Sauvage/Wild opens with a gay hustler in a doctor’s office. As he discusses his ill health—his cough, his odd stomach pains—the camera, like the examiner’s hands, passes carefully over the bruises on his ribcage, his abdomen, down over his groin. Such frank corporeality is familiar from other gay films which seek to expose and honor the wounds society inscribes onto vulnerable bodies—Sauvage’s star, Félix Maritaud, played one of the ACT UP members in 120 BPM—but then the scene shifts gears, becoming not quite a parody, but certainly an affectionate meta-joke on the ways in which the serious-minded and erotic prerogatives of queer cinema elide into each other.

It’s the wittiest moment in a film which frequently falls back on contrived, conventional storytelling at odds its with its body-and-soul immersion into the physical and emotional toll of life on the game. One is left with the nagging suspicion that writer-director Camille Vidal-Naquet began on this scene so he could work in the fact that his protagonist has a cough. You know—a movie cough.

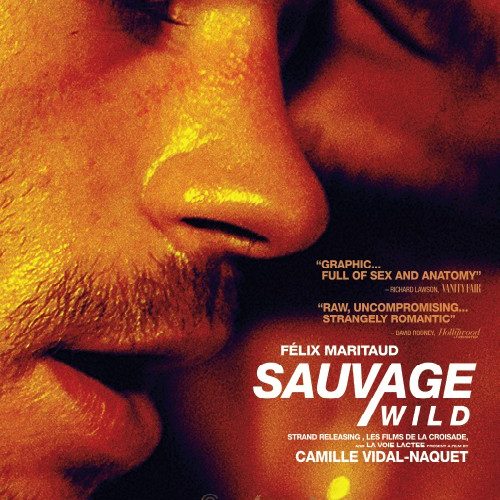

What distinguishes Vidal-Naquet’s first film is the extremes to which he pushes Maritaud, who gives a name-making performance. His hustler—apparently called “Leo,” though only to himself, as we never hear his name—has a great walk, a macho swagger with side-to-side swish, and a 22-year-old body that’s beautiful now but won’t be for long, his youthful musculature revealed, and not yet atrophied, by an erratic diet of stolen apples and crack cocaine. Maritaud’s brute-sensuous brow becomes increasingly sweaty, dirty, pale from Leo’s life of sleeping rough or not at all, never changing clothes, drinking water from puddles on the street; moment-to-moment, the actor always seems present, ardent even.

Leo is, per the title, “wild,” living and loving freely and instinctually (to the point that he may be functionally illiterate—hardly the film’s only instance of gilding the lily). He’s told that he’s too open in thirst for intimacy, not savvy or pragmatic enough to avoid getting hurt in transactional relationships—told this by Ahd (Éric Bernard), another of the hustlers who slouch every night around one of Strasbourg’s parks, eyeing the cars as they crawl past. Leo is in love with Ahd, with his boxer’s bullish shoulders and superhero-costume abs; Ahd advises Leo to shack up with an old guy who’ll take care of him. Despite Ahd’s denial—“Think I’ll suck dicks forever? I’m not even a fag”—you are what you do; Sauvage dramatizes the way sexual identity, no less than any other aspect of identity, is subject to market forces.

Vidal-Naquet shows us Leo’s encounters with an old widower, a man in a wheelchair, and a chubby aging mama’s-boy party boy; we see gym-toned and sagging flesh, poppers and lube; we learn a little a bit about the many micro-negotiations and maneuverings within the course of a single encounter, such as whether or not to kiss (Leo, going with the flow, will; Ahd asks for more money). And yet: Why are all the pickups shot with telephotos? We hear nothing of the initial approach between john and trade, only see it from a camera that suddenly absents itself from the scene, becomes furtive and voyeuristic. There’s plenty in this film that still feels like guesswork—no points for predicting that Vidal-Naquet would shoot a party through a smoky, golden haze, or a discotheque though flashing blue-steel strobes—and the generic scope of the drama makes the film’s explicitness seem less like an open-ended view of the lesser-filmed precincts of gay desire and irreducible complexity of real bodies in action, and more like misdirection. Sauvage schemes an obligatory cross-section of vignettes into a exoticizing parade-of-horrors: one john gets ripped off; another is a well-groomed man, said to be into “blood and torture,” who cruises by in a luxury car like an angel of death. (He’s called “The Pianist,” presumably because of the piano music wafting ominously out of his sound system.)

Leo’s on-screen bottoming-out, as it were, involves, how to say this, a butt plug the size of which I am not remotely desensitized to, in a scene with a creepy, decadent couple (Leo’s only nonwhite clients). It’s rare and insightful for a film to think about the way consent can function, or not, within sex work—to attempt to diagnose the asymmetries of power and potential for exploitation. But it’s maybe also worth questioning the calculation to manufacture empathy for a gay sex worker by invoking and stoking straight-baiting panic over anal sex.

The romantic, condescending, Othering gloss the film’s title of casts over Leo—its savage innocent, its wild child—is cemented by the three successive endings, each worse than the last. In turn, Leo is doomed, redeemed by bourgeois monogamy, and beatifically feral. The role is more concept than character—albeit one that Vidal-Naquet and Maritaud make viscerally alive.

Sauvage/Wild plays at New Directors/New Films 2019 and opens on April 10.