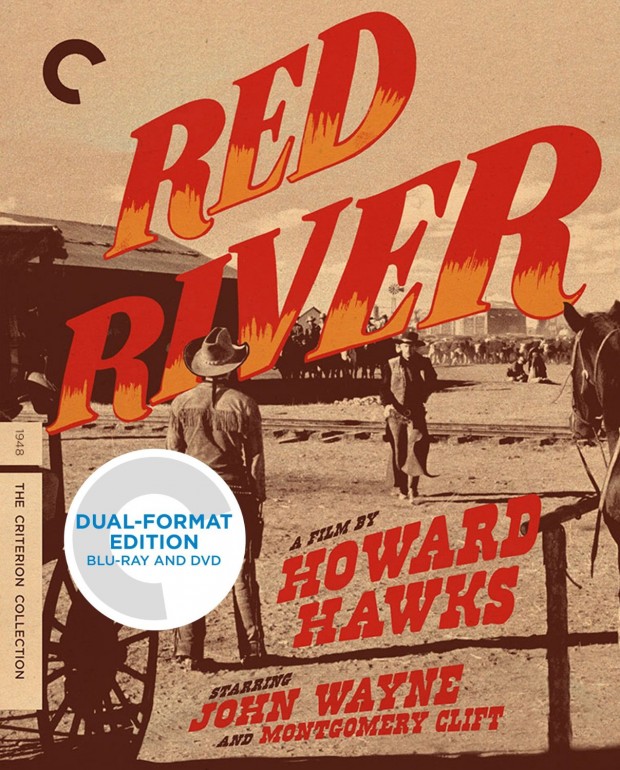

Red River is truly one of Howard Hawks’s greatest works, and possibly one of the more surprising films in his career. After all, it’s one of his few films of his to spin an epic tale – the creation of the Chisholm Trail – while seamlessly remaining a psychological portrait of men. Compared to the relaxed moods of Rio Bravo or Only Angels Have Wings, the anxiety that pervades Red River is apparent from the early shot of Thomas Dunson (John Wayne) and Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan) staring back at the smoke from the caravan they just left, climaxing in an exasperating moment with one of the strangest and, somehow, more transcendent endings of any Hollywood film. Along with its reputation, however, there is controversy over what, exactly, is contained within. Its release on Criterion is perhaps more of a cause célèbre than most others — this package not only includes the version that has been readily available for years, but also “the rarely presented original theatrical release version, the preferred cut of director Howard Hawks.”

A director’s cut? Wonderful! But, looking further into Red River, the story gets a bit complicated — very complicated, actually, which I originally parsed out in an essay for Masters of Cinema’s release of the film last year. Criterion — as well Peter Bogdanovich, in his interview on the discs — have smartly avoided using the phrase “director’s cut,” which would be a misnomer. It wouldn’t be the first time that phrase was incorrectly used for this film, either. Picking through the details of how each cut came into existence (and which cut viewers should really watch) is not as simple as other films with conflicting versions, which often come down to a studio cut and a director’s cut.

Criterion has labeled these two versions the Theatrical Version and the Pre-Release Version. The Pre-Release Version was Hawks’s first cut of the film, running 133 minutes; the version that finally went out to theaters in 1948 was cut down to 127 minutes. Watching these two cuts, the most notable difference is the use of a voiceover by Groot in the Theatrical Version, while the Pre-Release Version employs a series of dissolves with pages from a book entitled Early Tales of Texas. (In cinephile circles, the two cuts are thus known as the Voice Version and the Book Version.) It is this latter cut that has been widely available since the early 1990s, while the Theatrical Version has only been available on a UK VHS (or collector 16mm prints).

There are conflicting reports following how and why the Book Version became the definitive copy. The term was first used in conjunction with the film in a 1990 Los Angeles Times story by Scott Eyman. Eyman writes, “For more than 40 years, the version of Red River that was available in theaters and on television was seven minutes shorter and differed in essential story points from Hawks’s original intentions.” He later goes on to quote MGM Classics president Michael Schlesinger: “The negatives were sitting forgotten in a corner of a vault, waiting to be used,” who labeled the VHS and LaserDisc release at the time as the “Restored Director’s Cut.”

However, it seems unlikely that the Book Version had simply been sitting in a vault. How else could Bogdanovich ask Hawks about it in an interview in Who The Devil Made It, where the director declares that his definitive cut included the voiceover. He tells Bogdanovich, “All the TV prints seem to have been made from that version and you can’t even read it on TV because it’s too small.” This correlates with Gerlad Mast’s assertion in Howard Hawks, Storyteller — which includes the most thorough examination of the two versions — that United Artists struck new prints from the Book Version negative for a re-release, and possibly never had the Voice Version negative because it was rushed to theaters.

