As much as we’d love to believe certain myths, no filmmaker has simply waltzed into making a masterpiece without cutting their teeth beforehand. Jaws may have been the first modern blockbuster, but Spielberg had already created a terrifying beast with the mechanical semi-truck in a made-for-television film, Duel. Truffaut’s The 400 Blows remains among the more towering feature debuts, but the filmmaker had three shorts and countless pieces of criticism to prepare him. And The Passion of Joan of Arc has perhaps become silent cinema’s greatest achievement, but its director, Carl Theodor Dreyer, had to work his way toward creating such a vision of the spirit. The Danish master made eight previous features, and to study them is not to just see a director finding a cinematic voice, but to experience highly complex approaches to material that might otherwise be ignored.

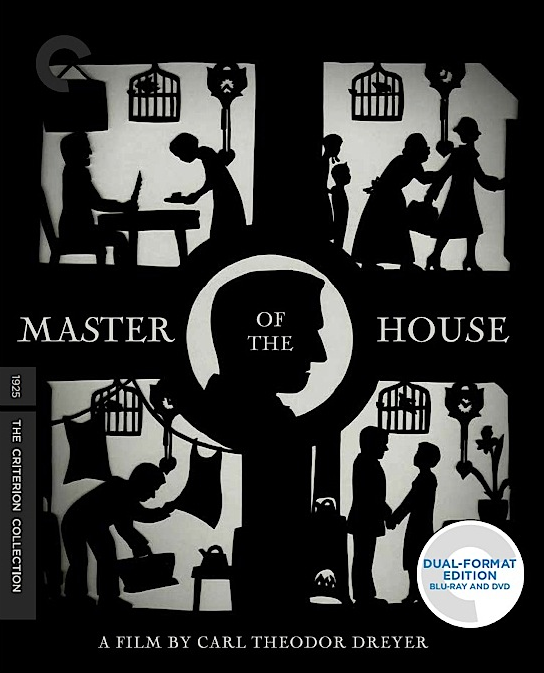

Master of the House might seem like a curious choice for The Criterion Collection, which has put the film out in a gorgeous Blu-ray, as even Dreyer enthusiasts often point to fellow pre-Joan silents like Michael and The Parson’s Widow as more canonical works. But House provides a Rosetta Stone for the experimentation this director was developing through the 1920s, taking a familiar story and imbuing it with a strong psychological bent that cleanly breaks down any archetypal judgment.

Based on a play by Svend Rindom, “Though Shalt Honor Thy Wife,” Masters of the House contains most of its action within a single boarding-room apartment. As Danish film scholars have noted, this form of interior drama dealing with domestic strife — a genre known as the kammerspielfilm, or “Chamber Play” — was common throughout European cinema. But most directors worked within the tableau staging — flat, deep-focus shots that relied on character movement more than cutting to drive plot development. Having studied D.W. Griffith’s films, Dreyer believed in editing as much as staging; Master of the House thus features over 1100 cuts — not just an unusual amount for any film of the time, but especially an intimate drama.

Cutting is not a virtue in and of itself, of course, but each of Dreyer’s cuts serve both a spatial and psychological motivation (a tactic David Bordwell explains quite beautifully in his exquisite video essay provided on the disc). Master begins as Ida and her daughter, Karen, move about the small house, preparing the room for her husband, Viktor, to arise from his slumber. Instead of creating these various spaces on a 180-degree plane, with the camera always remaining on one side, Dreyer’s room was a three dimensional set with removable walls, complete with working electricity and water. The opening sequence serves three different purposes: to introduce us to the characters moving about; to set the stakes of these tasks in relation to Viktor and his temperament; lastly, and most importantly, to help us learn this space and how it functions. Dreyer uses various props to breed an understanding of how to essentially read the room, whether it’s the stove, the birdcage, the table, or the corner. By having these characters move in and out of each shot and show us where they move into, our minds begin to draw a mental map of the room.

Cutting is not a virtue in and of itself, of course, but each of Dreyer’s cuts serve both a spatial and psychological motivation (a tactic David Bordwell explains quite beautifully in his exquisite video essay provided on the disc). Master begins as Ida and her daughter, Karen, move about the small house, preparing the room for her husband, Viktor, to arise from his slumber. Instead of creating these various spaces on a 180-degree plane, with the camera always remaining on one side, Dreyer’s room was a three dimensional set with removable walls, complete with working electricity and water. The opening sequence serves three different purposes: to introduce us to the characters moving about; to set the stakes of these tasks in relation to Viktor and his temperament; lastly, and most importantly, to help us learn this space and how it functions. Dreyer uses various props to breed an understanding of how to essentially read the room, whether it’s the stove, the birdcage, the table, or the corner. By having these characters move in and out of each shot and show us where they move into, our minds begin to draw a mental map of the room.

This very delicate set-up would be rather pointless unless it was absolutely necessary for Dreyer to employ the camera in a way dependent upon reading this space. Master of the House tells a story that is, in fact, dependent upon a psychological reading of the characters: it follows the torment of Ida under Viktor — the woman is constantly scorned by Viktor for not providing enough, but because he has provided so much for her in the past (a tricky narrative development the director uses to complicate the action), she cannot bear to leave him. Soon enough, Viktor’s former wet nurse decides to have Ida flee the scene of the crime and take over as “master of the house,” creating a series of comic annoyances until Viktor realizes the necessity for Ida in his life. Like The Passion of Joan of Arc, Dreyer’s camera often skewers our sense of the space to engender a psychological reading of the characters. This is most apparent in his use of the iris technique in almost every shot, eliminating unnecessary information and making us focus on the characters and their faces. As we get a series of shots between Viktor and his wet nurse, Dreyer creates the sense of a duel of wits. Emphasizing the sneaky looks on the wet nurse’s face, he creates a comic playfulness between the two characters that slowly portrays the older, smaller creature as the dominate ruler.

Master of the House is certainly less ambitious than the director’s later sound works, but even in this marriage comedy can we see his interest in resurrection and redemption. Late in the film, Dreyer finds Viktor at his most humble moment, the camera close enough to his face you can see the tears beginning to form (his test run, for Maria Falconetti). Dreyer then uses the complexity of the space to sneak Ida around the house while Viktor remains completely ignorant, so she can observe her husband’s reformed behavior. When the man is reduced to his most child-like and put in the corner, their reunion takes on the properties of a resurrection, the comic and the transcendent melded into one. By the end, Dreyer now uses the reverse side of the dinner table to unite his family together; where Viktor once turned his back against others, he now commands with an open heart.

Is it obvious from Master of the House that Dreyer would become one of the greats? Only in parts—for as much as his innovative camera style defines this domestic drama, the film’s characterization and narrative structure often feel indebted to older structures which the director would abandon in a few years. If one were to truly dig into the history of Danish melodrama, other artists surely began radically experimental in film style as well, only to be lost to either time or poor archive. But Master of the House is a reminder that even the most simple of stories require care, and if we begin to look at how we read the building blocks of cinema, we can identify truly great art.

Master of the House is now available on The Criterion Collection.