In much the same way J.R. Hughto’s characters interact with one another in made-up dialogue with fictitious personas used to record “rehearsal” conversations or stock situations, the film they inhabit—Diamond on Vinyl—appears to have been built in much the same way itself. Hughto populates his story with a trio of captivating creatures, each stuck inside him/herself with desperation to grow. It’s as though he’s drawn them three-dimensionally before placing them inside of his story, allowing them to act in a more genuine, authentic way when brought to life. Their peculiarities aren’t therefore a byproduct of the screenwriter attempting to be witty or smart, but rather intrinsic qualities they’ve possessed both before the cameras rolled on Henry (Brian McGuire) and Beth’s (Nina Millin) intimate engagement night and after their journey here reaches completion.

As a result, there’s much more happening onscreen than the synopsis may reveal. While beginning with Henry’s admittance of possibly not being in love with Beth getting exposed courtesy of his tape-recorded trial-run proposal found on the same device she just discovered documented their lovemaking hours before, this is only the catalyst to split them apart for the film’s duration. She tells him to take his stuff from their home and think about whether he’s serious about wanting to get married before coming back. This devastating reversal from joy to betrayal overtakes her with emotion so that a stranger knocks on her car window to check that everything is okay. But while Charlie (Sonja Kinski) does generously provide comfort, she also can’t help from becoming infatuated with discovering exactly what’s caused Beth such pain.

It’s this young woman’s entry into their lives from who knows where that sets into motion the falling dominos to end in either a rekindling of love or the destruction of what little connection still remained. Charlie does inject herself into Henry’s space to become a sort of sounding board he can use to work out exactly what he’ll need to say to win Beth back, but it’s not an act of selfless charity. She is perplexed by his eccentricity—a voyeuristic nature to aurally record voices like she visually captures faces with her camera and his strange relationship with a vintage record of banal conversations between a husband and wife to ward off thieves from entering your house when away called Safe & Sound—yearning to understand its intricacies and their inexplicable hold on her.

In order to do so, Hughto puts them into a series of circumstances that should seem awkwardly uncomfortable to any “normal” person with a distinct mistrust of strangers and their motives. Not only does Henry let Charlie into the hotel room his finance just exited, but he also accepts her invitation to stop by again to join him in recording one of his improvised situations. Beth in turn opens her door for the stranger later on because of the aforementioned randomly shared moment and the girl’s self-revealed (and creepy) desire to see them get back together. Charlie on-the-other-hand blindly accepts Henry’s introverted, stalker-like habits devoid of fear thanks to his disarming “guy next door” persona. Thusly, Diamond on Vinyl can’t help but conjure ideas of serial killer territory while somehow appearing believable in context with the characters involved.

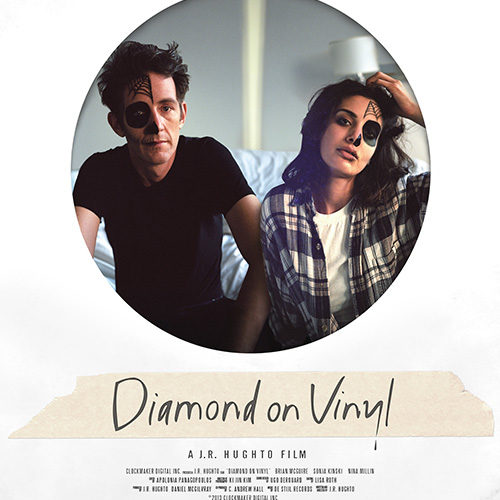

It’s a testament to the screenwriter’s ability to create such wholly unique people both entrenched in their own insecurities as well as each other’s when willing to open up. Hughto gives us these two sides for each of our central three, transforming his film into one of the Day of the Dead Calaveras we see in the poster and painted on Charlie’s first model courtesy of roommate and confidant Kate (Jessica Golden). Their proclivities are introduced as oddities on the surface before dissolving into mere personality ticks that are much more innocuous than our minds had believed. Henry, Beth, and Charlie each contain this conflict of beauty and danger they cannot quite reconcile until pushed beyond their boundaries so as to finally discover what it is they want beneath societal pressures and self-doubt.

So when it appears Charlie is making a move on Henry, it isn’t necessarily to be with him as much as it is to feel something as strongly as Beth obviously did/does. Henry’s candor with Charlie and enthusiasm towards her willingness to play-act isn’t because he wants her to replace the woman he may or may not love, but instead to practice exposing his emotions without the risk of never having a second chance. But while they start with recorded voices, an escalation in action makes their roles almost inseparable from reality until a decision must be made. Has Henry fallen for Charlie? Is her “game” of being anyone but herself burying her identity or setting it free? Can admitting it aloud to an outsider cure Beth and Henry’s unspoken pain?

The film and its performances show us how fantasies are simply that—and oftentimes less enjoyable. McGuire embodies Henry as a man unable to accept spontaneity or the truth if it doesn’t coincide with the carefully rehearsed plans he has already approved himself to make and Kinski portrays Charlie as a woman identical in the opposite way with her inability to stop and build a life outside of the adventures her curiosity draws her towards. They are contrasting halves who need the other’s crippling neuroses and gregarious experimentation respectively to discover who they really are. He wants to be what he believes his “perfect” idol (Jeff Doucette’s George) is while she a fearless extrovert whose vulnerability is repressed in lieu of complete self-assured passion devoid of consequence.

Their self-discoveries are shown via the same voyeuristic tools on display with the present moment’s audio cutting out into a lo-fi recording—sometimes replayed with the wrong voice—and electronic archives played as both imaginative flashbacks or re-envisioned recreations with different participants. Which part is the beauty of illustrious skin or the danger of the darkly painted recesses of hollow bone beneath could be disputed, but each character’s final outcry of emotion can only be real. Love is found where it was lost, trust where it was betrayed, and fear of the unknown where the steely cold façade of strength once presided impenetrable. While we may not record strangers or blatantly invade people’s privacy in our day-to-day, we still all glean answers for how to cope, grow, and engage the world around us so we may find ourselves.

Diamond on Vinyl is now on VOD via iTunes and receiving a limited engagement in NYC (12/7), Boston (12/8), and LA (12/10).