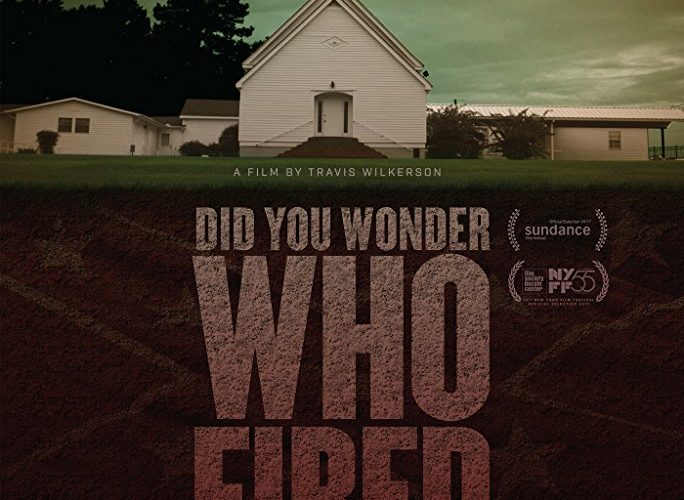

Throughout the remarkable Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? – director Travis Wilkerson’s attempt to learn more about and confront the murder of the African American Bill Spann by his white great-grandfather, S.E. Branch, through a cinematic essay on racism in America – there are many black-and-white images of houses, forests, and roads in Alabama, the state in which the killing took place. As interview subjects recount memories or details related to the crime — through either first-person testimony or Wilkerson’s second-hand paraphrasing — the film often eschews focusing on the speaker to dwell on local spaces, quietly moving through static shots of Alabaman milieus. These images are so still that, at first, they resemble photographs — specifically, old photographs of the sort that one might find in the photo album of someone who was alive when Bill Spann was killed. But if you look closely, you’ll see that the leaves and grass are actually moving, rustling ever so slightly in the breeze.

These shots are some of the film’s most important because they articulate, embody, and realize one of the film’s central projects. In having filmic shots appear like old photographs to the point where the viewer’s impression will almost always be one of seeing a still image come to life (provided they notice the movement at all), Wilkerson signals that his film will be about reanimating the dead, about exhuming a past that a society built on racism and oppression has tried to ignore or forget. On the other hand, the fact that the images themselves were never actually still to begin with — they only appeared to be — suggests that the past itself never died, or, alternatively, that we’ve never moved beyond that which we thought we’d left behind.

The latter pertains especially to moments when Wilkerson recounts how his car was tailed on multiple occasions during filming; to his description of the Confederate memorial at which he tried to find his white nationalist aunt; and to the moment when it is revealed that one of his interview subjects, a black woman, insisted that her identity be kept confidential, with the implication being that she feared the information she divulged would make her a target for racist violence. All these incidents evoke segregation-era America, except they occurred within the last five years. Many of us want to believe that, in our post-Civil Rights era, post-Obama world, racism is a relic of Old America, but the Trump presidency and the attendant upsurge in white supremacist shows of power indicate that we are far from where we need to be. It is into this broken reality that Wilkerson’s film speaks.

When the repressed past gains sudden and violent visibility in the present, the genre that’s evoked is horror, and one of the film’s greatest strengths is the way it leans into this association. In laying characters’ voiced-over accounts of past events over present-day images of the houses and stores in which these events took place, the film conjures the specter of history in contemporary spaces that might otherwise have appeared nondescript. This strategy of juxtaposing a narrated past of horror and trauma with a visualized present brings to mind Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog and Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson, and, like those films, imbues certain scenes with the feel of a ghost story. The word “haunted” is used at least twice, by Wilkerson vis-à-vis a convenience store and by a witness about a hospital (via Wilkerson’s secondhand account). In regards to the bar in which Spann was murdered, the director asks, “Have you ever been in a place that feels like something terrible happened there?,” lending past tragedy the present-tense weight of a phantom whose presence can be felt.

In this scene at the bar, there is a brilliant moment in which the deathly stillness of the image — the indoor setting means that there is no wind to animate details of the shot — is interrupted only by a TV flickering eerily in the background. This slight movement, combined with the knowledge of the space’s violent history and the uncanny sight of a bar completely devoid of people, generates a palpable unease that feels culled from David Lynch’s oeuvre. In fact, a Lynchian influence is evident throughout, from long shots of winding roads to disturbingly tacky, unnaturalistic visual effects to a showstopping moment when a clip of Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit” — spliced into an image of trees in a place tellingly dubbed the “Klan Town” — is played in reverse, evoking the speech pattern of Twin Peaks’ Black Lodge residents. As many have noted, Lynch has a demonstrated interest in deconstructing myths that America has about itself (in The Return, he mines the moral and metaphysical fallout of America’s other historic act of unspeakable violence, the dropping of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki), so such references to his work are fitting and, especially when expository voiceover commentary gives way to disturbing suggestion and devastating sensation, terribly effective.

Indeed, there are points where Wilkerson’s narration seems to get in the way of the film’s more fascinating ambitions, such as when he describes Selma as being, in contrast to the Confederate memorial from which he’d just left, a place “where blacks have their voice.” While there’s no issue with the content of what he says, the triteness and vaguely slogan-like quality of the phrase clashes with the ethos of the film’s visual organization, which evince a more vexed and nuanced engagement with realities that exceed language’s capacity to represent. And yet neither is this phrase entirely condemnable when its invocation of voice is central to the film’s project. Throughout, Wilkerson punctuates his visual / aural exploration of place and history with calls to “Say His Name” or “Say Her Name,” the pronouns referring to black victims of racist violence. Eric Garner. Trayvon Martin. Sean Bell. Freddie Gray. Aiyana Jones. Sandra Bland. And, eventually, Bill Spann. In a film that is about simultaneously recognizing the ways in which the wicked past persists and escaping its hold, these namings function like incantations, an attempt to both immortalize the lives that have been lost and banish America’s demons to the grave.

Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? opens on February 28 at Film Forum and will expand in the coming weeks.