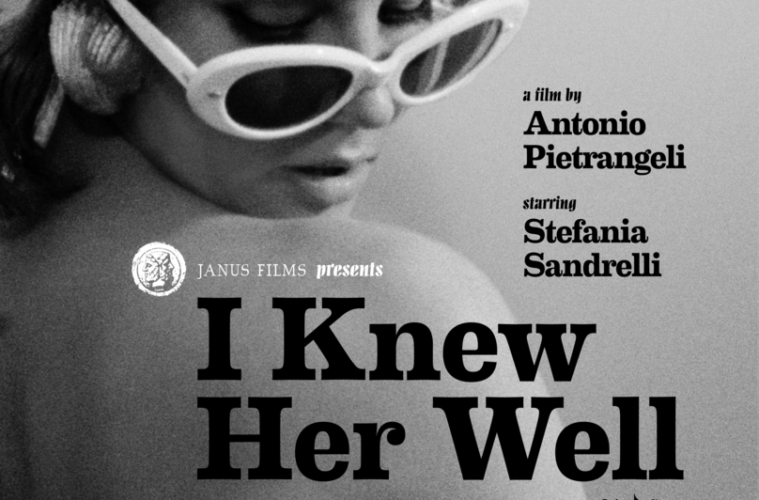

For one reason or another, Antonio Pietrangeli never took off internationally like his compatriots Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini. Part of that is certainly due to his premature death in 1968, when he drowned while working on a film. But even before that, I Knew Her Well, now newly restored by Janus Films and the Criterion Collection, was never released in the United States. It stars Stefania Sandrelli, who certainly has the makings of a star — five years later, she would help propel The Conformist to international acclaim — and Pietrangeli’s episodic structure, use of pop music, and jarring editing fits with the work of contemporary French New Wavers, and also bore a resemblance to Fellini, particularly La Dolce Vita; even in context of its time, it hardly seems uncommercial.

Is it perhaps because I Knew Her Well is genuinely and truly about a woman? And not just any woman (Red Desert had found its niche), but one who is out-of-time with her cavalier attitude regarding casual sex, yet firmly principled in all other walks of life? Maybe distributors thought that, without any recognizable names, the film wouldn’t have legs to stand on, or maybe the market for films such as this was saturated. Trying to say with anything close to certainty is a research project unto itself.

Whatever the case, Pietrangeli is acutely aware that for a film about a woman like Adriana (Sandrelli) to work, he needs to make her a star. Accordingly, the film begins with a camera finding her body on the beach and examining her, patiently, inch by inch, before she gets up. Holding her bra up, she runs down to the coast guard, asks him to fasten it, and goes on her way. She sings and dances and smirks, and the camera seems to be unable to look away for very long.

Adriana, fittingly, is an aspiring actress, and Sandrelli and Pietrangeli both go to great lengths to make her an appealing one. She is quick-witted and intelligent, but not “coquettish” (to continue with the Fellini comparisons) or ideal to the point of fantasy. In an early scene, she falls for a prank that her date plays on her and does not take kindly to the laughs of him and the pair accompanying them. At the same time, her attitude towards sex and work – she’ll have it without exchanging surnames first, but she won’t prostitute herself for riches in place of more fulfilling acting gigs – remain modern to today’s viewer. Her insight and direct manner never approach confrontation.

In addition to the aforementioned double date, which includes a memorable scene of the couples dancing to the car radio, we see Adriana meet a boxer, be questioned about one of her previous escapades, call out an author for solipsizing her in the name of his work, make movies, and dance. The film occasionally cuts abruptly to a brief flashback, as when a bottle of nail polish is knocked over; at other times, arrhythmic editing disorients the viewer, as with the final scene, or further disrupts time and context. (In one early scene that eventually finds Adriana in a moving theater, cuts occur invisibly, collapsing and reconfiguring the space around Adriana.) Scenes themselves tend to just start, leaving the viewer to ascertain the situation and read a new character without any advance clues, as if offering us glimpses into Adriana’s life, occasionally shattered by external disharmonies.

Played today, I Knew Her Well fits firmly into an established subset of arthouse films, but its lack of a narrative that exists in anything more than outline form only emphasizes the femininity of its social discourse. That is not to say that I Knew Her Well is didactic. On the contrary, not all episodes are heavily gendered, and the aforementioned, generalized story lends the film not an archetypal, insipid, or direct set of values and principles, but rather amounts to glances and pieces of a puzzle for the viewer to assemble. There are no decisive speeches and no heavy-handed plot events. It’s title comes off as something of a misnomer, the errant judgment of one of the many men appropriating or, as is the case in one key scene, chopping up and reconfiguring her image for their purposes.

Whether or not Pietrangeli is himself one of those men, treating Sandrelli with the same condescension or solipsism with which his film’s characters treat Adriana, is a question that is bound to arise when the discussion goes on long enough, and it is one worth having. But as some cuts privilege us to her inner memories while others attempt to prevent us from even understanding a scenario fully, Pietrangeli seems mostly aware of this pitfall. He privileges Adriana’s point of view in particular moments while denying us, through his structure and ellipses, the ability to really understand her. His film may sag in some spots, but his intentions do not, and, in that regard, amidst discussions of diversity and storytelling rights that are more amplified than any we’ve seen in quite some time, I Knew Her Well’s rediscovery could not be more provocatively timed.

I Knew Her Well is currently screening at New York’s Film Forum and will be released by Criterion on February 23rd.