In the dictionary of Received Critical Wisdom, we are told that the way to turn a play into something cinematic is to open up the space. Plays can only take place in one setting, so the obvious cinematic solution is to have invent settings. Just recently, I heard A Voice of Critical Wisdom explain the genius of Mike Nichols’ debut feature, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was his ability to move the play’s action outside of the house.

This approach to understanding cinema is, without a doubt, a highly limited and ignorant one—first for suggesting that some approaches are “more cinematic” than others. (A security video of a parking lot is just as “cinematic” as Citizen Kane.) But even more egregious is the assumption that the difference between theater and cinema is simply a matter of multiple spaces. The central and greatest difference between theater and cinema is the camera. From there, directors can use the camera to express, manipulate, and direct in a way that changes the stakes of theater. And in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, now debuting in a magisterial Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection, the canonical German director does exactly that.

Petra von Kant came in a wave of the director’s plethora of features made in the early 1970s (one of four released in 1972 alone), and remains one of his most celebrated efforts. Most notably, it was the first in which the German director began exploring and reconstructing the American melodrama — Douglas Sirk being the obvious nod, though one character directly cites Joseph Mankiewicz — which became a key aspect of films such as Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and Martha.

For those who know their cinematic history, the “one-room” movie set is nothing out of the ordinary. From Hitchcock’s Rope and Rear Window to Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men to even the recent Locke with Tom Hardy, directors are just as fascinated by exploring a single space as linking multiple spaces. The question, then, is how one uses the camera to make the space more than just a theater. Fassbinder may have started as a neo-Godardian, but the cinematic material of Petra von Kant is more lucid and more streamlined — less engaged in breaking the artifice of its own materials than deconstructing the drama at hand.

The camera has a more searching quality, moving through the space as we watch our titular heroine (Margit Carstensen) prepare for another day of lounging around in her bed. Her mute (by choice or by biology?) servant, Marlene (Irm Hermann, in one of the truly great screen performances), helps her around the house, finishing the drawings for the fashion designs she is working on. But, more than anything, Petra sees herself as a feminist hero, having defiantly divorced herself out of an unhappy marriage in favor of independence. But to err is to be human. Petra’s Neiztchian superweiblich has her own interests, and when by chance she meets the lusciously virginal Karin (Hanna Schygulla, Fassbinder’s wife), her theoretical desires are replaced by tangible ones, at which point the melodrama hits full throttle.

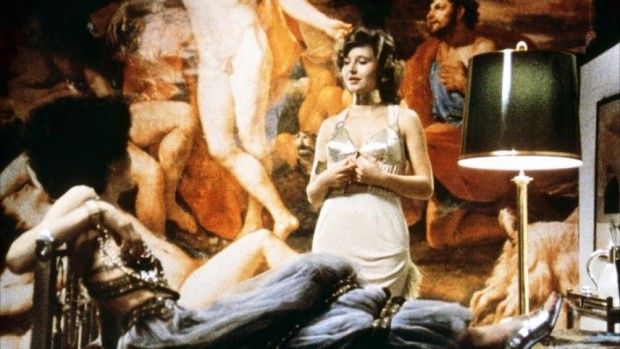

The influence of Sirk is apparent from Petra von Kant‘s first frame, as the film’s luscious color scheme, designed by DP Michael Ballhaus, pours through every inch of the frame, the blindingly bright room often contrasted with the dark shadows of where Marlene must work. And the film’s mise-en-scène (Kurt Raab as production designer, Maja Lemcke as costume designer) similarly pops out toward us — the overflowing white rug; Petra’s boisterous blonde wig; the gargantuan, Renaissance-like mural of female pleasure plastered on one wall; and Marlene’s slick, long black dress. Hermann’s role is key — a desired longing in a position of sadomasochism. An early dance to the tune of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” signals the chance for something more open and expressive between them, a moment of beautiful stasis and pure love that is still only something temporary. But otherwise Marlene often remains in the background, her gestures of emotions limited to the way her hand suddenly shakes or the pause she takes when overhearing an unremarked dismissal by her dominant lover.

Hermann’s emotions are always registered by the camera, which is constantly searching through this environment to place the various actors into new relationships. There is a certain static element to Fassbinder’s direction; he seems to have conceived the film in a series of tableaux shots (hello, #PerfectShots!). But these are only the building blocks for Fassbinder’s drama, because it is the sudden movement of characters, such as Petra’s swift lunging for a phone, that registers as the most exciting moments in the film. This is why Fassbinder’s approach to acting style, a neo-Brechtian reduction to the monotonous, actually becomes frighteningly real. Petra can easily recite her thesis of her unemotional detached lifestyle, but when chance enters the picture — first in terms of desire, later in terms of mourning — these little pockets of emotion called humanity slip through like lightning in a bottle. And simply watch for a small, not-entirely-casual drop of a gun into a suitcase in the film’s excitingly brutal final shot. A minimalist approach to acting does not concede it to be without expression.

Much more classical, however, is the film’s rhythmic editing. Perhaps showing more Mankiewicz influence, Fassbinder often cuts on the various beats of the drama — the kind where, if directing in the theater, you would mark on the script for an actor to make a grand gesture. But Fassbinder can use the camera create the shock, often cutting to a reacting face to register the sudden shift in emotion. Along with the camera’s tendency for rack focus and zooms, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant moves with extreme velocity as it travels through the ups and downs of its melodrama. And for something that’s often about the limitations of the female role in society, this helps the film feel as fluidly possible to opening up into an infinite amount of directions while remaining deliberately closed. And what better to define cinema — Scorsese’s declaration of what’s inside and outside the frame — than the understanding that a film being limited to one space hardly means it’s anything but the purest of its medium?

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant is now available on Criterion.