From ghoulies and ghosties

And long-leggedy beasties

And things that go bump in the night,

Good Lord, deliver us!

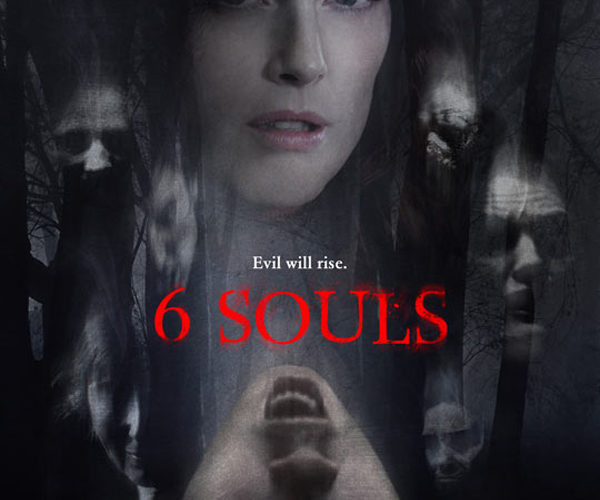

It isn’t known which of the ancient Scots first conceived that evocation above, but I’m calling for an amendment that would add ‘bad religious thrillers’ to their list of arcane forces. This category would most assuredly include Julianne Moore’s ludicrous new horror 6 Souls, a movie so daft that it drops the phrase ‘Satanic mountain witches’ without so much as a blink or pause. Moore, once the bright symbol of the indie film scene, delivers a surprisingly delicate performance in what amounts to the silliest movie I’ve seen this year. There’s absolutely nothing in Souls you haven’t seen somewhere else, done with less embarrassment.

Swedish directors Måns Mårlind and Björn Stein (Underworld: Awakening) open the film with a sweeping camera shot that cranes past rain-soaked windows, looming clocks, grim-eyed officials and settles on Moore’s psychiatrist in the center, sharing a vile story of a psychotic man who raped a young girl and then tried to remove her ovaries. This piece of dime-store dread serves as a microcosm of the film at large, demonstrating everything both wrong and right with 6 Souls, and how often those two facets collide with one another.

While skillfully composed, the direction is hectic and leans heavily on pulpy imagery it never actually earns or understands. The writing feels like it was vomited straight from a Dean Koontz novel and every actor seems to adopt a different tone. The technical credits are strong and some of the familiar atmosphere works, but it’s too generic, too frantic, and when the film allows Moore’s Cara to share her belief that ‘multiple personality disorders were just a fad’ it plays even more hysterical than it might otherwise.

At first, it appears that 6 Souls might pull itself out of the neo-gothic muck and deliver a psychological thriller worthy of its star. The early passages are interesting as overheated pot-boiler fiction, and tease a better, smarter movie. Most compelling is the relationship between damaged but devout Cara, and her agnostic, intellectual father, who tries to push her back to the land of reason and logic with a prickly new case. This new patient, Adam, is afflicted by multiple personas that turn out to be the identities of actual people, now dead. Kind of creepy, isn’t it?

As people around Cara begin to die in strange, confounding ways and her daughter starts developing the symptoms of the victims, the God-fearing doc heads up into the mountains where she encounters Granny, a faith-healer witch that makes the hag from Pumpkinhead seem like a documentary character. In scenes that look like they were left on the cutting room floor of Winter’s Bone, Cara learns from Granny about ‘the sheltering’—an act that removes souls from individuals and places them in others. In an eye-rolling revelation, only the faithless seem to be targets of, well, whatever exactly is happening.

Jeffrey De Munn is a greatly underrated character actor and his turn as Cara’s dad meshes well with Moore’s own approach to the material, which is to fixate not on the spooky events but how they affect or infect individual world-views. Moore never falters in making Cara a realistic and multi-faceted entity, even if Michael Cooney’s screenplay can’t decide if she’s better off as the rigid skeptic or as the terrified woman of faith who is ready to take on Adam and his spook-show with the fire of unwavering belief.

Jonathan Rhys Meyers, as the plighted Adam, has the worst role of the whole enterprise, attempting to change mannerisms for personalities that only exist to generate jump scares. His character is lost amidst too many conflicting back stories; he might be a paraplegic named David, or a centuries-old cursed preacher who communes with shadows. Meyers wants to give him a sense of unmoored psychic scarring, but the film has positioned him as a sinister heavy, and the understated approach turns the concept to mush. When he shows up at Cara’s daughter’s soccer game and behaves like a friend of the family, it’s supposed to be suggestively creepy and instead feels false and silly.

Somewhere deep inside this tangled knot of clichés, jump scares and supremely stupid twists there exists a semblance of an interesting idea. Instead of coalescing in a careful examination of what faith is and how it can damn or redeem us, the conceit is simply treated as one more carry-over from the pillaged genre factory. Stephen King used to complain that God had become an incidental convenience in horror stories, with priests showing up to wave a cross and holy water, vanquish evil, and then recede. The characters in 6 Souls don’t have even enough gumption to do that, and mostly whimper and whine while the darkness closes in.

6 Souls is currently in limited release and available on VOD.