The prestigious fifth feature from Darren Aronofsky, Black Swan, walks a fine line between being a balls-out B-movie and a fine Oscar picture. It can easily be argued as being either one, but ultimately it’s a feverish mix of both. It has compelling drama at its core, but it’s also got the stamping of an effective and hilarious horror film. Tonally, it’s all over the place.

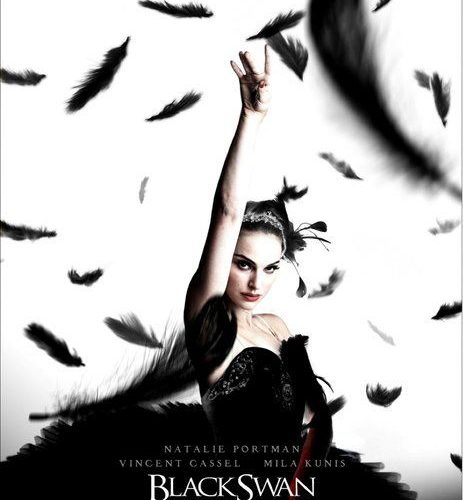

But Black Swan is undoubtedly one thing, a tremendous portrait of the artist as a young woman. Similar to nearly all of Aronofsky’s previous features, his latest is all about striving for greatness and the dangers involved. Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman) is a ballet dancer driving herself to madness in her quest for artistic perfection. She creates a delusional world for herself stemming from her prima ballerina role in the ballet “Swan Lake.” Everything is black and white to her, which is represented by the film’s color pallet and costume design. All the while her seductive surroundings fill her already clouded mind with sexuality and horror. All females are competition and all males are sexual predators.

Nina is surrounded only by destructive people. Her intimidating mother (Barbara Hershey), a failed dancer who takes her past out on Nina. Her director Thomas (Vincent Cassel), a brilliant, pushy and maddening artistic force to be reckoned with. And the only other prominent individual in her life is a rival, Lily (Mila Kunis, who once again shows the great acting chops she’s got in her, when given the chance).

Each character is ripping her apart slowly, but in the end Nina is the one behind her own undoing. She has the mindset of a child. She has no genuine love or compassion for anyone, nor is she receiving love from anyone. Once Thomas decides to do a rendition of Swan Lake and is in need of a star, Nina loses it. Swan turns into a psychological horror film along the lines of Repulsion and Suspiria.

And it’s also just as much of a body horror film. Anyone who’s seen a David Cronenberg film will see the obvious influence. Similar to Cronenberg, he embraces the B-movie shtick. There’s the usual mirror trick moment and some of the typical jump scares we’ve seen before, but Aronofsky smartly plays it all for laughs. Black Swan is a genuinely funny film, although many won’t look at it that way. On the other side, when Aronofsky wants to get under your skin, he dives to the core. The tension is squirm-inducing. There’s no standard bloody gags trying to pass themselves off as scares, but instead Aronofsky exploits the smaller things that can disturb nearly anyone; ripping skin off, broken toenails, etc. These are true moments of horror, which Aronofsky masters.

Black Swan is not completely original. It takes from a formula we’ve seen countless times before, but delivers a singular, masterful version that’s hard to forget. There’s a sense that maybe it doesn’t know this, considering a line that the director Thomas delivers about “surprising the audience.” Aronofsky never really does that. The story goes to the places and the depths you expect it to. But that’s not a slant, as Aronofsky makes this fairytale of self-destruction fly as high as possible.