The bracing tension of Rob Connelly’s Edge of Winter hinges on a powerful portrait of a father who compulsively believes his self-worth to be inextricably bound to his sons. As the film unfolds, this man’s expressions of “love” for his children begin to metamorphose in unsettling then monstrous ways, resulting in a descent into madness reminiscent of The Shining in the way the ostensibly unassailable fiber of familial love is threatened by violent insanity in the patriarch. Kubrick’s film found horror in the darkest reaches of the creative mind, but in some ways, the psychological source of terror in Edge of Winter is scarier because it channels the more universally experienced phenomenon of the bond between parent and child. Though fundamentally a beautiful thing, this bond can turn poisonous in cases where parents tie their identities too much to their kids and grow possessive as a result. Connelly’s film takes this familiar distortion of parental love to its logical extreme and is compelling because of it, for the most unnerving horrors are those that hit closest to home.

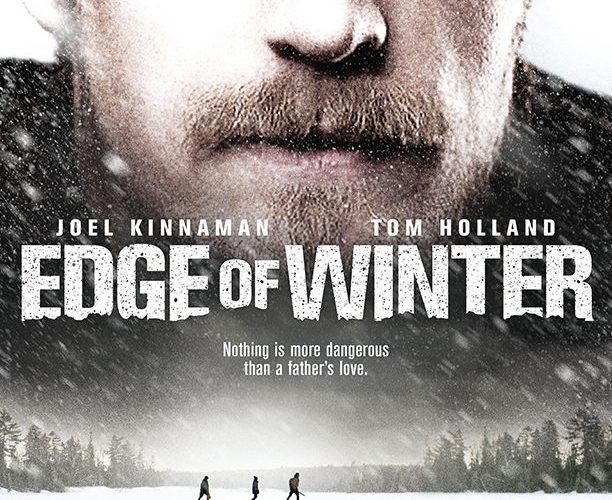

The film begins in the home of Elliot Baker (Joel Kinnaman), a divorced father who is given the chance to hang out with his two boys (Tom Holland and Percy Hynes White) for a few days. With a concision verging on cinematic shorthand, the dialogue in the film’s opening scene makes it a point to emphasize Elliot’s failed status as father and financial provider, planting a motive for the increasingly possessive behavior he will later demonstrate toward his children, who are his only remaining source of pride in this world. With similar succinctness, subsequent moments in the scene articulate emotional distance between father and sons through the awkwardness of their conversation, whereas Elliot’s unexpectedly vicious outburst over the boys’ tinkering with his hunting rifle introduces both the father’s temper and the firearm, which the law of Chekhov’s gun dictates must come into play by the film’s end. We wonder whether the firing of one will relate to that of the other.

The rest of Edge of Winter follows the trio as they venture into the backwoods wilderness and end up stranded in a cabin amid a blizzard. Like its opening scene, Connelly’s film as a whole excels at being streamlined and highly controlled without feeling overtly constructed. Characters’ actions seem to arise organically from personality traits that had earlier been established, whereas twists in plot-level circumstance feel like plausible emulations of nature’s vicissitude. The film’s greatest feat of orchestrated realism, however, lies in the characterization of Elliot, the effectiveness of which stems from the incremental onset of menace rather than a sudden shift from man to monster. The dad’s rage over the gun is the first major red flag, but the tension of that moment recedes quickly—though not completely—with an apology and an offer to teach his boys how to fire a gun (plus, a father panicking over his children handling a deadly weapon is hardly unreasonable). Things seem largely okay until we learn that the father’s sprained wrist—which had been casually introduced in the opening scene—had resulted from a violent altercation with his former boss. Another red flag. When Elliot steals a peak at his son Bradley’s phone and discovers that the boy had texted a friend about him in a derisive fashion, he confiscates the phone and exacts revenge by deliberately withholding information about how to shoot a rifle, resulting in Bradley hurting his shoulder. Alarms are going off at this point in reaction to Elliot’s disturbing petty-mindedness, and yet the film continues to tease the possibility that Elliot is acting out of love, albeit a poorly communicated version of it.

The subtle and gradual way with which the film portrays Elliot’s psychological unravelling generates tremendous suspense by convincingly showing how an initially normal-seeming guy can come to fully inhabit the role of villain. The subsequent, frightening implication is that we are all only a few misfortunes and emotional breakdowns away from being a danger to those around us. For Elliot, his undoing flaw is his deep-seated emotional insecurity, which Kinnaman brings out in an exquisitely nuanced performance. Through an off-putting combination of vulnerability and aggression, Kinnaman imbues his character with a violent volatility that turns even the most outwardly benign scenes into ticking time bombs that can go off at any moment. Arguably even more unsettling is the degree to which Elliot remains a sympathetic character despite his increasingly unnerving behavior. His frustration over his financial and familial situation and his intense desire to be with his children are relatable, and he expresses his feelings sincerely rather than with calculated duplicity. When things go south, we experience the acute emotional discomfort that results from seeing a character not so different from us become corrupted in ways to which we assumed we were immune.

In the end, Edge of Winter’s vision of madness peters out rather than swells, with the very final shots revealing that the film’s commitment to efficiency has occurred at the cost of poetry. Where The Shining was vast and unruly, Connelly’s film is marked by leanness, which is effective for communicating the inexorability of Elliot’s psychological breakdown but hinders the realization of the creative potential supplied by the film’s provocative premise. Still, as a powerfully acted exercise in suspense and a hair-raising depiction of parental love gone wrong, Edge of Winter is nothing short of magnetic.

Edge of Winter is now in limited release and available on VOD.