One of the major revolutionaries of the 60’s pop art movement, a widely influential theorist, and a beguiling, colorful personality in his own right, David Hockney is a prime figure for a documentary, but Randall Wright’s portrait, Hockney, never makes a strong enough argument for its own existence. Curating archival home video footage, interviews from colleagues, and conversations with the own monolithic artist, Hockney is equipped with the necessary resources, but none of the unified focus that’s required to make the nearly two-hour documentary feel essential.

Already the subject of multiple docs going as far back as Brian De Palma’s early short, The Responsive Eye, Wright’s own 2003 doc, David Hockney: Secret Knowledge, and the 70’s pseudo-biopic, A Bigger Splash, Hockney isn’t a stranger to cinematic representation. As recently as last year, he stole the scene with his vivid turn of phrases in Tim’s Vermeer as the co-originator of the Hockney-Falco Thesis, and as a consultant on Tim Jenison’s ongoing attempts to digitally re-create art.

Just as Jenison re-oriented conventional notions about the laborious process of creating art, Hockney offers a comparatively mechanical and emotional view into an artist’s perspective. Wright has an obvious love for both Hockney’s spatially perverted body of work, and his frank persona, but there’s no sense of structure beyond chronology.

The chronological approach isn’t inherently bad – though it’s generally dull – but it’s harmful to the flow when Wright has also cultivated a rigid rhythm. Especially in the early-going as the documentary is fumbling for a voice, there’s a distracting stickiness to the way B-roll is placed in between interviews. Whether it’s stock footage that feels obligatory paired with the vibrancy of the stories being told, or a reluctance to simply watch a person speak, there’s a recurring sense of discomfort to the rhythms of the story.

Beginning expectedly with Hockney’s adolescence during wartime in the late 30’s, Wright struggles from the outset in finding a way to intersect Hockney’s childhood with his later art. There’s individual nuggets like his description of going to the cinema at an early age, and how the frames of the screen suggested the infinite, and another world away from his meager life, but they’re surrounded by material that fails to distinguish what made Hockney special.

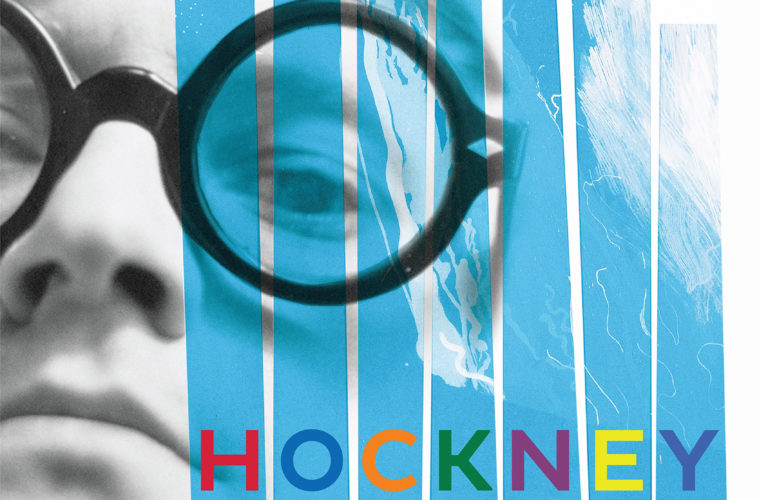

Moving away from rote early biographical details, Wright clasps onto something more prosaic in Hockney’s life-long passion for Los Angeles, which delves into the paradoxical glammed/damned nature of the city, and Hockney’s own accompanying rebirth into a brilliant blond, bottle rimmed, queer icon. Like Hockney’s art, which draws out a surrealistic present through its visions of smudged nostalgia and flamboyance of color, the material with 60’s-era Los Angeles feels like the most essential lens for understanding, or at least contextualizing Hockney’s output at the time. Far from the “unexamined pastiche” label that sometimes follows the pop art movement, Hockney’s work is presented as something immediately personal in its evocations of sexual transition and fears about rejection and freedom.

Over trilling saxophone runs and a surrounding ecosystem of likeminded individuals, the movie finally finds a synthesis between the fraught art with its scribbled pastels and direct/indirect evocations of struggling with homosexuality, and personifies perfectly why Hockney was such a vital figure. But Hockney, for the most part, is either tediously predictable or jumbled in following Hockney’s life.

That’s even more a shame when Hockney’s art is so confrontational to the usual modes of understanding space and pigmentation in the first place. With their geometric alienation and staccato application of color, the longing shots examining Hockney’s art adds well-needed personality to a documentary that is constantly staid and drab.

Hockney was above all, a shifty trickster in his approach to art, refusing to let typical conceptions of gravity or visual construction cloud his 2D-adjacent view of the world. Moving through some of Hockney’s most famous pieces from the Blue Guitar Series to A Bigger Splash, the documentary contributes valuable insights like his belief that space was an illusion and a strong sense of theory, but it’s repeatedly hard to shake the notion about why this is a movie rather than a television show.

By the end, Hockney’s life has been drawn in broad strokes, but it’s clear that certain events should have been the focus as each of the eras in his life yields their own specific vision of art. There’s no doubt Hockney deserves appreciation for his artistic influence, but this documentary is less a reflection of his singular presence than the result of haphazardly mashing together a fascinating life.

Hockney is now in limited release.