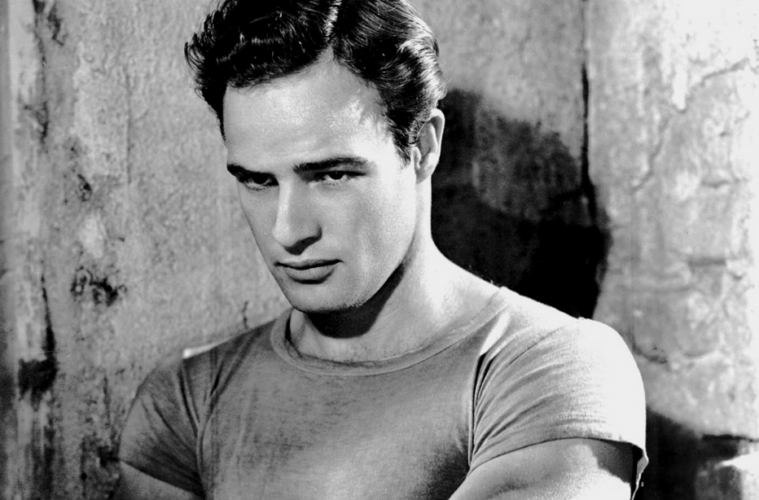

Given access to hundreds of hours worth of previously-concealed audio interviews/musings with Marlon Brando, director Stevan Riley magnificently produces one of the best documentaries about a legendary figure — all without a single talking head in Listen to Me Marlon, as I noted from Sundance this year.. Ahead of his time, we begin with Brando predicting the future of filmmaking: actors will soon be motion-captured and their essence created in a computer screen for projection. We then witness the man resurrected through such a digital form, incorporating the audio from his interviews, giving an ethereal effect interspersed throughout the film.

I recently had the chance to speak with Riley for an in-depth conversation regarding the technical process of creating the documentary, the legacy and enigma of the actor, how he’s pushing the boundaries of documentary, being inspired by Radiohead, the theatrical vs. television experience, and much more. Check out the full conversation below.

Much has been discussed about the 300 hours of audiotapes that were used. From an editorial perspective, was it already organized or did you have to go through chronologically or thematically?

Yeah, it actually wasn’t 300 hours at the outset. The way the project involved, in fact, was that I was more interested in the story and I wanted to do something original. We had access to all the archives at the estate and so the question was, what do you they have exactly. But they were just unpacking this stuff at the time. So a lot of the archive was in boxes in fact. It had been stored for ten years. So even during the edit – and the edit was nine months – there was stuff coming out of boxes and even towards the very end there would be ten tapes I would get.

So it was very interesting how it involved, in a way. I was actually terrified at the beginning because I had kind of committed to this route of telling it all in Marlon’s own words after just listen to six or seven tapes that were initially available and were just being digitized. But there was no clue that it was ever going to be possible to tell it all in his own words at that point. I had actually went out to the states to do research but also figure out, if I can’t tell it all in his own words, who would I possible include in the film? Who would I interview? It was only the further that things developed that I became more and more convinced I should go with plan A because it would actually be less confusing. There were so many people in his life who were only in touch with him for brief periods, maybe a few years. He might pick up a friendship, drop a friendship.

Anyway, just to mention that, but then in terms of organizing it, I did a fair bit of pre-production. I did the initially proposal, which it currently has the title Listen to Me Marlon but it was Brando on Brando and when that was commissioned I turned it into more fully formed shooting script. That shooting script helped inform how I’d go through the transcript. When all the tapes were transcribed, they were in these big, thick folders. There was twelve of them so they came several feet off the ground. I’d just go through with a highlighter and then just go through every page and write in the margins, tiny little one or two word captions, I’d call them, that would conform to different story points. And then the story points I arranged in a grid and then brought them into the edit in different sequences. Then those were movable parts that could then be constructed into scenes, If that makes sense.

Yes, that’s fascinating. In my review I said it almost feels like you’re watching a final performance from Marlon Brando. We’re never going to see another movie with him, so this feels like a send-off in a way. Did you feel that pressure as you were making it or was it more when you saw the final product, if at all?

