New cinema-centric books have dropped from some major names, including Anne Thompson and David Thomson, and tackle some of the great films of the last four decades — Network, The White Ribbon, err, Showgirls …

As usual, it’s a gloriously mixed bag — Showgirls! — but all are worthy entries in the canon of film criticism. In fact, Adam Nayman’s spirited defense of Paul Verhoeven’s much-abused stripper-epic is one of the most enjoyable books of its type in some time. Scratch that — of any type. Check out our rundown of recent, recommended books below.

The $11 Billion Year: From Sundance to the Oscars, an Inside Look at the Changing Hollywood System by Anne Thompson (Newmarket for It Books)

In The $11 Billion Year, Thompson on Hollywood editor-in-chief Anne Thompson attempts to present “a slice of what happened during a watershed year [2012] for the Hollywood movie industry.” It is not, Thompson writes, “the whole story, but it’s a mosaic of what went on, and why, and of where things are heading.”

Any year with offerings as diverse as Les Misérables, Django Unchained, The Avengers, Silver Linings Playbook, and Life of Pi is worth this level of analysis, and while it is difficult at book’s end to determine exactly what 2012 added up to, this is not for lack of trying on Thompson’s part. In this nod to William Goldman’s influential Broadway study Season, Thompson includes almost every moment of zeitgeist-impacting relevance, from Beasts of the Southern Wild’s Sundance debut to Argo’s success at Telluride and Zero Dark Thirty’s still-controversial response.

And befitting her insider status, Thompson even includes details such as this Oscar party tidbit about Ben Affleck: “Affleck goes into the men’s room and shaves off the beard he wore, superstitiously, throughout the season. He doesn’t need it anymore.”

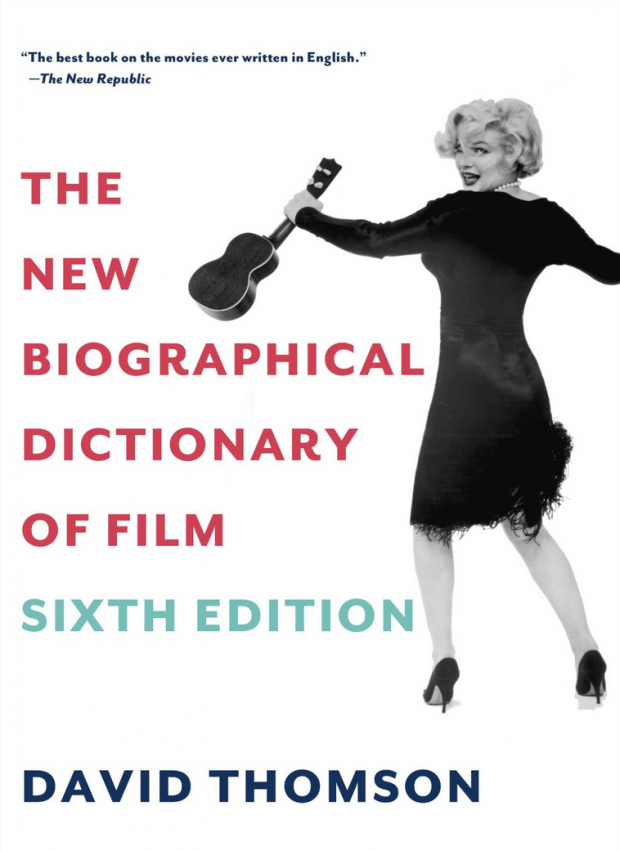

The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Sixth Edition by David Thomson (Knopf)

Before one starts paging through the latest edition of David Thomson’s The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, it is intriguing to eyeball the years in which previous editions were released: “Copyright © 1975, 1980, 1994, 2002, 2004, 2010, 2014.” Think about that for a moment. The author has been compiling, revising, and rethinking this text for nearly 40 years now. In his introduction, Thomson elucidates on how the book began, and how it has changed over four decades:

“I was offering an interpretation of film history, and it has been a great upheaval in renewing the book because so much has changed since 1975. This book was written first without a computer, databases, or the resources of video. It grew out of lists made in the library of the British Film Institute. … If I were starting this book now (and that would be as far-fetched a publishing venture as it was in 1975), I think it would have to include the inventors and creators of the Internet. But I don’t know enough to pursue them; and perhaps I am running out of the energy. I hope not.”

If this latest edition is any indication, no, Thomson is not running out of energy. In fact, he has smartly broadened the scope to include more television: “This sixth edition admires people like Bryan Cranston and Elisabeth Moss (from Top of the Lake), in the spirit that reckons many of the best movies are made for what we still call ‘the small screen.’” It is interesting to ponder what mediums may find their way into editions seven and eight.

Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies by Dave Itzkoff (Henry Holt and Company)

If ever a ’70s classic deserved its own creation/impact story, it is Sidney Lumet’s Network, and New York Times culture reporter Dave Itzkoff is the ideal man for the job. Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies is wildly entertaining, and may go down as the only book in literary history to feature interviews with Warren Beatty, Shirley MacLaine, the aforementioned Affleck, Keith Olbermann, and Bill O’Reilly.

It is a fast-moving read, to be sure, but I found the pages devoted to the film’s aftermath to be its most riveting. There’s a “stand-off between [William] Friedkin and the Network” team at the Oscars, crushing reviews from Frank Rich and Pauline Kael, the sudden death of Peter Finch one month before he won an Academy Award for Best Actor, and, of course, Faye Dunaway’s infamous “Is that all there is?” pool-side photograph the morning after her Oscar win.

A Companion to Michael Haneke, edited by Roy Grundmann (Wiley Blackwell)

It was only a matter of time before publisher Wiley Blackwell’s “Companions to Film Directors” series made room for the downbeat Austrian master Michael Haneke, and indeed, a hardcover book devoted to his work was released in 2010. That mighty tome has finally been released in paperback form, with a new preface from editor Roy Grundmann that briefly tackles Haneke’s latest triumph, Amour. If there is any flaw with the dense (it comes in at slightly more than 600 pages) essay collection, it is the non-inclusion of Amour outside of that preface.

But what is here is profoundly involving, even though there is also little text devoted to The White Ribbon. Charles Warren’s “The Unknown Piano Teacher” is especially fascinating, as is the Caché-centric “Multicultural Encounceters in Haneke’s French-Language Cinema,” by Alex Lykidis. The final section in the book, titled “Michael Haneke Speaks” even includes a wonderful piece by Haneke himself, a translated look at Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar.

It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls by Adam Nayman (ECW Press)

If there is one sentence that demonstrates exactly why Adam Nayman’s It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls is such an astute, enjoyable read, it is the following: “This scene poses a particularly challenging Masterpiece/Piece of Shit conundrum.” Masterpiece, or piece of shit? Is it possible Showgirls is both? Nayman thinks so:

“Either Showgirls is a piece of shit — the received wisdom, and for a long time the majority view — or it’s some sort of trashy masterpiece, which is the revisionist claim. Behind Door #3, however, lies the tantalizing possibility that the movie might be both at the same time, a masterpiece that is somehow a piece of shit.”

Nayman analyzes that assertion with wit and insight, breaking down the film’s most maligned scenes (Nomi’s “dry-hump choreography” in the swimming pool, for one), discussing the responses to Elizabeth Berkley’s go-for-broke (to put it mildly) performance, and contemplating the film’s role in the Verhoeven oeuvre. (Verhoeuvre?) The book is, quite simply, stiletto-sharp, and succeeds in something extraordinary: It makes one want to revisit Showgirls not for laughs, or titillation, but for (gulp) understanding. That’s some accomplishment.

Which of the above books will you pick up?