Gaspard (Melvil Poupaud) arrives off a ferry and bustles up the road to the vacation house he will reside in for the next few weeks. He goes out for a quiet drink, avoids the bustling clubs, and returns to his apartment to tune a few notes on his guitar. It appears, for a while, that he won’t speak. What will bring this poor boy out of what seems like his purgatory? Luckily, Margot (Amanda Langlet), a pretty girl sporting a bright, red two-piece on the beach, invites him to chat. Once they start chatting, they will not stop.

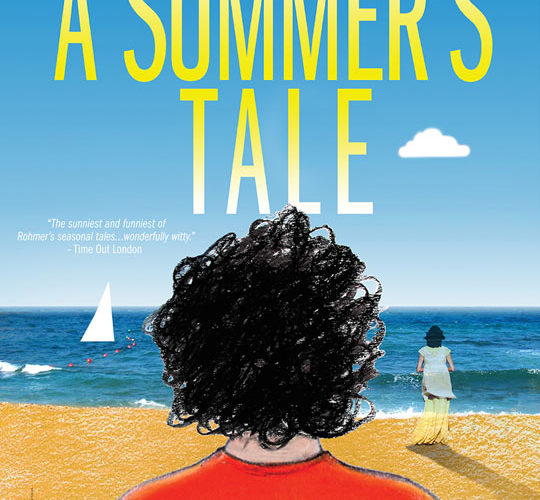

A Summer’s Tale might be the sex comedy Eric Rohmer never intended to have branded as such, but his 1996 film – finally getting a US theatrical release in a rather fine digital restoration (more on that later) – is a piercingly funny work of indecision. It can be odd to think the then-77-year-old Rohmer making a film as fluidly natural about the awkward romance of those in their ‘20s, but such a distance allows the director to lure us into Gaspard’s philosophies and principles before showing him to be less the victim than the instigator of deserved troubles. Gaspard’s “woe is me” logic toward love blatantly obscures the treasures before him, so when his romantic entanglements legitimately begin to escalate, the flaws in his own character hit deeper than a work which only positions these failings as external.

Rohmer’s conversational approach has defined most of his masterpieces (The Green Ray, My Night At Maud’s), but it’s not that his films are talky — it’s that they often seem to be veering off-course before almost bewitchingly coming upon a logical narrative action. When characters digress about their dispositions in real time, the moment the scene reaches its apex is a revalatory act, one that Rohmer asserts through a cut to a title card announcing the next day. It also develops plot on a natural path without evidently announcing the turns and twists of its melodrama — or, as Margot refers to them, “a habit of coincidences.” As it turns out, both Gaspard and Margot are in seemingly committed relationships: he to Lena (Aurelia Nolin), a seemingly fussy woman who may or may not show up in a week to join him; she to an unnamed archeologist halfway around the world. Although Rohmer plays with the will-they-or-won’t-they aspects of this relationship, he almost uses it as an excuse to have Gaspard reveal his own logic — a fear of love, his own justifications to remain at arms-length from others while simultaneously demanding that others give him all the affection he secretly desires. Margot goes for none of that, fortunately, and her playful gestures fill different roles for Gaspard: as a confessional companion for casual strolls; as a sexual foil, when one shot emphasizes her elongated leg in a Mrs. Robinson-like pose; as a trusted sidekick, when she wears a boyish hat; and as a paragon of romance, seen through a symbolic (and only symbolic) kiss.

Rohmer gets so much out of their long walks that it seems any desire for plot to commence might not be necessary. But Gaspard soon finds that this wallow for remaining unluckily in love is about to turn him on to a jackpot — a jackpot so large that he has no idea what to do with it. He first meets up with Solene (Gwenaëlle Simon), who gives him practically everything — except sex, at least not the first time; she has her principles, too — including a new obsession. Her own demands put a weight on him, however, Gaspard torn between what feels like a metaphysical love for the still-nonexistent Lise and what’s in front of him. (This is not even to mention Margot’s almost untenable contempt for his ghastly, unemotional logic in pondering how to convenience this inconvenient situation.) Things become even more complication (and cringe-inducingly comical) when the metaphysical becomes physical as Lise arrives. The airy seas and bright sun which seemed like an escape soon to turn into a prison, the skies becoming more cloudy and the rocks turning, it seems, into almost-alien colors.

What’s a guy to do! The comedy of it all probably wouldn’t work if Rohmer didn’t allow Gaspard to essentially hang his own gallows. While seemingly sympathetic, the further he dives into his high-wire plate-balancing act, the more obvious it becomes that Gaspard has no more interest in any of these women than whatever might be easy for him. He confesses to Margot that Solene must be the ideal woman, only to reveal one day on that it’s truly Lise, only to then decree his (platonic, but only out of suitability) relationship with Margot as what he truly desires. Rohmer’s camera plays with these rhythms, especially through the physical presences of his three actresses: Margot’s playful, bouncy energy; Solene’s direct and consuming kisses; and the zig-zag energy which brings Lise in and out of his frame. It might be easy to see why Gaspard can’t decide, but it’s also pathetic when his boyish looks always carry a weight of indecision as he moves around like a chicken missing its head.

In the end, this delightful comedy is filled with a melancholy that releases tension through a sigh instead of a breath of fresh air. A convenient phone call saves him from an impossible decision, something Gaspard feels all too happy to revel in while Margot slowly unveils her true emotions through a physical gesture. Dan Sallitt notes that the “light-comic tone and an idyllic vacation ambience culminate in emptiness and desolation,” and it’s hard not to feel the pain accompanying these comic (and cosmic) gestures.

It’s all been beautifully preserved as well in this digital restoration; the colors pop off the screen while feeling perfectly authentic, and the motion moves without much trace of awkward static. Only the grain can look somewhat awkward against the tanned bodies and, especially, during night-set scenes — a necessary evil, given the constraints of non-celluloid restoration. To have what is certainly one of the finest comedies of the year — or any year — presented in very fine form is a delight, and a reminder that idle talk can be as thrillingly alive as visceral action.

A Summer’s Tale is currently in limited theatrical release.