Even from the opening section, where he talks about how actors are not going to be real, they’re going to be inside a computer, then that soliloquy from Shakespeare. I felt like he was delivering on his prophecy and that was his performance in a sense. When that 3D scan was done of his head, I got an actor in to lip-sync his lines and film it from different angles so I could switch those up in the digitization of the head. It was a performance in a regard – the inflection, the turn of the head. It had to really try and look like Brando. So there was a bit of that. Certainly for those sections and then even if wasn’t a performance, it was certainly a kind of right of reply. I was representing his life. Of course, he did a post-mortem on his life by himself, but he’s also going to bring on his character in a way that people that might wouldn’t otherwise know because all they’ve been fed through the course of his life was that media representation, that tabloid myth of Brando, it was performance in a sense and also this right of reply, a last word.

You spoke about the digitized version of Brando and the motion capture that he saw. We’re seeing it come to fruition in films like The Congress and James Cameron’s work. When you came across his speaking to that, did you know immediately you were going to use it at the beginning as this ethereal opening?

Yeah, I was already racking my brain to thinking what kind of device… bear in my mind, the edit was all pretty much, largely black screen. It was audio and music. I was just trying to get the story down first and the mood and the tone of it. I was always thinking about visuals. It was always this press question: what the hell am I going to cover this with all the way through? I had a rough idea it would be a third archive, a third movie (his films), and then a third re-con. Re-constructing the house and rebuilding this “house of pain,” the media dubbed it, but also this house being the inner workings of his mind as well, a metaphor for his brain, for this inquiry and his own thought space. I thought it would be nice to have some kind of presence of Brando in the film, that third-person presence of him looking back on his life. Of course that possible by trying to make the house alive, by putting wind through the curtain or having candles or smoke – just this sense of presence, that it was a living space and there was somebody in the home was going to do it.

Then I toyed with the idea of if you could involve an actor, but that was never going to work. No one could play Brando and then I heard about this 3D scan that he’d done from one of the guys who works at the archive and I just latched on to that immediately, just thinking where is it, what could I do. I thought straight away about the possibilities of bringing that to life. We had his head, what could be done? When we finally got access to it – it took about six months to actually track it down, assemble it, decode it because it was very old software, and then do the creative to bring it to life. There was actually enough detail in the scans to do enough facial representation down to his skin pores. It was super high-resolution. There was several scans. He did all of these different expressions, then what you could do with interplay with this software. It was fine though, because I didn’t want it to be photographic or photo-real because I wanted to be this ghost in the machine, kind of fragmented, digitized being that was searching for meaning. I’d seen Radiohead’s House of Cards music promo.

Oh, yes.

Yeah. I was thinking something that might approximate to that. That was my creative reference in my own head about where to go with it. The it was a case of bringing it to life with an actor and doing that motion capture with this actor lip-syncing and, as I said, filming it from different angles to try and get that recreation.

You spoke about the footage you used from his actual films. There’s a few sections, whether it’s A Streetcar Named Desire or when you show his character’s death in The Godfather, and you overlay his audio discussing death and the meaning of life. It’s this two-handed emotional punch because we all have memories of watching those films for the first time coupled with the emotional weight of his recordings. How early did you think about which films would be well-represented and did you re-visit his filmography?

Yeah, well, I discovered a lot of them as well, really. I had seen a lot of Brando’s films but I hadn’t realized he starred in 39 or 40. It was a lot to watch, in fact. I was just figuring those out along the way. I was also how much life was imitating art and vice-versa. Brando would bring all the things he’s interested in to a part and try and smuggle them into his character. He’d bend it to almost convey his message and there was many things which he was fascinated by and the film looks into about the nature of technology and good and evil and all these things that occupied him – and there were quite a lot through the course of his life. It took from the light to the dark and from truth to lies. That is when he was oscillating through a lot of his life. So, yes, some of those parts really resonated and explained those things that had fascinated him better than others.

The Godfather had its own resonance and Streetcar was great, again, for exploring that idea of the myth of cinema and in Apocalypse Now you see the myth of America that he explores. All these things corrupt our view of the truth or we lose touch with reality and then people were losing touch with who Marlon Brando was and it was becoming a myth of himself. Then Streetcar was emblematic in so far it was his exploration of the method and how he had to relive his childhood every evening when he was playing Stanley Kowalski on stage and he was trying to channel his father’s anger and rage. It was also nice using the film clips not just for their own sake, not just popping [them in], oh it’s just Brando playing a character, but to actually to get inside his head and use the clip from the film to be woven into his first-person narrative and make sure those were tidy scenes between those because they did overlap. The thinking and the emotions applied to the real-life and the characters he was playing.

