On a basic level, Paul Thomas Anderson makes films about magnetic presences — figures who emanate such greatness that it’s nearly as impossible for bystanders to be around them as it is to not be around them. Phantom Thread, Anderson’s ninth film, is of a piece with much of his career in that way, telling of a prodigal 1950s dressmaker, Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis), who inspires equally rapturous reactions to his handiwork and his mercurial disposition.

Just as The Master unmasked a serious-man character study as a psychological survey of bullshit artists and Inherent Vice played dress-up as a noir story to spin a tale of immovable sadness, so too does Phantom Thread present itself as a rigorous biopic-like narrative while its interests are far less fussy or predicable. This is less an examination of a singular person than a look at the torturous and sublime experience of his creative process as it relates to the most important people in his life.

In some ways, that description situates it as a bedfellow to this year’s earlier excoriation, mother!, but to say so also sells its ambitions short. This is an unexpectedly inclusive and more well-rounded portrait, one that’s unflinching in lingering on the wounds artists inflict in their wake — and one that’s also far from a martyrdom of that emotional destruction, thanks in part to a formal modesty, levelheaded tone, and two incredible female performances.

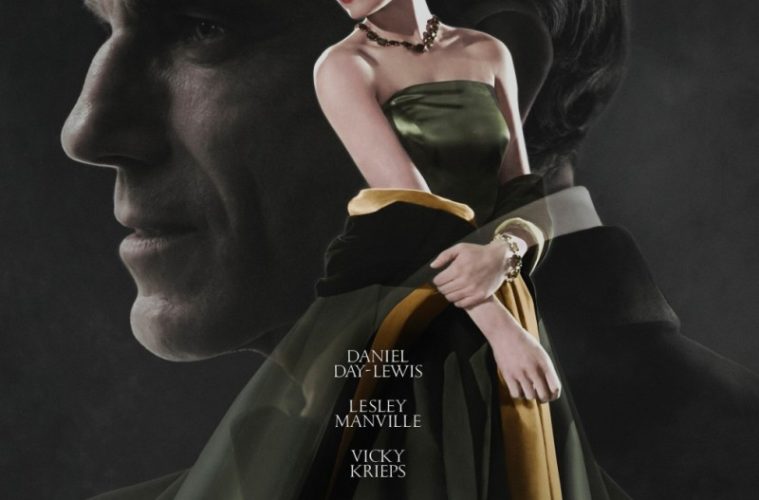

At its center, Phantom Thread revolves around the relationship between three people, with Woodcock as its axis. Cyril (Lesley Manville) is Woodcock’s sister, confidant, and companion, a woman who has fought tooth and nail for her place at Woodcock’s side and now rules with wizened imperiousness, while Alma (Vicky Krieps) is a late arrival, a new muse for Woodcock who has no interest in being an inspiration as temporary as the season’s fashion. In focusing on these three characters, it becomes less about the friction between them than an uncomfortably astute portrait of the cycles of need in relationships. Sometimes that’s in flashes of desire; at other times it’s in challenging the assumptions of how people need to act in front of others.

The performances work in concert with a similar intimacy. Long and understandably the poster child for method acting, Day-Lewis delivers a performance that isn’t an obvious last grasp for a gold statue. He’s an expectedly domineering presence, prone to cantankerous outbursts and enunciating his words with a gentle thoughtfulness, but his essential characteristics are in service of the film’s simultaneous enchantment with and clinical admiration for fashion. True to the eye of a designer, Day-Lewis is spellbound by movement and flow, but even his most tender behavior has an air of possessiveness, rarely more clear than during a great scene where an initially sensual modeling with Alma leads into an all-business marathon of measurements.

A relative unknown on these shores, Krieps is nothing short of stunning as Alma, deftly communicating a lifetime of experience with Woodcock and a complex discomfort with the camera’s gaze without becoming decentered in the process. Compared to some recent Anderson heroines, Krieps’ character isn’t shrouded in mystery or a dark unknowability. This is just as fully her story as the genius dressmaker who is physically incapable of not commanding the spotlight, even as he detests the attention. An encapsulation of her consuming love, burgeoning ego, and the ways that affection magnifies the self, Krieps’ performance defies the common portrayal of the classical muse.

Cyril’s character likewise subverts expectations of a professional partner. She’s expectedly a barrier, but through Manville’s layered performance and an evident worship of routine, there’s a social anxiety and unseen experience that’s communicated effortlessly, even as her character flits in and out of the film – often literally.

That lingering sense of tradition and isolation threads through the film in rich and unexpected ways. London is less a setting than a vague understanding of the outside world. Rather, the action is nearly entirely contained within the House of Woodcock, a baroque mansion that’s speckled with the same sense of legacy and refined civility that goes into their output. True to the era and Woodcock’s own real-life inspiration (reportedly British fashion designer Charles James), the dresses are exceedingly generous, gorgeous centerpieces that still ably echo Alma and Woodcock’s own worries about their respective obsolescence.

The passage and feel of time has long been a preoccupation of Anderson, but the rhythms here are decidedly unique. Reuniting with There Will Be Blood editor Dylan Tichenor and composer Jonny Greenwood (who, with a mix of classical music, has made perhaps the best score of his career), they’ve created a film that feels engulfing and less jagged than recent Anderson outings — more attuned to individual performances and the power of body language. At times, it feels more in line with Terrence Davies or Jane Campion than anything in Anderson’s prior oeuvre.

In an uncredited collaboration with his camera team, Anderson delivers far more restrained visual work than one might except given the occasional pageantry on display. Luminous but tempered with a beguiling harshness, the pyrotechnics are less in individual shot compositions than the ways they contribute to the larger rhythms and the emotional place of these characters. One of the most memorable shots comes late in the film as Alma is forced to fade into the background. She watches Woodcock working as the camera slowly pans, only enough to keep her at the fringe of the frame. It’s these recurring moments that consistently remind the viewer that there’s room for more than one person in this story.

It’s tempting to view Phantom Thread in the context of Anderson’s own self-mythology, but it’s also never felt more wrong. Shapeshifting films aren’t new for him, but this feels like the beginning of a different version of the filmmaker: one who’s more mature, more confident, more open, and a director who will continue to keep surprising all of us.

Phantom Thread opens on December 25 in limited release and expands in January.