The story is older than Shakespeare: two star-crossed lovers attempt to make things work despite a family’s best (worst) efforts. The difference here, as Hollywood would have you believe, is that this is radical when placed in a new context. Like Love, Simon earlier this year, Crazy Rich Asians’ place in the contemporary culture is predicated entirely on its status as the first film from a major Hollywood studio in twenty-five years to have Asian-Americans as the leads. Such a statistic says much, much more about the state of American commercial cinema than it necessarily does about the film, but any assessment must take this into account.

As a movie that has positioned itself as the first in a hypothetical wave of representation, Crazy Rich Asians is blatantly diminished by its status. Such a burden is too much for almost any movie, especially one as intellectually, aesthetically, and sociologically featherweight as this, but its flaws are magnified in the face of its goals. All of the features that feel clumsy at best — all of the moments that border on insensitivity — gain a corrosive power because the product as a whole has been tailor-made to serve this present moment, targeting an audience that may accept something that seems so evidently substandard (judging from a very low standard indeed) simply because there appears to be no alternative.

I should note that, as an Asian-American — specifically Taiwanese-American (and thus do not claim to speak for all Asian-Americans) — there is something of a tiny thrill when seeing Mandarin spoken in a familiar context. Unfortunately, almost everything with which Crazy Rich Asians concerns itself is rendered unfamiliar or alien by virtue of its perspective which — despite the involvement of a largely Asian creative team, including Chinese-American director Jon M. Chu, Malaysian co-screenwriter Adele Lim, Singaporean source novel writer Kevin Kwan, and the cast at large — feels more-or-less indistinguishable from reams of Hollywood product of the past decade. This is an American film through and through, one that, due to what it is depicting, delves into frankly repulsive and shortsighted territory.

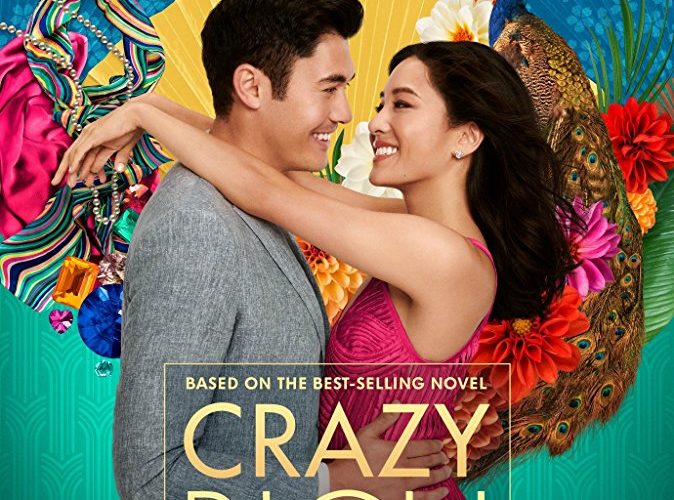

One of the main problems is reflected in the second word of its title. Crazy Rich Asians, a film that luxuriates in decadence, claims to cast a critical eye on the old-money wealth of the Young family — the expansive Singaporean enclave that main character Rachel Chu (Constance Wu) is placed in unwitting opposition with — yet takes every single moment to delight in the extravagance on display. Whether it be the enormous wealth of the Youngs — the heir, Nick (Henry Golding), is deeply in love with Rachel in spite of the heavy, cruel disapproval of the family, especially mother Eleanor (Michelle Yeoh) — or simply the still-immensely comfortable living of the family of Peik Lin (Awkwafina) — which, as the movie takes great pains to demonstrate, is supposedly self-effacing or tasteless enough to be funny and therefore acceptable — the film finds itself breathless in its pursuit of the next speeding drone shot, the next opportunity to ogle the supposedly easy living of Singapore. Even a night market scene, one of the few sequences that seems to have something approaching a soul, is wrapped up and summarily forgotten so quickly that it feels like a deliberate act of misdirection.

Crazy Rich Asians otherwise has no time or inclination to explore anything traditional in Asian culture unless it is explicitly related to the plot in a way intended to draw out the nigh-villainous qualities of the Youngs. The movie’s most fundamental and detrimental demerit is its frequent flattening of characters and centuries-old practices into one-dimensional stereotypes, conflating so many different attributes so as to create something muddled and more than a little offensive.

