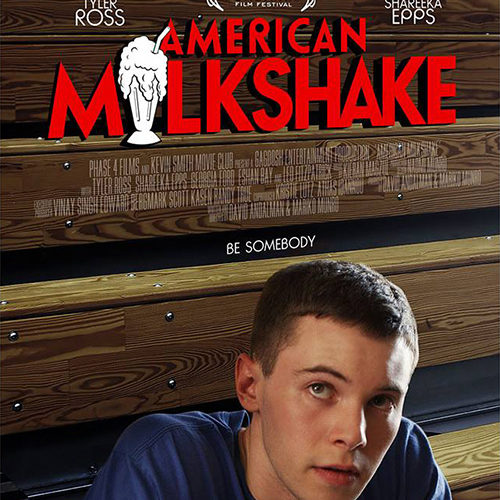

As someone who graduated with the Class of 2000, the idea of high school comedy American Milkshake taking place in the ’90s definitely piqued my interest. I often joke I’m a child of the ’80s despite knowing the descriptor doesn’t fit someone who was only eight at decade’s end, so seeing a film try to do to my teen years what The Breakfast Club did to the previous generation’s seemed exciting. After watching writers/directors David Andalman and Mariko Munro’s creation, however, I’m beginning to wonder if I was born too late because I seriously could barely relate to one thing that happened in this entire movie. Yeah, Street Fighter and Super Nintendo make appearances alongside bulky cell phones and pagers, but everything else besides the art production simply left me cold.

The weirdest thing about this reaction is that it almost appears to be exactly what Andalman and Munro wanted. Told from the perspective of Jolie Jolson (Tyler Ross)—the fictitious great, great grandson of The Jazz Singer’s Al Jolson—as he looks to infiltrate the projects-residing black kids on the varsity basketball team so he can gain their “edge”, everything is coated in a layer of adolescent naivety and insensitive ignorance. A senior magnate student secretly hooking up with the badass pregnant girl (it’s not his baby) he tutors in geometry named Henrietta (Shareeka Epps), Jolie is on the outside looking in with best bud Haroon (Eshan Bay). Unfortunately his uncomfortably calm maneuverings steeped in dumb luck to join the cool kids’ inner circle is nothing but a tedious journey with surprisingly minimal consequences.

This is the aspect that truly rubbed me the wrong way because had the film been told third person omniscient, Jolie’s actions might have held meaning. As it is now, the lack of discipline, punishment, and fallout only elicits a wry smile from our lead that ends up making him a highly unlikeable character. He eventually feeds his bud Haroon to the wolves when the nerd’s inclusion doesn’t fit self-interest, begins a relationship with a bulimic cheerleader named Christine (Georgia Ford) in the thought he can be with her at school and Henrietta in private, and honestly believes everything happening is some joke his cultivated “hard edge” allows him to ignore. He’s a racist, misogynistic, poser trying to aspire towards the glorifications of Tupac Shakur and an exonerated O.J. Simpson.

As a result, I’m at a loss as to what goal American Milkshake hopes to achieve. Does it show the universally misguided fantasies of youth without structure? Jolie’s father is a pushover while Henrietta’s is a hippie clueless to the fact she’s pregnant. Is it a portrait of culture hybridization being coveted for the wrong reasons? Jolie wants to be black because in his mind their race is gangsta. He doesn’t try to get to know his teammates as people; he wants them to be the caricature racially profiled on the streets every day. If the film has good points concerning identity courtesy of Haroon refusing to bow to social pressures and an epilogue-lite sequence uncovering everyone’s true selves beneath surface appearances, its path to such clarity is an arduous one.

I tried finding information on the internet to get a better idea of where the film was coming from but the only thing I dug up was a Facebook page devoted to its 90s aesthetic. With time warp photos of the cast and scrapbooked memories of events from the era ruling the page’s wall, it seems as though Kevin Smith’s Movie Club and partner Phase 4 Films are as concerned with exteriors as Jolie. There’s simply too much darkness underlining these characters’ actions to gloss over everything as “kids being kids” in a hip retro look. Maybe I don’t “get it” or want it to be more than what’s onscreen—I don’t know. I’d probably forgive the rest if it was laugh-out-loud funny, but the bone-dry humor forces me to dig deeper.

There’s another marker for why I should have been a child of the 80s—I’ve already become a crotchety old man who can’t find humor in a racist teen who honestly has no idea he’s racist while stereotyping everyone around him and loving them for exactly those abhorrent qualities. The performances possess an overwrought severity despite being within a comedy that kills all tonal consistency and ensures viewers will be more uncomfortable at what they’re seeing than entertained. Heavy issues like abortion, sexual abuse, gang fights, and more are glossed over and treated like children’s games everyone has played before and probably will again. So if Andalman and Munro’s mission was to expose youth culture’s immaturity and disgusting ability to make light of extreme tragedy, they might have done too good a job.

There is an inherent meanness to this display that even shakes Haroon’s likeable sidekick into embracing chaos. And while the performances are well-conceived with Bay, Ross, and Nuri Hazzard’s Arius finding authentic layers to depict, you can’t help wanting to smack them all for being carefree brats biting off way more than they can chew. Even Epps—who plays Henrietta as a sanctimonious educator failing miserably to open Jolie’s eyes to the truth of their world—partakes in the kind of childish behavior and misguided rebellion that makes her less and less sympathetic as the film progresses. Nobody learns a thing. It’s a heightened reality based in truth that ultimately seems to glorify the actions I want to believe it’s actually trying to vilify. I guess I’m just a bama, though, because I’m still lost.

American Milkshake hits limited theatrical release and VOD on Friday, September 6th.