I’ve been lucky to have never used painkillers whether as a result of high pain tolerance or simply not having experienced enough to deem it necessary. I know people who have, though, and it is a godsend at times whether opium-based or not. So I couldn’t blindly say Oxycontin and Dilaudid should be outlawed. Morphine has always seemed so commonplace that any prescription drug compared to it has brought along a stigma of “good” rather than “bad” for me despite heroin also being a close sibling. It therefore took be by surprise when the whole opioid scare began to cultivate insane fears on behalf of patient and doctor alike. Can you truly call an effective drug dangerous just because a few bad apples abuse it?

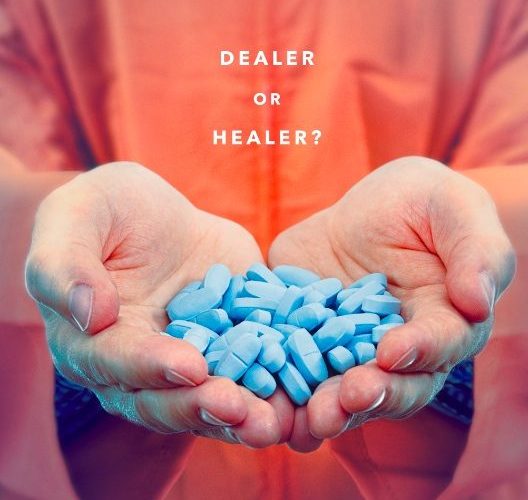

This is the question that Eve Marson‘s documentary Dr. Feelgood: Dealer or Healer? asks by focusing on one man who almost lost everything during the government crackdown on prescription narcotics, Dr. William Hurwitz. But don’t expect an answer as none can be provided. Just like how chronic pain cannot be measured, the rights and wrongs of Hurwitz’s case merely open up the conversation rather than provide it closure. When opioids were deemed legal, he did what he believed he should as a doctor focused on dealing with pain. And he has numerous patients who hail him as a hero for getting their lives back on track. But there are also those he touched that lost theirs. The blame for that isn’t easily decided.

I admittedly believed from the way things had begun to progress that Marson had set out to prove Hurwitz deserved none of it. We meet his daughter and a patient all saying nice things. We meet Hurwitz himself now released with a smile on his face to speak on how he wouldn’t have been a good doctor if he let his patients live with their pain when he had an answer. A study is even presented to corroborate his practice of prescribing as many pills as necessary on a patient-by-patient basis. Someone comes to Hurwitz, he gauges how much medication they can handle, and then doubles the dose when they become tolerant. There should be no risk of over-dose if they use it correctly. And that’s ultimately their choice.

Suddenly, however, subjects onscreen change. We meet a man who tells his tale of Hurwitz helping him deal with his troubles before eventually explaining how he abused the relationship. We meet the spouses of patients who filled his prescriptions only to become addicted to the point of no longer being able to control their withdrawal or stay afloat. So it’s hard not to vilify Hurwitz when he should have been able to see what was happening. Naiveté is not an excuse when things are falling apart around you. Whether or not he willfully allowed his patients to misuse their pills — to deal them on the streets — becomes inconsequential on a level of morality. He could have done something to stop them. His hands are far from clean.

So Marson puts the onus on her audience to look below the surface at the complexities of the case and the drug itself. You must acknowledge the statistics and Big Pharma pushing doctors to start using opioids in less severe cases, flooding the market in the process. Hurwitz was naïve enough to believe that the “problem” patients risking his freedom and theirs still needed help. Whether this is true or not is up to the person soliciting help. Maybe Patient A wasn’t experiencing pain as harshly as he/she thought. Maybe Patient B had an addictive personality and would have been hooked on lesser doses anyway. Maybe Patient C lied. There are so many variables, but none more important than those who needed high doses and used them properly.

You can demonize Hurwitz or hail him as a saint — controversially unorthodox doctors have dealt with that scrutiny for centuries over multiple issues. But where does media sensationalism come in? What about the black and white objectivity of local police and FBI agents refusing to see anything other than the tragedy? It was public perception that outlawed opioids in the first place, put them back on the market, and now handcuffs physicians into worrying about their own lives above their patients. This isn’t a drug problem or even one about ego. It’s about greed, poverty, and abuse. Pharmaceutical companies want profit, doctors want to help, and this dynamic’s economics distort in ugly ways. Hurwitz was the victim of a witch-hunt, but not wholly without cause.

Credit is due to Marson for staying objective in how she tells Hurwitz’s story so it can transcend his individual experience within this complicated landscape. She talks to people who love him, hate him, and even some who have forgiven him if only to move on. She makes sure to leave in two short passages that reveal how Hurwitz was in the room when his ex-wife and daughter are speaking too. Marson could have left those out and made us believe everything was said without the potential for emotional coercion, but she chose to put it all out into the open instead. This means her account isn’t quite definitive as far as his story goes, but that’s okay. She’s merely presenting an entrance into the problem — how it’s interpreted is up to you.

Dr. Feelgood: Dealer or Healer? has a week-long theatrical engagement at Cinema Village in New York starting Friday, December 30th before hitting digital platforms January 31st, 2017.