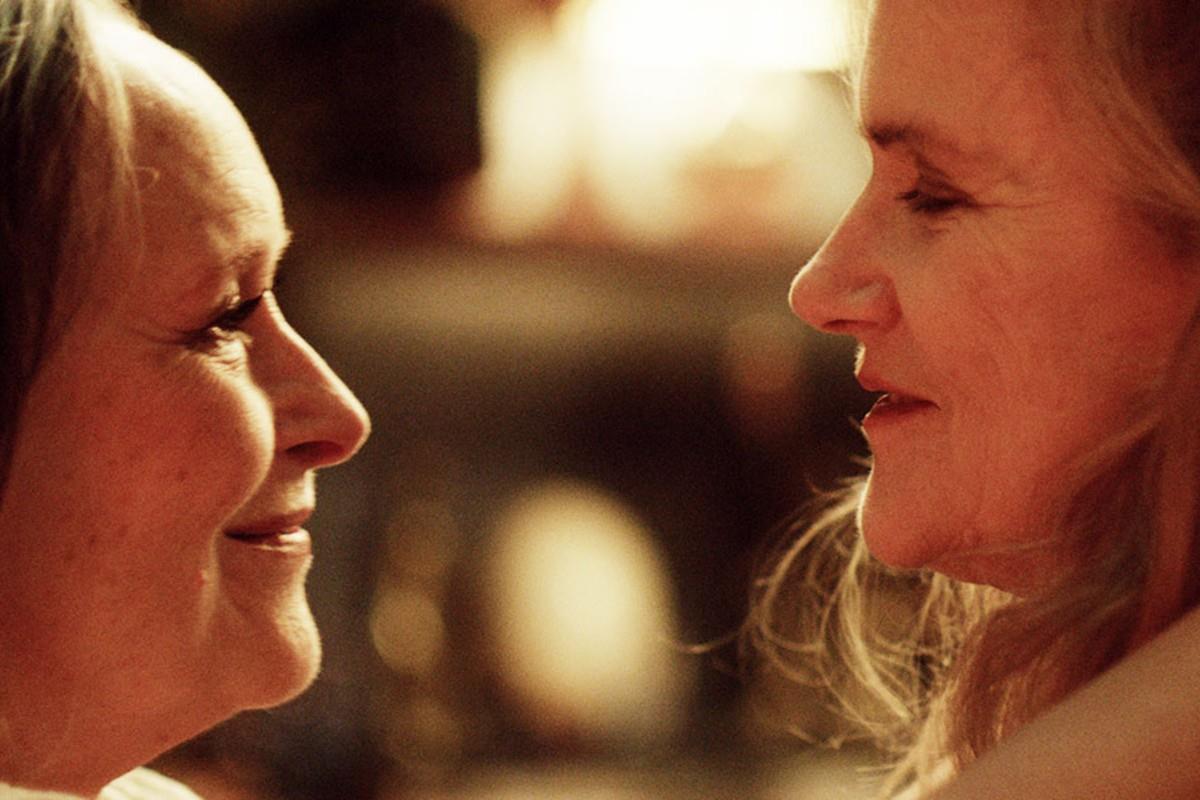

When Two of Us begins, we meet Nina (Barbara Sukowa) and Madeleine (Martine Chevallier) a couple whose comfort with each other is palpable through their silences, a way of intimate communication only developed through years of relationship. As they discuss their plans to relocate from France to Rome while talking about children, we first assume they have always been together, and are finding a way to break the news to the kids. As Nina becomes a bit more impatient, reminding Madeleine she needs to take care of herself as well and that her children are adults, we wonder: is she their stepmom?

It’s not long before we find out, neither of those answers is correct. Nina and Mado, as she is called affectionately, have been having a decades-long passionate affair that remains a secret to everyone but each other. As neighbors living across the hall from each other, one can imagine the romance as it developed. Perhaps one stormy night, the loneliness they’d been protecting each other from gave path to a touch that lingered a little too long. Then some other time a kiss on the cheek landed in the mouth. Year after year of crossing the hall to visit each other at their happiest and at their most desolate, led to romance.

Although we are not granted a flashback sequence to explain how the relationship came to be, its importance is felt in the texture given by director Filippo Meneghetti, who co-wrote the screenplay with Malysone Bovorasmy and Florence Vignon, as they epitomize what the expression “lived in” means.

There is a sense of urgency and history in each moment where Mado and Nina are together. We may be deprived of the exact details of the romance, but they aren’t. This is why it hurts so much when Mado, overcome by Nina’s disappointment in her secrecy out of the fear of how her adult children will react, has a stroke that renders her unable to speak and move. We feel their history turn to a dark new chapter.

Because their relationship has always remained secret, Nina can’t even spend time with Mado while she recovers. There is no place for “a neighbor” during family visit hours. So the film then becomes something peculiar, as Nina tries to reconquer the woman she loves. A woman who might not even recognize her now.

If the sensation of being seen for who we are is remarkable, nothing compares to being seen fully by the person we love. If they see all of us and choose to love us, then there is the possibility of fulfillment, of having a soul mate. Sukowa perfectly combines warmth and fear as she encounters a vessel whose contents are unknown in the silent Mado. She breaks the heart in moments where she pleads to be recognized, as Nina wonders: is this Mado the same who wanted to move to Rome with me?

If the movie focuses on Nina, it’s because in Mado’s absence, she is allowed to fill in the gaps, to discover things about her she never knew. Sukowa is a master at conveying the pain of discovery when there is no one to share our findings with. We see Nina enter Mado’s most private spaces, that Meneghetti avoids any hints of Vertigo obsession is a display of his compassion for his characters.

Although Nina’s journey turns her into a detective, caretaker, and someone who must play the fool, Two of Us avoids unnecessary genre conventions, instead unfolding like a slice of life. The film lies somewhere between Sarah Polley’s Away From Her and Michael Haneke’s Amour. It avoids the crescendo of hope in the former, without falling into Hanekian nihilism.

Meneghetti might be a first-time director, but in his assured pace, his determination not to provide easy answers, and his ability to suggest without manipulating, his career can’t help but look promising. Watching Two of Us in the midst of a global pandemic, where our free movement has been restricted, can’t help but resonate in powerful ways. Like Nina, we too may wonder if love can outlive the pain of sudden, but prolonged separation.

Two of Us screened at New Directors/New Films and opens in Virtual Cinemas on February 5.