Sometimes foreign language films simply exist across an insurmountable cultural divide that renders them indecipherable here. Hitoshi Matsumoto‘s Saya-zamurai [Scabbard Samurai] perfectly exemplifies through an obtusely-constructed first third before hitting its stride. Comically uneven at the start, I was left scratching my head and wondering if I was missing the joke. An old, toothless samurai with an empty scabbard breathlessly and wordlessly runs through the Japanese countryside with his young daughter following closely behind as three assassins – introduced in freeze-frame – arrive to inflict what should be mortal wounds. The attacks excise the would-be killer and victim from their backgrounds, placing them on black as bright red spurts forth from the aging relic’s body in slomotion. The samurai wails in pain, the girl heals him with a special herb, and it all happens again.

This prologue quickly instills a fear that the rest will end up a long and arduous journey with minimal laughter only coming on behalf of poor production rather than its witty script. Interest wanes even further when we discover the old man is wanted for treason after losing his sword and deserting his Ika clan brethren. Kanjuro Nomi (Takaaki Nomi) may survive these initial attempts on his life, but they are only the first challenges he will face. Captured by soldiers from the eccentric Tako clan, their lord (Jun Kunimura) sentences him to participate in the infamous 30-Day feat rather than perform seppuku – the ritual suicide of disgraced samurai – right away. If he is able to make the lord’s grieving son smile for the first time since his mother’s death, Nomi will be set free.

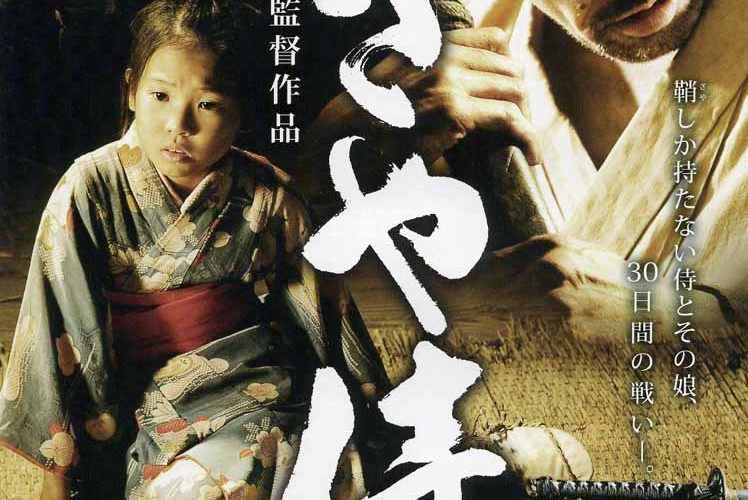

Being the thirteenth prisoner to attempt the challenge and having his ashamed daughter Tae (Sea Kumada) beg him to kill himself presently for the embarrassment he’s caused wandering without his sword, luck does not appear plentiful. When the first performance commences with Nomi donning orange peels for eyes before a drumbeat sounds once the clan’s angry retainer (Masatô Ibu) declares failure after gazing towards the Prince’s emotionless face, it appears all luck has left us as well. For about twenty minutes we’re made to watch attempt after attempt result in no change as the exercise in futility makes Tae and us shake our heads in disbelief. Does Scabbard Samurai literally go through each day, monotonously repeating itself for a 103-minute eternity? I shuddered to think it possible and desperately wondered if I should just give up.

But something changes. The slow pacing; odd introduction of zany characters with little purpose – assassins Oryuu the Shamisen Player (Ryô), Pakyun (Rolly), and Gori Gori (Zen-Nosuke Fukkin); and schizophrenic tone moving from broadly comic to earnestly serious makes way for an underdog tale I surprisingly found myself caring about. Nomi’s guards, first appearing to be a stereotypically underused, jaded veteran (Itsuji Itao‘s Kuranosuke) and simpleton rookie (Tokio Emoto‘s mouth-breather Heikichi), become integral supporters to his cause. Hatching new, unique comedy bits that will hopefully crack a smile from the Prince, they form a bond with their prisoner beyond the selfish desire of retaining their own heads through protecting him for the month’s duration. The lord wants his boy to laugh again, so they must ensure Nomi survives to keep that possibility alive.

By tricking a defeated Tae into seeing her father as a samurai and not the wuss she so easily loves to label him, Kuranosuke morphs into a sort of guardian angel. Nomi’s skits improve as lamely uninspired gags like the “Stomach Dance” evolve into the genuinely funny “Bodyprint”, “Solo Sumo” and “Human Fireworks.” The comedy settles in as Matsumoto ceases to display the proceedings as a boring series of failures ending with the same declaration from Ibu. We’re shown the goofy pratfalls of daily preparations, catch glimpses of the lord warming towards his prisoner’s heartfelt attempts, and join the feudal kingdom’s populace for once allowed to watch and root for the jester themselves. And as everyone starts to believe Nomi can succeed, I finally began to welcome each disparate attempt with a newfound empathy and hope for victory.

Nominated for Rookie of the Year at the 2012 Awards of the Japanese Academy, both Kumada and Nomi shine. Amateur actors performing in their first feature-length film, they commit fully to Matsumoto’s vision and rapidly win you over even when the work itself cannot. Kumada plays Tae as a headstrong girl beyond her years, one who has coped with a similar situation as the Prince in the exact opposite way. Teaming with Itao and Emoto, this trio of cheerleaders and coaches work brilliantly together as emotions run high and time runs out. But while they possess dialogue to act with, Nomi’s physical, comedic performance becomes Scabbard Samurai‘s true highlight. Dealing with his own deep pain, why he gave up his sword and why he is unable to conjure a smile will be explained. A man of pride and honor, however, forfeit is never an option.

The jarring comic relief by Ryô, Rolly, and Fukkin merely pads the runtime of Nomi and Tae’s powerful tale about sacrifice and overcoming tragedy. With a fantastic conclusion thematically taking us to a place no family-friendly American film would ever have the guts to go, Scabbard Samurai goes to great lengths for us to forgive its initial shortcomings. A morality tale instilling ideas of love and honor in death, the beautiful song sending us towards the end credits helps portray a bright future of clean consciences and joyful adulation resulting from Nomi’s example. Set on a mission to revitalize a young boy, his own journey towards enlightenment opens the hearts of all lucky enough to witness his struggle. Through this delightful comedy of errors we witness the miracle of laughter and rejoice at its wimpy samurai’s quiet epiphany.