While watching War Horse, the Steven Spielberg picture whose trench warfare sequences evoked the great Stanley Kubrick film Paths of Glory, I was reminded of a quote from Martin Scorsese that fits War Horse and rings incredibly true with Stephen Daldry‘s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Scorsese discusses the ending of the Kubrick film in a documentary about the man, A Life In Pictures, and described how deftly he brought home the emotional ending.

“There’s a tendency when you get to that level of emotion, or that level of sentiment. Not sentimental, not sentimentality, but sentiment. Just portray this aspect of humanity. Very often, you know, you fall into sentimentality. You really do. And it’s very very hard, very hard to pull off.”

I’m sure Mr. Daldry would agree.

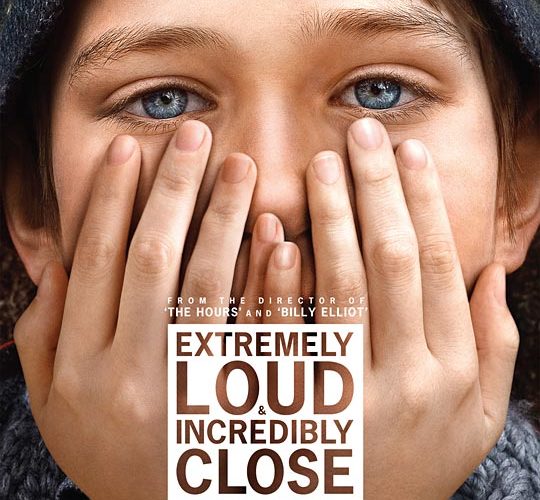

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close tells a story that its director believes is both unique and general. It is in this mix that critical problems arise. Newcomer Thomas Horn capably plays Oskar Schell, a brilliant, precocious boy who hovers somewhere around Asperger’s Syndrome (tests are inconclusive). His father, Thomas, (Tom Hanks, as charming and lovable as humanly possible) perishes, leaving the boy behind with his mother (Sandra Bullock) to cope with the loss. But he also leaves the boy with an unfinished mission. Dad would concoct these very intricate games in order to get his son to explore the world in the physical the way he devoured information so thoroughly in the theoretical.

Thomas passes away in the middle of Oskar’s search for the sixth borough of New York City. To complicate things further, a year after Thomas’ passing, Oskar rummages through his father’s untouched closet and smashes a blue vase. Contained inside is an old key which, presumably, opens a lock. The only clue is listed on the small vanilla envelope that conceals it, the word “Black.” A color, sure, but maybe a name? The resemblance to one of the his father’s ingenious puzzles sets Oskar off on a search to find every listed Black in the phone book to try and find something–anything–that could connect him to the man has lost. This experience forces Oskar to overcome his fears and genuinely connect with others in a way that was not possible when Thomas himself was there as a safety net.

And if that was it, this could be a fine film. Indeed, there are very sweet moments contained within, such as his compaionship with a mute older man (a brilliant Max von Sydow) who tries to nurture the boy along his feckless journey and show him that maybe it is more important than the destination. Or when his mother Linda’s excessively lax parenting is actually paid off in a plot contrivance that ends up being as emotionally gratifying as it is practically infuriating. Regardless, I teared up as they recounted their favorite moments with the man they lost.

But in the end, all of this is rendered meaningless because it is “the 9/11 movie,” a title that is well-earned.

Don’t believe the disingenuous advertising which expresses this is not as a film about 9/11, but about “every day after.” That’s akin to Schindler’s List not being about the Holocaust, but “how Jewish people dealt with it.” Extremely Loud is packed to the brim with 9/11 imagery, taking its time to even stop its subjective view from Oskar’s eyes (bleary-eyed focuses on items that scare him, loud and kicked up sound design to show how everything affects his senses more, and a relentless voice over) to give a five-minute aside where Sandra Bullock can cry in pain as she talks to her husband on the 105th floor, watching from the most gorgeous panoramic view of the Twin Towers as they burn towards their inevitable collapse. Notice how the smoke billowing fills the frame just so.

This is where sentiment and sentimentality are forever crossed, dooming this film to justifiably correct calls of co-opting a national tragedy to move an audience. You will once again be shown the news footage that is already burned into most of its viewers memory. You will hear the boy say on numerous occasions “my dad died on 9/11” as a stranger can only muster up an “I’m sorry” in response. You will see close-up images, in pristine prints, of bodies falling from the towers. And, most gallingly, you will track Tom Hanks digitally falling from the towers, from the opening credits until about the second act break. Then we see his face, body akimbo behind him, just before he meets the concrete and, thusly, his maker.

And I sit, thinking about my uncle who managed to get out from the high perch of the 65th floor, who has never recounted his experience with anyone. I think about the unfortunate people who actually lost family and friends in a similar way to the fictional Thomas, the very people who might be smudges on those photographs used as a prop. And I think about why this is at all necessary. Near the end of the film, Linda mentions how all the people that Oskar met (shown mostly shown through montage, as if that wasn’t the driving force of the film or anything) have lost someone in their lives, a powerful truth that makes all the 9/11 imagery even more galling.

I’m not sure who it is to blame for shoehorning all of this needless pain and anguish on the audience. I have not read Jonathan Safran Foer‘s novel of the same name, and I find it hard to believe that Eric Roth, a man whose deft hand crafted so many small, personal moments in the criminally underrated The Curious Case of Benjamin Button could have gone this far off the reservation. This doesn’t need to be a story about 9/11, or any day after. This is a story about a boy, disconnected with the world accept for the special bond he shares with his father, his confidant, his hero. It’s the story of how a mother has to deal with a distant, grieving child while struggling to also be a widow whenever she can make the time.

The title is extremely apt. It is incredibly close to a gripping, emotional story that we can all connect with. Instead, we are screamed at, bombarded with SADNESS that will AFFECT US in a way that would not be possible without evoking SEPTEMBER 11TH. On second thought, maybe “sentimental” is too kind. “Needlessly exploitive” seems right on the money.

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is now in wide release.