It’s been years since a demonic entity has seen the woman it loves—she who conjured it to the surface before being driven out from the place in which she did. Tonight was a chance reunion wherein familiarity was quickly replaced by violence before a yet-unseen escape sees both parties going their separate ways. The woman stumbles towards a virtually deserted police station while the force of evil seeks out someone else who might be able to help it confront her within an environment it can control. So as Luz Carrara (Luana Velis) blasphemes God in Spanish via a distorted prayer to the two German detectives assigned to her, Nora Vanderkurt (Julia Riedler) solicits Dr. Rossini (Jan Bluthardt) at a bar with a tale of her girlfriend’s woe.

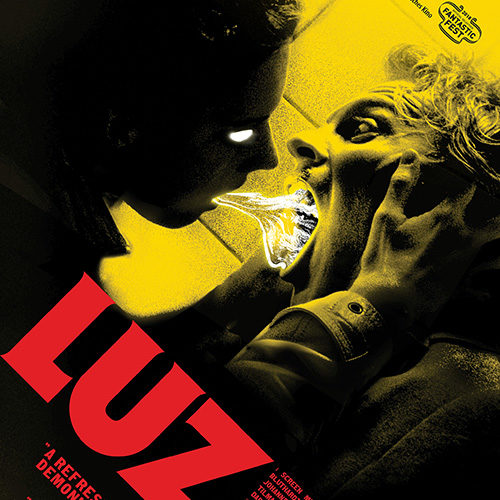

Shot on 16mm with its grain and blemishes left intact to augment the diffused clarity of its film stock, first-time feature writer/director Tilman Singer very meticulously crafts a disquieting atmosphere through aesthetic from frame one with Simon Waskow’s score permeating our auditory channels as the characters interact with cryptic intentions. Titled Luz after the object of affection at its core, Singer intentionally positions the demon as our entry point instead since the film is more concerned by its desire to take her body than her yearning to elude its grasp. It’s therefore only a matter of time before Nora and Rossini make their way towards her destination, the police unwittingly granting them access to come in and prime her for the kiss that should render them inseparable.

So despite our intrigue rising at the weirdly eccentric machinations of Luz chanting nonsense to Detectives Bertillon (Nadja Stübiger) and Olarte (Johannes Benecke) and Nora shrewdly plying Rossini with drinks until his pager goes off with an emergency code that she must now assist him in completing, the real fun occurs in a conference room doubling as interrogation suite where the rest of the film will take place. It’s here that Olarte sets up some chairs alongside a microphone-stand doubling as rearview mirror holder for Luz to reside under hypnosis near the doctor to reenact her evening. Rossini thus becomes a guide through her memories with Olarte translating Luz’s Spanish for the others to understand. She soon believes she’s back in her taxi picking up an old friend.

What you must remember, however, is that a malicious force is orchestrating everything by taking over the faces and abilities of those it uses as stepping-stones towards its love. As such, the blur of past and present (objects and people manifesting inside the conference room as though Luz is back on the street) is accompanied by a blur of identities. Because the demon has infiltrated more than one character (including one from the past in Lilli Lorenz’s Margarita), the strobe effect constantly shifting our setting is promptly outdone by the one altering whom it is populating the screen. Eventually fog descends indoors until one actor leaving the frame means another enters in his/her stead. Does Rossini speak to Luz as a doctor or the mysterious Nora?

Singer presses the accelerator to the floor the moment Luz goes under Rossini’s influence. Things initially seem calm and authentic until Bertillon’s use of a walkie-talkie to relay what she’s learned begins to irk the doctor because of its affect on his patient’s sense of place. So as we move forward to the point of escape when Luz and Nora departed to where we first met them (police station and bar respectively), tensions rise until the impossible is made visible and the demon presents itself removed from artifice to commence its plan to earn back its love’s trust. The result is a whirlwind of activity with quick cuts disorienting our view until each layer of truth and deception overlap to the point where one stops being discernable from the next.

It’s a sensory feat of nightmarish mood that doesn’t demand a more robust plot to supply it purpose beyond the experiential. All you need to know is that this demon will stop at nothing to get to Luz and that everyone in its way will be utilized as tools to do so. Watching a prologue depicting the moment she conjured it with the help of a candlelit circle of salt would only slow things down and hinder the filmmaker’s desire to keep us off-balance when the later merging of flashback, reality, and perception achieves exactly that while still providing the context necessary to understand the relationships at work. It would have also made the ritual itself more important than the players—something we learn early on as false.

That might seem a tiny detail, but it gives the whole credence by letting the demon become more than a ghost. Letting this force explain how the ritual doesn’t matter beyond its facilitation of the conjurer’s capacity to believe goes a long way towards imbuing it with longing and purpose. This flip in vantage from the films that obviously inspired Singer lets his become its own monster because we’re asked to be in the demon’s corner here. We admire its ability to recruit new vessels and warp reality to its whims with nothing but its victim’s mind at its disposal. That everything occurs in a single room is conceptually wild enough to earn a second viewing. Its effective visceral hold on our imagination guarantees its inevitable cult status.

Luz hits limited release in NYC and LA on July 19.