For Franz Kafka, The Castle is about the plight of the individual within oppressive societal customs and the absurd attempt to reach an unattainable. Michael Haneke’s 1997 adaptation stayed faithful to Kafka’s ideas, with voiceover taken directly from the book underscoring the castle’s unchanging distance. That film’s K was a defeatist, not unalike nearly all of Kafka’s protagonists, never really believing he could reach the castle and never being able to question or intimidate those who crossed his path, but Haneke brought his own touch, emphasizing the bureaucratic elements of the story by repeating names of positions, clarifying chain of command, and envisioning the search for a lost record in a blackly comic, needle-in-a-haystack manner. Haneke was examining Austria’s relationship to the European Union, pitting a displaced authority against a village’s xenophobia, which creates an almost conspiratorial method of keeping K from his goal. The fault lies more with the people than the authority, a metaphor for Haneke’s transnational Europeanism.

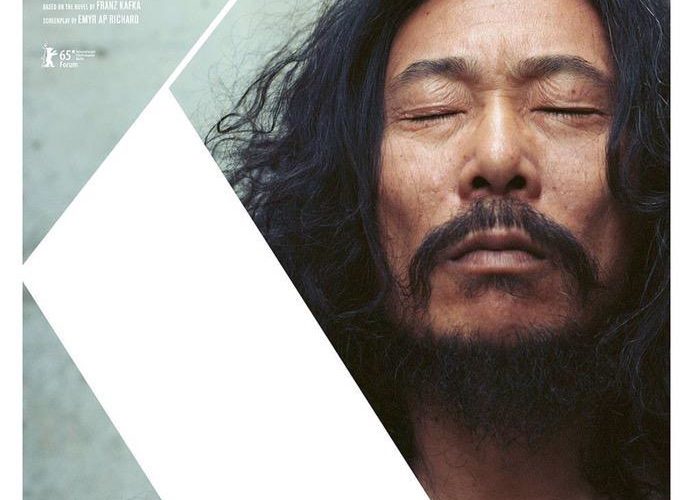

Emyr ap Richard and Erdenibulag Darhad take a different approach, focusing more on the individual than the superstructure, as the title, K rather than The Castle, suggests. Their K (Bayin) is charismatic and confident, determined that the system will rectify the failures of those who delay him and unafraid of confronting those who theoretically have authority over him. Accordingly, the directorial duo (who worked together on The First Aggregate, although Erdenibulag was there credited as “second director”) opens up space dramatically, as in the opening where we see an unconcerned K in longshot walking leisurely through a seemingly barren desert, a far cry from the grueling march through cold and wind that Haneke depicted in tight tracking shots.

As this shot suggests, Emyr and Erdenibulag prefer to let their scenes play out in mobile long takes. In Freida’s first scene, in which she walks through a bar/restaurant cracking a whip to chase off customers while K stays put, the camera follows her through three different rooms before calmly returning to where it started. A man steps in at just that moment looking for K, who is nowhere to be found until a quick cut shows him hiding underneath the bar, alerting Freida to his presence. This world is not the claustrophobic one imagined by Kafka, but a distinctly navigable one full of hiding places and where, as we see later, one-on-one conversations suggest multiple exits or conjure up flashbacks and visions.

But as K goes on, it becomes clear that this open space is not for K to navigate freely, but rather indicative of the ever-expanding web of corruption that encircles him. This clarification comes about through a prolonged series of monologues and some convoluted explanations, but the latter problem can at least be rationalized, even explained outright, as a byproduct of the confusion enveloping K. If, on our first view, everything was clear, the looming threat of betrayal and ever-broadening circles of corruption would lose a degree of believability; it is important that K not fully understand what has happened, and indeed, the final few scenes are abound with his questions.

We also see K move from an impressive geographical transformation to a purposeful and interpretive retelling of Kafka. Barnabas is taking bribes; Artur and Jeremias, rather than betraying K because of his poor treatment of them, were working against him the whole time; concerns shifts from infiltrating the village or the castle to escaping, but each direction that the film’s visual openness suggests contains a trap or pitfall, and so escape to Japan or Russia becomes a pipe dream. When K comes to understand how heavily the deck has been stacked against him the camera stops moving, doors close, and hallways seem too narrow, as if the directors are telling the story purely in spatial terms.

Most surprising, Emyr and Erdenubilag’s film is genuinely romantic; above all, K is about trapped lovers, driven to exploit and distrust one another because of the invisible, only gradually apparent corrupt system. It is a condensed but faithful adaptation of Kafka’s text, but it demonstrates how acting and aesthetic can alter and even reverse an event’s meaning. You would never call it Kafkaesque, but that’s not a bad thing; instead, it’s proof that Emyr and Erdenubilag know how to exploit cinematic means of representation to reinterpret text.

K is currently screening at New Directors/New Films 2015.