The fallacy of escape is thinking it’s possible to truly leave the past behind. You can travel thousands of miles away and put years in between, but the stuff forcing you to do so never disappears. It marks you and shapes you whether you like or not, for better or worse. Ignoring to forget is just another way of letting it affect you because it remains the catalyst for where you are today. It caused you to pack up; it caused you to move forward without looking back no matter how difficult or scary doing so ultimately proved. We don’t know why Colby (Stephanie Brait) left home to travel the country as a drifter, hustling and lying her way into beds and money. We only know her pain.

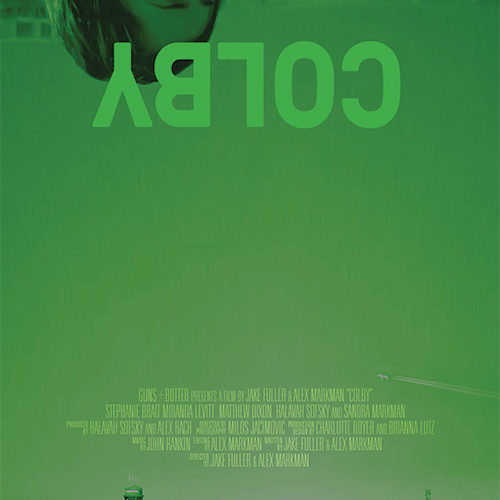

It’s this struggle within to be better than who her mind says she is — that person her mother refuses to talk to — that writer/directors Jake Fuller and Alex Markman put onscreen in their debut feature Colby. We see it hidden underneath her coy smile and ever-calculating brain shifting to and fro to find an angle. She embraces the person she doesn’t want to be because it helps her survive. That person is how she’s remained alive and happy (at least on the surface), so leaving her behind isn’t a choice she can make. Colby wishes it were, though. She wants to be done with this life, to return home and have another go — a realization that either means forgiving Mom or asking for forgiveness herself. But it’s time.

To do so is to spend one more adventure in the grey areas of immorality. To stay warm and fed until her mother calls her back means finding someone willing to help. So she picks up a stranger in Henry (Halavah Sofsky), craves his idea of squatting in an empty beachside estate, and basks in the freedom the sand and ocean provide without yet seeing the vast abyss of unknown existing beneath the aesthetic beauty. Unfortunately for Colby, the house isn’t empty for long. While she slept on the beach the owner George (Matthew Dixon) came back and found Henry in his bed. The police are called, his car is towed, and Colby’s possessions are locked in impound. With nowhere to go — home included — she must wait.

This begins the chain of events that continuously finds her staring up at the door of George’s home. First she returns with a con and then passive blackmail. But as soon as his wife (Sandra Markman‘s Sandi) and daughter (Miranda Levitt‘s Samantha) are introduced, we watch Colby’s cold manipulations turn into sadness and longing. She pretends to find the familial bond this family possesses as cute, but we know it’s exactly what she wishes she had growing up. No one knows if it would have changed things — again, we don’t know why she’s a four-hour airplane trip from Mom — but it’s hard not to imagine the possibilities. It’s even harder to ignore the effect she has on Samantha in bringing this young girl down to her level.

Brait’s Colby reveals a palpable sense of uncertainty and caution when around Samantha. She’s keen to make a friend without expecting anything in return, but she’s not quite stable enough to accept it once jealousy and ego enter the equation. It’s difficult to therefore empathize with the character knowing she’s aware of the impact she’s making. If Colby were to acknowledge the potential suffering letting Samantha imprint on her provides by pushing her away with tough love, we could find redemption. But bluntly saying “No” without meaning it, forgetting this girl isn’t world-wary like her to see between the lines of a seemingly fun situation masking danger, only shows how Colby may be too far-gone. Her guilt isn’t enough to prevent her complicity.

Because of this Fuller and Markman’s film is a divisive experience wherein those refusing to look beneath the façade at the true purpose of their story will get angry. These are the people you could infer are like Colby’s mother — unyielding to the image in their heads and preconceived notions of who she is. They can’t see the goodness in Colby because it’s near impossible to do so. Those glimpses of heartfelt pain and second-guessing are fleeting, but we wonder if she’s as bad as those she has hurt believe nonetheless. Does she deserve an opportunity to prove them all wrong? Yes. To the filmmakers’ credit, however, this isn’t that opportunity. This is rock bottom, her accepting loneliness and discovering it’s on her alone to be better now.

The film does a wonderful job showing this progression if only by ensuring Colby’s decisions aren’t so easily made anymore. Even though her pausing to look at the situation she’s in from the perspective of those who might get hurt in order for her to exit unscathed is half-hearted, the fact she pauses at all is progress. Where she ends up is a touching place of catharsis, experiencing what she’s craved her whole life despite accidentally via one more lie. The scene asks more questions than it answers (Where’s Samantha and should we be worried?), but it delivers on the evolution set forth. For once Colby’s willing to do something for another no matter the consequences to herself. There may be hope for her after all.

Colby is screening at the Newport Beach Film Festival on Monday, April 25th.