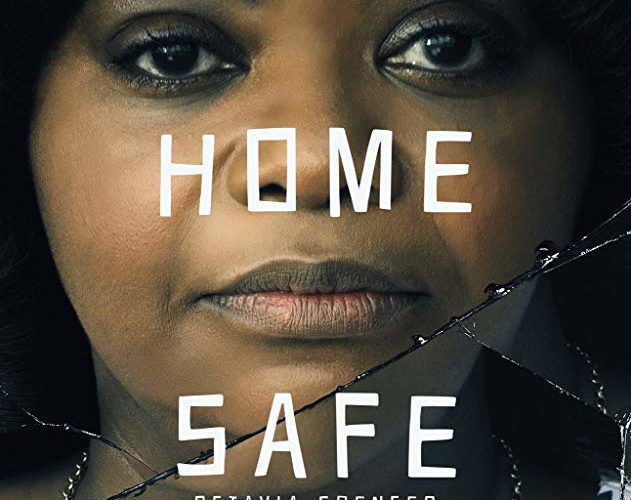

High school can be hell. Between peer pressures and hormones, it’s a hotbed for drama, and it’s no wonder films about teenagers remain ripe for the big screen. Some directors build entire careers upon humanizing the teenage experience, but for every Fast Times at Ridgemont High, She’s All That, and American Graffiti, darker visions exist. Tate Taylor’s Ma is a film about high school in a different vein than Olivia Wilde’s Booksmart or Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird. It’s a bold mutation of the subgenre—a truth or consequences version that shines a light on cross-generational cause and effect. It’s also a strange, wild, messy, and uneven film that stands out as a completely balls-to-the-wall bonkers studio release. Octavia Spencer is a powerhouse from the get-go, yet I only wish the film recognized its potential to flesh out its compelling foundation.

Within its small-town setting, Ma unfolds like a teen comedy and introduces its adolescent protagonists, with Taylor quieting our nerves and wisely subverting expectations. I never believed that hard-drinking mean girl Haley (McKaley Miller) would hang with sensitive Andy (Corey Fogelmanis) or that this group would sidle up to Maggie, (Diana Silvers) the doe-eyed newcomer in overalls, to offer phone numbers and party plans. But in a film boasting numerous WTF moments a minute, this barely registers. More stunning is the missed opportunity when cinematographer Christina Voros captures Maggie standing behind a glass wall, staring at the student body in the cafeteria. Had the film used this image to initiate parallels between Maggie and the film’s antagonist, Ma would feel richer and its climax more poignant, but it’s one of many missed moments amongst the scattered shlock.

When Maggie is tasked with finding an adult to purchase alcohol for them, she approaches Sue Ann (Spencer) who begrudgingly agrees, and after noticing the name on their van, begins stalking the teens on social media. Even before mood swings and attachment disorders rear their heads, Sue Ann is an odd bird—adept at investigation and observation but so grumpy and prone to blank stares it’s a wonder the town veterinarian (Alison Janney) keeps her as the vet tech. Sue Ann offers the teens her basement as a place to celebrate. Her only rules are sober driving, clean language, no going upstairs, and to be referred to as ‘Ma.’ The offer is eagerly accepted by the group; only Darrell (Dante Brown) looks uneasily upon Sue Ann’s isolated home. Before long, new friendships trigger the nebulous psychological mess within Sue Ann. Her desire to connect takes a sinister turn, a scabbed-over blister lifting underneath her surface.

The film and its sympathies hinge on Spencer’s emotional palette. The sweetness and tart sarcasm seen in The Help and Hidden Figures are used to offset her character’s volatility. Taylor captures close-ups of her large eyes flickering with sadness and hopeful smile curling into rage. Her performance reflects the same audience fears as that of Kathy Bates’ Oscar-winning turn in 1990’s Misery. The film’s thematic vigor, as well as Sue Ann’s fixations, lie within a past that cannot be changed–only dealt with. We eventually learn what transformed Sue Ann into the creature of today and although we understand her humiliation, Taylor could have gone deeper within the context of its time and place to make Sue Ann’s experience and subsequent PTSD more shocking. The film illustrates karma’s option to return in packages that hurt not us, but those we love. Unfortunately, it revels so deeply in camp that its message ultimately becomes lost.

While Ma mostly melds well from quasi-comedy into horror while keeping viewers on edge, it continually fails to investigate its most interesting ideas. By the time the Munchausen by proxy (!) angle came to pass, it was clear Ma had zero intention in tying its ends together. Its adult characters (and flashback versions) feel one-dimensional which makes it difficult to care about them. Ma would have stung harder had its supporting cast or pure archetypes felt like real people rather than simply there to trigger the three-dimensional Sue Ann. A clumsy apology comes late and given the character’s good heart, it makes zero sense that this wasn’t provided earlier. We needed to know more about Sue Ann’s life as a teenager, her family, and a few glimpses of day-to-day living to more coherently understand her psychological issues and the twists that the movie hinges upon.

The peculiar revenge options doled out make Ma an entertaining experience, but the film never truly earns Spencer’s stand-out lead performance. Her antagonist unfolds rather than explodes which begs the question: do we have a right to complain about consequences if we’ve helped create the monster? It’s an idea Taylor continually toys with through Ma without ever giving a convincing answer.

Ma is now in wide release.