After a string of hits in the 80s and 90s, director Rob Reiner has struggled to achieve the same success. Some of his projects post-2000 have made money and some have provided laughs, but none found staying power. It’s not all his fault. The best film during this period didn’t even garner a wide release and it was a real shame because Flipped held a worthwhile kinship to the likes of Stand By Me. So it comes as no shock to discover his latest worthwhile feature also harkens back to the coming-of-age drama with the trials and tribulations of youth. The difference is that this one isn’t about nostalgia. Being Charlie is instead about pain, family, and survival. It’s also about him.

Yes, it isn’t a coincidence that co-screenwriter Nick Reiner shares Rob’s last name — he is his son. Unlike growing up in the 50s and 60s with a famous father (Carl Reiner), however, Nick had to endure living in the spotlight and affluence of Hollywood when getting into rebellious trouble was as easy as walking down the street. He battled drug abuse, came and went through nine rehab facilities by his eighteenth birthday, and eventually found a creative outlet with which to begin his catharsis alongside fellow addict and co-writer Matt Elisofon. But rather than simply give us a one-sided glimpse of the suffering inside a troubled mind pitted against the world via emotional roller coaster, Nick had his father to remind him how he wasn’t alone.

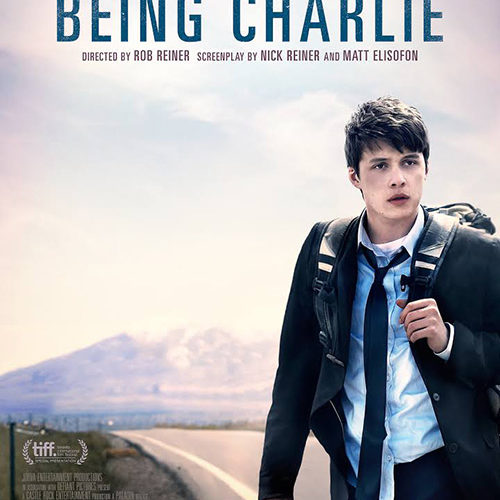

The film therefore straddles the line of rehab drama and familial strife. It becomes about the selfishness necessary to stay above water — the tough love, despair, and frustration that’s involved in getting to the other side when life refuses to allow you the time to simply find answers. Much like Nick’s father was constantly distracted from giving the attention he believes he deserved, Charlie Mills (Nick Robinson) must combat his dad’s (Cary Elwes‘ David) run for governor and the media scrutiny it supplies. On the surface it seems as though Charlie’s father doesn’t care about anything but the election and if it means shipping him off to in-patient care so be it. The boy appears angry and spiteful, rebelling solely to destroy David’s image. Surfaces are deceiving.

Being Charlie is billed as focusing mainly on this familial aspect, but I’m not sure it does. For most of the film David is shrouded in a dark light with Susan Misner‘s Liseanne playing the conflicted mother seemingly too weak to supply Charlie with what he needs and too blindly loyal in following her husband’s lead with little push back. I was actually surprised we were seeing so much of them during the first half because they were so stereotypically two-dimensional in this way. They forced Charlie into his latest program and served as sort of gatekeepers for freedom by standing in his way when the time came to earn a “day-pass” outside the rehab center’s wall. Thankfully they’re given more complexity in Act Two.

It may be too late to come across as totally genuine, but their love is welcome despite its lack of surprises as far as how it’s shared. I would have enjoyed more of their relationship and even more of a softening of David’s personal aspirations and lies (although I understand why Nick would write him this way due to his experiences with Rob who in turn talked him into the softening that does occur for cinematic sake). The parents are caught in a no man’s land of being present too long to forget and not long enough to drive actual impact beyond an inevitable chance at forgiveness. So despite Reiner saying this isn’t a film about addiction, it ultimately proves to be just that.

And that’s okay because the events Charlie goes through are what make the film captivating and resonate. To see him repay the kindness of strangers with theft and hear his cognizant yet agenda-filled opinion about why rehab leader Drake (Ricardo Chavira) does what he does is meaningful because it feels honest — hostile, but honest. Charlie’s trajectory is one of difficulty that should never be diminished because as halfway home counselor Travis (Common) says, “Scoring drugs is hard work, why should staying sober be easier?” He finds solace in love (Morgan Saylor‘s equally troubled recovering addict Eva), friendship (high school BFF Adam played by Devon Bostick), and empathy (Mom and a slew of residents who care during therapy). It’s rewardingly hopeful and conversely destructively volatile when things fall apart.

Credit the Reiners and Elisofon for refusing to sanitize this life and the tragic reality it brings to those caught in its wake. Some people die and some keep going despite it all. But the message we’re taught is that surviving isn’t luck or fate. It isn’t even the happy ending. Sometimes enduring the pain of watching those around you fall is worse than death’s emptiness. Sometimes loved ones must perish for you to open your eyes wide enough to keep going. The other shoe drops pretty rapidly towards the film’s end, but I can’t fault any decisions made. You can’t say some should have occurred earlier to space them out either since we do need a sense of victory to give the subsequent defeat power.

I enjoyed Misner and Saylor’s struggle to be strong and do the right thing despite how hard that is. Elwes as a former Hollywood star swashbuckler turned politician — the inside joke about fencing is cute considering he last collaborated with Reiner on The Princess Bride — effectively delivers the mask of anger and indifference hiding the emotional turmoil his decisions birth underneath. And Common provides a calming voice of understanding when Charlie desperately needs it. Where the movie truly excels, however, is the relationship between Robinson and Bostick’s characters. They are similar kids thrust down diverging paths that never forget the other no matter what. Every scene with them is authentic and funny until the laughter makes way for dark truth. That truth is Being Charlie‘s triumph.

Being Charlie opens in limited release Friday, May 6th.