Not that time stopped, of course. Nor is there interest in a kind of grand-standing disrespect towards whatever worthwhile cinema fit into the narrow 12-month window that just passed (gentle reminder: this is how I make a living) when I say my sense of the landscape has flattened: those well-honed patterns part and parcel of a cinematic year—festival announcements, festival reviews, acquisition news, established release dates, after-work press screenings preceded by shitty midtown food, preferred theaters, weekend subway trips—vanished, the few standing traditions (if “bugging publicists for links” meets the definition) oddly extraneous. A combination of streaming services, downloading out-of-print holy grails, Plex—an app that streams files from computer to TV as simply as if watching Netflix, leaving cumbersome HDMI plug-ins a thing of the past—and finding myself freed from sundry exhaustions of the old world are the best thing that’ve happened to my cinephilia in years. (I am first to acknowledge this, in light of all else, as an objectively awful trade.) When anything and everything goes only to my TV, Fire Stick, or computer, for whom would I prioritize new over old? Myself, sure. But I didn’t want to. Compartmentalizing (dare I say rationalizing) a time of fathomless demise, illness, anger, and fear vis-à-vis the art with which it’s associated… as they say, can’t relate.

Desire to take stock will nevertheless persist. Rather than torture myself with days upon days viewing consensus favorites and oddball curios solely to decide if they’re able to land on a list whose order I’ll forget by February, here’s a ten-film selection that defined something or another about 2020—where my cinephilia’s at, where it might go, what I miss, what’s expressed therein that spoke to the current moment (or didn’t), how I’ll remember the days and nights of unease.

The Age of the Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1980)

I did not pretend to understand half its culturally specific symbolism in the moment or remember much plot since my April viewing. (A quick synopsis, “Four Third-World Christs try to stop the American industrialist John Brahms in Glauber Rocha’s experimental film inspired by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s murder,” is basically coherent with my memory.) Pittances, anyway, against the impression of its psychic-shock color scheme or long, long takes telegraphing mental and moral decay. It is the highest compliment when I say this film—à la Querelle, Eyes Wide Shut, or Love Streams before it—could’ve only been made by someone barreling towards death.

Camp de Thiaroye (Ousmane Sembène & Thierno Faty Sow, 1988)

Perhaps the great Senegalese director’s bluntest political broadcast, which isn’t to imply didactic artlessness. Its portrait of a military platoon at rest does more to recall POW pictures (Great Escape, River Kwai, Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) than hangout vibe, building fondness for characters as each situation—some slapstick hilarious—drives us closer to atrocity. Long banned in France for its unforgiving portrait of institutionalized evil, not-so-strangely hard to find in anything above decent quality.

Duvidha (Mani Kaul, 1973)

To run risk of disregarding delicate narrative rhythms (especially in the well-trod ghost-story mold) for superficial appreciation, one of the most purely beautiful films I have ever seen. As deserving of placement as anything herein, though something of a stand-in for Kaul’s filmography—perhaps this year’s biggest discovery and strongest encouragement to never cease exploring.

Let Him Rest in Peace (Yôichi Sai, 1985)

Trods familiar narrative paths—criminal strolls into small town, vengeance is on the brain, romantic complications ensue—so each can be winnowed down until they’re barely visible. Shot after shot is a stunner. ’80s Japanese fashion galore. Literally nothing not to like, making the fact of my being only the 13th person to log it on Letterboxd a slight shame.

Love Torn in a Dream (Raul Rúiz, 2000)

Raul Rúiz was an extraordinary gift: you watch a ton, have still seen just 1/3 of the oeuvre, pick a lesser-known title and discover major 21st-century work. An experiment in individual images as distinct universes, it contains one of the few truly great POV shots; some of the best time-space jumps I’ve ever seen; “gentle” use of early-2000s DV, i.e. stunning textures and movements but not as aesthetic tenets; and an optical effect that made me lean forward trying to understand how it was achieved.

Lucía (Humberto Solás, 1968)

A narrative triumvirate with more formal variance than any one film seems capable of containing: Ophülsian social drama, Hard to Be a God-like action epic (40-plus years before the fact), comedy of mismarriage—total masterpiece left, for decades, in the realm of total obscurity. Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, bolstering its reputation as the single greatest force in film today, restored Lucía to spectacular shape, and it’s now on Blu-ray and the Criterion Channel.

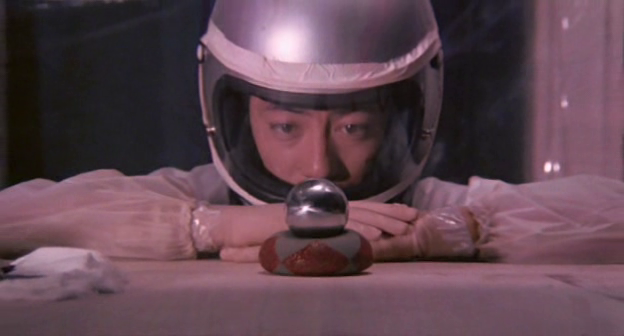

The Man Who Stole the Sun (Kazuhiko Hasegawa, 1979)

You possess an atomic bomb and can hold a city hostage—what next? Here’s a film to suggest we’re far too beaten down by minutiae of the modern world and fear of commitment to enact change more profound than the number of commercials during a baseball game. Though originated from an idea and co-written by Leonard “Brother of Paul” Schrader, this and The Youth Killer, Hasegawa’s only other feature, suggest unique mastery of narrative unfurlment: rarely can something thread solid blocks of tension through a liquid one-thing-leads-to-another framework. In anything like a just world, The Man Who Stole the Sun is mentioned concurrent with benchmarks of Japanese cinema.

