Based on a 2012 novel written by Kanae Minato, The Snow White Murder Case is very much a product of our time. A satirical take on the Twitter age that also to a point provides a compelling murder mystery reminiscent of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, the story’s as much a social critique as it is dramatic fiction. Our world is currently ruled by attention deficit to the point where journalistic integrity has been usurped by the necessity for click bait popularity. It isn’t enough to simply state facts when there’s so much competition out there for media dispersal. Now we must hire charismatic shock jocks to salaciously speculate in ways that care little for the unsuspecting victims left in their wake as long as viewers tune in.

News is entertainment. We all watched OJ Simpson hiding in that white Bronco and trying on those infamous gloves. For whatever reason we cared about Robert Blake and Phil Spector’s fate simply because we recognized their names above the myriad murder trials happening all over the country that aren’t being shoved down our throats ad nauseum. Just like reality TV, America watches for the train wreck stimulation rather than any educational desire to keep up on current events. We revel in the pain of others by both willfully exploiting those who were wronged and cheering for the lawful vengeance we hope rains down upon the guilty. Rather than let the professionals do their jobs, we wax on and on about things we know little about as sport. In the 21st century you’re guilty until proven innocent.

The best thing about The Snow White Murder Case is that it shows we in the US are not alone in this truth. Even Japan is ruled by ratings and the covetous position of being first to break news. Murders no longer need to be announced via the nightly news when the masses on Twitter can tweet all their followers about the police officers swarming towards the scene. Rubberneckers now have a voice to beat the media—some doing so to help others avoid the traffic such an event causes while others hope to be approached for their fifteen minutes to explain everything they didn’t see happen. And if the victim is an unknown cosmetic company office worker like Noriko Miki (Nanao), few may care at all until the case finds itself in a position to serve their benefit.

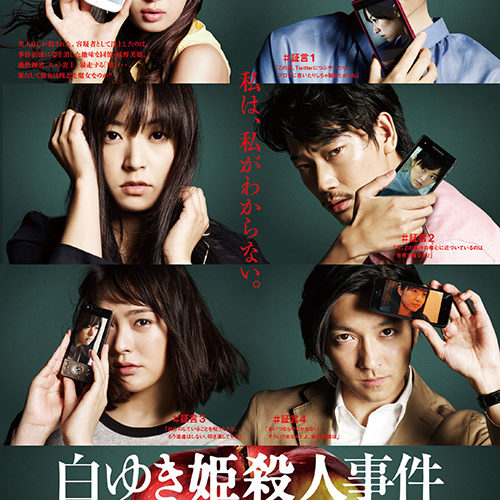

This is what happens with local food blogger Yuji Akahoshi (Gô Ayano). Waiting for his big break as a news director by publishing short, impersonal reviews of the day’s ramen under Twitter handle “Red Star”, Miki’s murder—of which he for all intents and purposes is unaware—precipitates a call from his acquaintance Risako (Misako Renbutsu). Just interviewed by the police due to her being partnered with the deceased at the Snow White Soap Company, she can’t wait to dish gossip with her sole media-connected friend. Yuji sees this “inside information” as his shot for fame, tweeting thinly veiled details to his followers without permission while also hatching a plan to solve the case himself before the cops can. Through hearsay and multiple uninformed hypotheses, mousy Miki Shirono (Mao Inoue) becomes his prime suspect.

Director Yoshihiro Nakamura presents this all as his own quasi-documentary with title cards on every interviewee describing his/her connection with the murdered woman. Inside his construction then lies the manipulative pieces Yuji edits for the news, the actual interview source material he shoots, and first-hand accounts from those involved that can’t help but differ from each other due to our minds’ penchant for fudging details or the inevitability some are lying. These layers of “truths” pile up on top of each other until the actual truth proves inconsequential in lieu of the witch-hunt manufactured. Yuji drags Shirono’s name through the mud, the public simultaneously applauds and derides him for doing so, and those close to her quickly choose sides. Coworkers serve her on a plate; friends declare her innocence; and parents lament their role in creating a monster.

The film spirals into factual overload as a result while its bloated two-plus hour runtime sadly drags due to the sheer number of people wanting to get involved. Nakamura and Minato utilize this excess to show how such a case will escalate—those giving evidence gathering statements shying away from revealing their identities to the fame-whores looking for TV exposure to the authentic character witnesses unable to stay silent while an entire country drags someone they know and love over the coals—but I have to wonder if one or two could have been excised or combined for brevity. It is fun to watch each person’s memory play out onscreen, though, for us to process differences as we conduct our own case in the theater. We join the speculation party forgetting that the police have been absent this whole time.

Yuji being a punk kid making the situation worse by publically sharing stories he’s done nothing to corroborate slips our mind. His cobbled together story—the one that will get his segment on TV—is all we see just like in real life while the police keep things close to their vests so everything doesn’t get out of control. The media is thus given carte blanche to flood the airwaves with their bottomless abyss of strangers’ opinions: “witnesses” like coworker Mi-Chan (Erena Ono) or supposed boyfriend Shinoyama (Nobuaki Kaneko) telling versions that keep their lives intact. We eat it all up because we still believe the “news” is news when we know it’s anything but. The first version of the story we hear ultimately shaping our opinion despite knowing it’s often farthest from the truth.

The Snow White Murder Case plays on Friday, July 11th during NYAFF’s Japan Cuts.