Boy and the World is the animated Playtime that you never knew you wanted. Like Jacques Tati’s masterpiece, Boy and the World is a plea for the world to reclaim its humanism away from the clutches of technology. In the case of this film, that request goes to apocalyptic levels as technology swallows up everything from the music that reminds the main character of his home to the lush landscapes that serve as his playground.

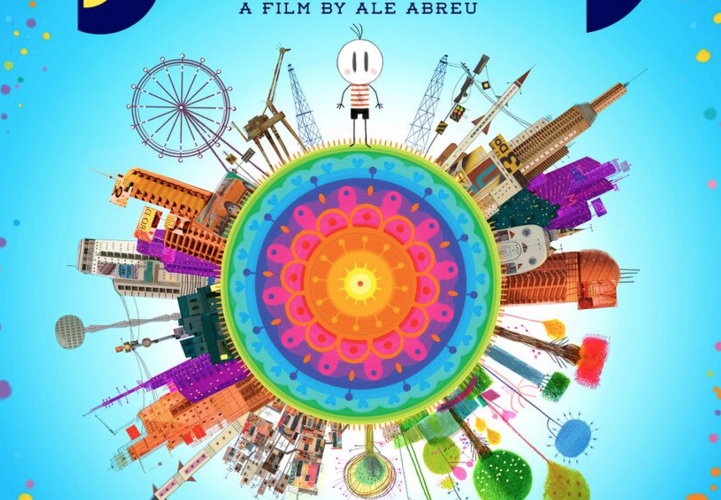

Alê Abreu‘s film has its own singular pulse from its first moment as kaleidoscopic imagery transports the viewer to a pastel odyssey of vegetation, animals and our own version of Monsieur Hulot, a tireless boy made up of five red lines, shorts, eyes, dimples and three hairs.

The plot is minimal. After his father — drawn in a manner resembling a Dia de los Muertos figure — leaves on a mysteriously humanoid train from home into the horizon for work, leaving behind the boy and his mother, the boy struggles with the change, missing the happy memories of listening to his father play flute and laughing together. One day without warning, he runs away in search of him with only his suitcase (filled cutely with one single family photograph).

Along the way, he meets world worn friends who are reenergized by someone who’s so unaffected by the modern world. The world away from the boy’s home is cold and alien, filled with garish monstrosities that resemble animals, but have none of the warmth or humanity.

Boy and the World is a kids film, albeit an incredibly dark one, but its psychedelic voyages into colorful, and later nightmarish fantasias, could just as easily make it a midnight crowd favorite. The visual style really can’t be underestimated, melding digital and analog styles to create a symphony of color and music.

All aspects of nature whether it’s the bursting jungles, weather, or adorably crude animals are drawn with a brilliant starburst of unreal pastel colors. Trees aren’t simply stalks, but blurs of scribbled purple acrobatically aligned with animals to the point where the viewer has no idea where one image ends and the other begins. All the while, every individual moment is underpinned by a parade of pan flutes, horns, strings and drums.

Technology on the other hand, is shown with encroaching collagist materials and smudged colors, violently condensing the color scheme into irradiated grays and browns. Cities are intentionally clumsily cut and pasted with varying individual elements that resemble a ransom note if it was conceived with pictures instead of words.

The industrial world is similarly packed with shadow parallels to nature. Two of the most striking images are the tanks which resemble elephants with their turrets drooping down like trunks, and cranes whose peaks are shaped like dragons’ mouths. But there’s plenty of stray details that lend a context of reality like an establishing shot that shows the main city as a landfill made up of skyscrapers.

It’s a remarkably engaging style of animation, and one that has effortless emotional resonance when accompanied by similarly analog and digital soundtracks. While elements of humanity are scored with earworm Tropicália melodies played with traditional instrumentation, the industrial elements are more abrasive, pitch-shifting and modulating instrumentation until they gurgle and hiss.

Every individual sequence has both its own melody and its own separate triggers for sounds. For instance, a scene waiting in traffic becomes a cacophony as cars make their own separate noises and traffic lights are mutated into a ghoulish honk.

The music doesn’t just serve as a harmony with the images though, it plays a crucial role in the plot as the individual notes mash up into an elemental force of humanity. But on a smaller scale, these notes beckon the boy forward on his journey.

It’s not merely the sheer amount of inventive imagery on screen, but how fluid and crisp the animation looks on the screen. Often set against a backdrop of white, the animation flows across the screen lithely, intersecting the boy with a variety of pastoral, and later industrial scenarios, ranging from cotton picking to a parade to basically a sweat shop.

The main characters are also distinguished by minute colorful details framed in rows of sameness. Attributes like a rainbow beanie and a tin can hat become their own memorable symbols within these tableaus. And the film is even generous enough to bring all of these characters full circle.

This isn’t just a visual feast, it’s a tremendously moving story on its own. Told through the POV of the child, the real life implications of the narrative are all the more frightening. As his innocence is gradually chipped away, it leads to an ending that’s as puddle-reducing as any of Don Hertzfeldt’s existential examinations.

Boy and the World does eventually lean too hard on its environmental message of technology ruining the Earth, especially in a scene that scraps away the animation for a montage of humanity’s destruction. But even with that scene, this is still one of the best animated films of the year, and a reminder that even the most familiar thematic ground can be revitalized with a unique approach.

Boy and the World is now in limited release.