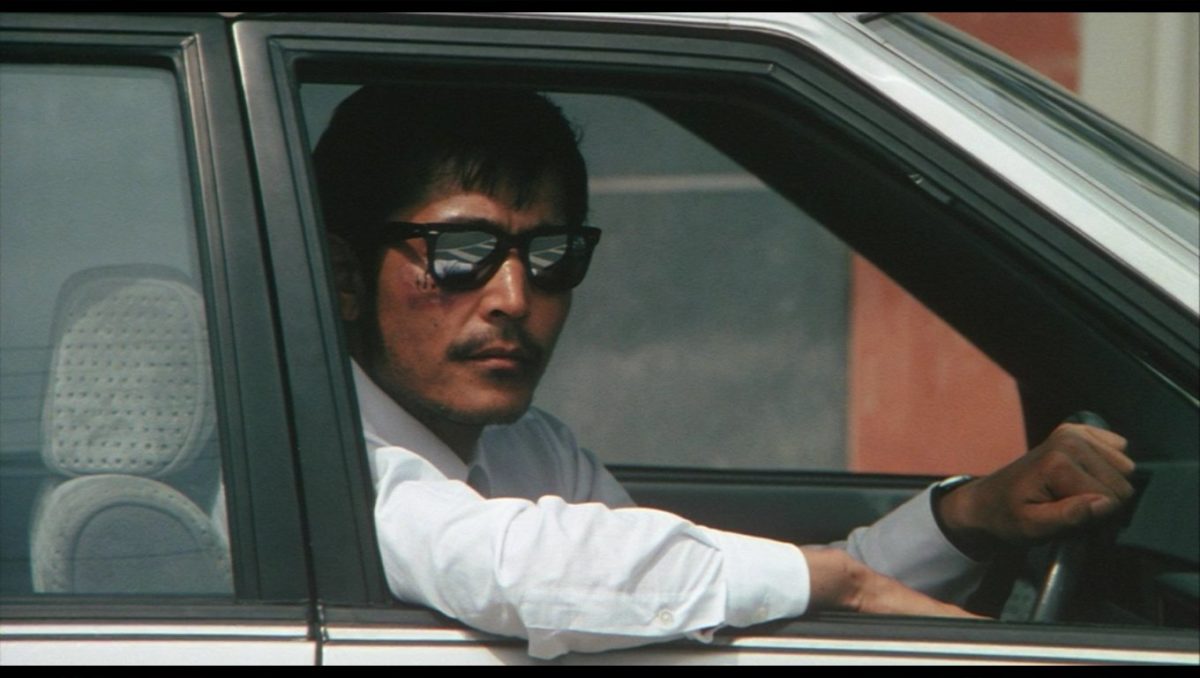

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose (Patrick Tam, 1989)

One’s tempted to rely solely on the above title card as a synecdochical spokesman for qualitative assessment. In any case… the romanticism and action-hero stylings with which we associate Hong Kong cinema (and by which we quite rightly love it) make easy to forget the enthusiasm of its more nihilistic artists to, put plainly, go for it: here’s a gangster-movie love triangle wherein we reach the one logical conclusion of their lifestyle and passions. Tony Leung at his least-appealing and bravest.

Oxhide II (Liu Jiayin, 2009)

Another slow-cinema project devoted to the observance of some specific task (in this case cooking dumplings) initially has a been-there-seen-that air. By the second shot (fifteen or twenty minutes in) do rhythms overtake resistance: each composition, of which there are nine total, answers its previous in manner that’s immensely satisfying for the sense that activity and progress are steadily accumulating, its immersive sound mix the coup de grâce. (Repackage this as dumpling-making ASMR and a hit shall emerge.) That one’s aware of duration without weighing it in quantitative terms may be the final secret of Liu’s genius.

Variety (Bette Gordon, 1983)

Not so certain this is the best American film discovered in 2020, per suggestions of its placement; more arguable that its woman-on-the-street style spoke to the never-shaken longing for an old life more than anything else I saw. But the deeper truth is that this makes for fascinating inside-out viewing, the logical conclusion of a James Benning collaborator trying their hand at plotty (or “plotty”) cinema—how your aural-visual immersion in those places I miss (restaurants, the movies, Yankee Stadium) both stem from and perpetuate narratives we create for ourselves, much as other people (e.g. that businessman who took a fancy to you after visiting the porno theater where you sell tickets) try imposing them on us.