Was the use of the Book Version as a director’s cut simply a case of marketing? For whatever reason, the Voice Version of Red River was buried, despite Bogdanovich emphasizing Hawks’s original intentions for years. This is, of course, all very strange, given the history behind its editing. Hawks had been absent for much of it (having left to direct I Was A Male War Bride), leaving editor Christian Nyby to do a lot of the heavy work, (He was allowed to direct The Thing From Another World as a thank-you.) It was during this time that the most notorious change was made by another Howard – Hughes, of RKO, who argued that Hawks had “stolen” the ending from The Outlaw, which the director had worked on without credit. According to an August 20, 1948 Los Angeles Times article, “[Hawks] used a climatic scene from Hughes’ screenplay,” which is likely true – a 1970 Film Comment interview with Borden Chase outlines his own ending for the script, which stays true to a Saturday Evening Post serial he wrote. Thus, the Voice Version of Red River eliminates a few shots and a few lines by Dunson declaring that Matt draw his gun near the end. The ending in the Voice Version thus feels choppy and unbalanced — Matt’s stone-cold conviction is essentially missing, which is to say nothing of Wayne jumping literally 10 feet via a continuity error.

Why would Hawks support this version if the ending feels off? His complaints about the television and being able to read feel a bit unjustified, and, as a director whose films are often defined by their “hangout feeling,” to make a film shorter seems odd. The deleted scenes, themselves somewhat hard to parse, are mostly those related to Matt, building his own anxiety regarding Dunson, which filmmaker and critic Dan Sallitt argues “really help the film feel more like Hawks and less like [screenwriter] Borden Chase.” (One odd note, however, is a purported longer description of Cherry Valance’s “girl from Abilene,” which both Mast and Todd McCarthy discuss. I could not locate this sequence while comparing the two.) The voiceover is, too, uncharacteristic of Hawks, though it does show up in Hawks’s sister film, The Big Sky, charting part of the creation of The Oregon Trail. But Groot’s narration, while close to the text, also directly lays out many of the psychological feelings of the characters that feel overdone, especially when Hawks grounds so much of the work in his visuals.

Why would Hawks support this version if the ending feels off? His complaints about the television and being able to read feel a bit unjustified, and, as a director whose films are often defined by their “hangout feeling,” to make a film shorter seems odd. The deleted scenes, themselves somewhat hard to parse, are mostly those related to Matt, building his own anxiety regarding Dunson, which filmmaker and critic Dan Sallitt argues “really help the film feel more like Hawks and less like [screenwriter] Borden Chase.” (One odd note, however, is a purported longer description of Cherry Valance’s “girl from Abilene,” which both Mast and Todd McCarthy discuss. I could not locate this sequence while comparing the two.) The voiceover is, too, uncharacteristic of Hawks, though it does show up in Hawks’s sister film, The Big Sky, charting part of the creation of The Oregon Trail. But Groot’s narration, while close to the text, also directly lays out many of the psychological feelings of the characters that feel overdone, especially when Hawks grounds so much of the work in his visuals.

Bogdanovich stresses that perhaps the perfect way to watch Red River is screening the Voice Version until Wayne starts crossing those cattle, then quickly pop in the Book Version to get that final showdown done right. While perhaps a little less intimate, part of my own preference for the Book Version is the way it contrasts the myths and reality Hawks paints. The text gives only the basic details of what happened on the tour, while Hawks’s scenes give a sense of the real duels between the men, painting a complicated portrait between Matt and Dunson that eludes simple matters of right or wrong.

While Hawks preferred the Voice Version, we may not wish to take his word as the final say. In a conversation with Sallitt, he told me about a Hawks conference, attended by the director in 1977, where they were showing a number of his films, including The Big Sleep. As the picture ran, Sallitt and the other Hawksophiles immediately noticed that the print they were seeing was not the 1946 cut, but what was later understood as the 1945 version that had been shown overseas to troops (so obvious that even one of the actors playing Eddie Mars’s wife was differently cast). When Sallitt and others later inquired to Hawks about this version they had never seen or even heard of, the director responded that it was the same film he’d always known.

Perhaps an honest mistake by Hawks (he was only months away from death at the time), but when there are so many versions of his films (e.g. Scarface and The Big Sky), it is perhaps a case of taste. After all, Criterion provides both versions of the film for your own choice, and who knows what issues we’d have run into if they tried to splice the two together. The mystery of which version of Red River is closest to Hawks’s intentions may never be solved. But what remains on the screen — Wayne’s hardened face, the hordes of cattle that seem to stretch on endlessly, Joanne Dru’s flirtatious reaction to being shot with an arrow, and Clift’s steadfast eyes — will stay iconic.

Red River is now available from Criterion. Watch a BBC documentary on John Wayne‘s life and career above, which also discusses the film.