billy Joel notes about his concert.

And when he speaks directly to Chernick we feel like we are learning something. He isn’t teaching us how to play, but he is explaining what it is about music that makes it so powerful for all of humanity. He talks about art as an abstract rather than always having to go back to his own work for context. The beauty of his skill and pedigree is that his art speaks for itself in the many short vignettes throughout. Itzhak doesn’t have to sell us on his motives or ideas. He only has to place a handkerchief over his chin rest and put bow to string for us to understand the piece of music played is rendered less important than how he plays it. His gift is infinite.

This is a truth that some will inevitably find hard to comprehend. It’s much easier to call Beethoven or Schubert a genius because they have left behind concertos that exist on the page as well as in our ears. It’s no coincidence that Chernick includes the dinner with Alda because the comparison of their occupations is so apt. They perform the work of others and yet also create something of their own. Their art is an interpretation. It’s them transcending the sheet (or script in Alda’s case) to breathe life into something and make it universally accessible to the masses. While it may seem like you could go on Spotify to listen to his albums and receive as much as we do from this film, you’d be wrong.

Watching him onscreen removed from his art and yet still so connected to it becomes our education and ultimately inspiration. He needs to travel the snowy sidewalks of NYC with a shovel so his companions can clear a path for his chair. He hobbles to the conducting chair and yet it’s as though he is standing when he conducts with such poise and mastery. He has overcome his ailment not only for himself, but also for those who blindly dismissed him because of it. Itzhak has paved a way forward for future generations to know what it is they are capable of despite any physical limitations. No one with his talent should need to be a gimmick to see it fulfilled. Appearance shouldn’t matter where performance is concerned.

Itzhak is now in limited release.