Brando certainly has a specific enigma around him with the fact he didn’t do much press and he was almost like an Orson Welles-type figure in that there were a lot of ups and downs in his life and his career. We obviously don’t the perspective, but it’s rare in Hollywood today for an actor to have that enigma around them because there’s so much that’s publicized, even if they don’t want it to be. Do you think the documentary would be less effective if his life was more public?

Well, yeah, quite possibly. In the end, I don’t know whether his was the best strategy. The more he shut himself away, the more he tried to get away from the press, the more desirable and the rarer he became as this prey for the paparazzi to hunt. It wasn’t his natural inclination to be so private. I think he was actually someone who liked to be out in the world, who liked to be free, who loved to explore, but he didn’t like to be under the microscope. He was a private individual. He didn’t want to share his life. That quote he says, “I don’t want to lay myself at the feet of the American public and let them enter my soul. My soul is a private place.” That was deeply true to him. He didn’t want to just be on public display the whole time, but he was the prized scalp. He was the one the paparazzi wanted more and more and more. The more they chased him, the more he hid away and the more they wanted him. It was a curious dynamic that one.

Who is to say that maybe if he gave more of himself through the course of his life then maybe many of the problems wouldn’t have actually arisen and he wouldn’t have been such popular curiosity and fascination. But the fact that he was so private, and you’re right, he hadn’t given that many interviews through the course of his life. That was interesting as a creative challenge in the beginning of the film in conceiving of an approach and doing this Brando on Brando line and Brando solved that problem for us. Who was the real Brando? Who was the mystery man? Let Brando tell us himself. As I mentioned earlier, there was never any guarantees that that could be delivered on. We didn’t know much he’d said about himself or how much he would be able to deliver on that full story of his life and these different layers of narrative.

In the last few years it feels like directors have found new ways to open up the form of documentaries like The Act of Killing or Leviathan or more specifically focused ones like Amy recently. I would include this documentary in that category as it’s one of the most formally interesting documentaries I’ve seen recently. Does this new boundary pushing of what can be accepted in documentary excite you?

Well, from my own point-of-view I just think that if you dedicate yourself to do a documentary you know it’s going to be at least a year of your life by the time you raise the funding and do the festival circuit, because I actually finished Brando last October. So it’ll be year when it comes out in the U.K. so there’s a lot of your life that goes into it. You better make sure you’re doing something that will interest you and something you can do something original with. I love documentaries, doing them, but anything to get away from the tired old creative devices is always exciting. You can mix it up and tell different ways to tell the story because the talking head is necessary, it’s never going to go away, but there’s way to allow the audience to lose themselves or to really access the character rather than other people telling you about it. With the Brando piece there wasn’t just a who’s who of celebs and stars coming on and waxing lyrical about their on set anecdotes with Brando. It was about getting to a deeper emotional story and the emotional narrative for me is a crucial part. If you can deliver on that in a different way then great, it’s exciting. I’ll always be thinking, whatever film I do, that’s my first approach, really. How can I find an interesting angle into this that’s going to feel… yeah, it’s going to interest me, really. It’s going to make the next few years a bit fun and interesting.

My last question was just having the opportunity to see this in a theater at Sundance was pretty mind-blowing in the sense that when I walked out I sincerely felt like I was in his head for that long. It was this experience that was hard to put into words. I do know it’s getting a theatrical release – which is I great – but it’s also going to be on Showtime sometime this year. I’m sure you’ve viewed this on multiple formats. Have you noticed a different experience?

Yeah, it’s amazing actually how the viewing experience differs. Not just in terms of what screen you’re on but who you’re sitting with. I’m also fascinated by that. If I sat watching it with my mom versus watching it with the Brando family or just with an audience of Canadians versus people in San Francisco – I’ve been to a few festivals – it’s amazing the different feeling you get when you see it through different eyes. Yeah, it ever changes. Bear in mind, I was the editor on the film and spent a lot of time working in low-resolution on a tiny screen or rather on Final Cut in my timeline. It was vastly reduced for the lot of it, but if I’m emotionally connecting with it at that size and it’s working almost as a thumbnail then anything beyond that is just a nice treat. If you get it on a big screen then it’s even more impactful and you have layers of sound and it’s not just stereo through your headphones, then yeah, that just enriches the experience and just makes it more tantalizing and enjoyable. A lot of that work is done at the “thumbnail” stage. It’s always a bonus – I love the conform, when you bring the footage in at high-resolution and everything pops out and all these photos you’ve been working on our now big. You magnify that when you put it on the big screen.

Listen to Me Marlon is now in limited release and will expand throughout the summer before arriving on Showtime in the fall.