Tradition is inherently connected with wealth in a shotgun marriage set in deliberate opposition to Rachel’s modernity as an NYU professor of game theory (which, of course, does come into play at the film’s climax, in an utterly egregious and predictable deployment of a rundown mahjong den). As embodied in the ironclad dichotomy of Crazy Rich Asians, there is no choosing both love and tradition — latter is seemingly so duty-bound in the film’s vision, so unyielding, that only through a complete break can personal happiness be achieved. Everyone in favor of tradition is revealed to be a martinet — even the kindly grandmother (Lisa Lu) — and despite some attempts to add depth (aided by Yeoh’s strong efforts), none of them come across as anything but thoroughly pragmatic.

Of course, the idea of a parent being unreasonably hostile to a child’s partner is nothing new in Hollywood film. But that very reason is why the use of an Asian culture — and pointedly an exotic Asian setting outside of America, held conveniently at a distance — feels like little more than window dressing. Asian signifiers are used almost as a form of Othering, setting apart the American-raised Rachel at every juncture from her potential in-laws. Nowhere is this more apparent than in a scene of dumpling-making where Rachel has to be taught the method. In dialogue, Eleanor explicitly connects this storied task with the labor of love that she gave throughout Nick’s childhood, something that would be perfectly valid (as seen in, to name just one example, Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart) if it was not so immediately and obviously used to denigrate Rachel’s station in life.

Yet Crazy Rich Asians obstinately refuses to abandon the trappings of the rich, and many characters are shown as positively indulging in these pleasures — pleasures that are explicitly modern and consumerist. From the requisite makeover that Rachel undergoes in order to show up Eleanor — a moment of self-actualizing through materialism — to the lavish wedding centerpiece, which features a church converted into a jungle, complete with drifting water that accompanies the bride’s procession, these are depicted in the most cloyingly fawning of ways, as if fairy tales could be achieved if only one had the right number of zeroes at the end of their bank account. There’s even a completely pointless, extensive subplot with Nick’s charity-fashion icon cousin, Astrid (Gemma Chan), who has to reckon with her husband’s attention-getting affair and which ends with her defiantly donning a pair of $1.2 million earrings, as if to suggest that rampant consumption is, in certain circumstances, the unequivocal moral high ground.

Numerous other (at best) tone-deaf moments abound, including one atrocious “comedic” beat involving the unspoken menace of the Young family estate’s Sikh guards, but the one that most sticks out in my head is the introduction of (Korean-American) Ken Jeong’s character, the father of Peik Lin. He is first introduced speaking English with a conspicuous Cantonese accent, something that would be utterly ordinary for someone living in Singapore. But then he drops the act, explaining his education at Cal State Fullerton to the laughter of Rachel and his family.

Such a moment would play as stereotypical but pointed if directed at a white figure. But in context, with Jeong’s character playing the joke on a fellow Asian-American, it comes off as bizarre, pointless, and so indicative of this film’s muddled and confused perspective on the milieu it attempts to depict. Which begs the question: who is this film for? Is it directed at Asian-Americans who, despite the vast gap in both wealth and living style, desire representation? Is it aimed at general American (read: white) audiences who can thus claim to be “helping out” and laugh at the sort of joke described above? Most disquietingly, there seems to be no definable answer.

At two separate moments, including the lavish wedding reception, Grace Chang’s “Wo Yao Ni De Ai” plays on the soundtrack, a choice that immediately reminded me of my own complex associations with my heritage. As someone who learned the value of understanding my native land and culture far too late, I came to know it, in one shape or another, through films from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Chang’s song also happens to play during Tsai Ming-liang’s The Hole, in which Yang Kuei-mei and Lee Kang-sheng lip sync and dance to the track. The two uses could not be more different in terms of impact: Tsai’s contains an actual sense of eroticism, longing, and exuberance; Chu’s conveys a nauseatingly slick emptiness. Why should Asian-Americans wait twenty-five years for this shallowness? Why shouldn’t they look to their homeland, flattened and hollowed out in this film, for a faithful, distinctive representation of Asian characters onscreen? Why should they settle for and embrace this?

Crazy Rich Asians is now in wide release.