I’m not sure I’d think much about diving into the work of Les Blank if only given a plot synopsis. His films, including a plethora now available in a stunningly thorough Criterion set, take on the esoteric sides of America, from bluegrass musicians to the wonders of polka to the taste of Creole cooking. These are the kind of tourist subjects you might expect to see on Travel Channel specials or especially the Food Network. But Blank, who spent much of his life in New Orleans, makes films that don’t just skim along the surface of their cultures, but investigate each little crevasse for characters that enlighten us to their often-secluded worlds. The result is something radical that few documentaries can achieve: authenticity without artificiality.

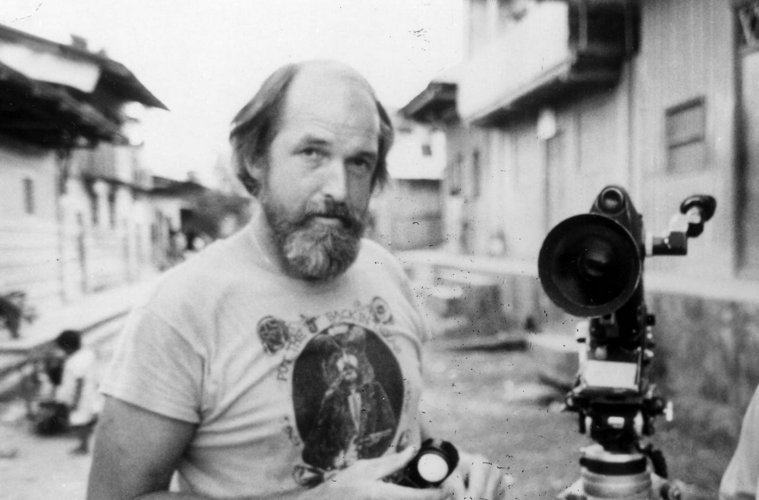

“I try to show that the people in my films are human beings who have just as much right to be on this Earth as anybody else. Maybe more right!” Blank’s films carry a fierce independence, and their relative obscurity over the years have in part to do with the director’s own commitment to self-financing and self-distribution. After completing college at Tulane University, Blank traveled west to study film at the University of Southern California, quickly abandoning work on commercial films that were narration-heavy and moving toward his own interests in the people he bonded with back in New Orleans. Blank never saw himself as a documentarian who was presenting people as much as simply observing alongside the folks. In one of his first films, The Blues Accordin’ to Lightin’ Hopkins (1968), Blank claims, “I started off trying to write a standard script for the Lightnin’ film and it just never worked. Finally, in desperation, I just started throwing scenes together. I found that there was something pleasurable in just cutting pictures like you would notes of music in a music score.” This style of rambling observation, cut to the music of his subjects, became the Blank methodology for the next five decades, up until his death in 2013.

Trying to formally understand Blank presents something of a challenge. His camera doesn’t wander so much as simply follow its subjects, often in handheld but never distractingly so. He isn’t against interviewing subjects (such as Frederick Wiseman) as adamantly maintained, but they appear sparingly. These qualities of amateurism, however, are less apparent when one considers how the wall-to-wall music creates a rhythmic quality, as Blank (alongside partner and collaborator Maureen Gosling) was obsessed with perfecting his films in the editing room, turning what feels like stray observations into a cohesive whole. Even though no effort has a particular narrative throughline (or even story), this editing creates a fast-paced, whirlwind view that feels completely natural. Characters in his music docs certainly emerge — Gerald Gaxiola in The Maestro: King of the Cowboy Artists (1994) and Tommy Jarrell in Sprout Wings and Fly (1983) — but, more often than not, Blank sets up communities with their own ecosystems. The fact that there are so many characters (and the people are often capital-C Characters) makes the lack of central focus feel crucial to each film — they are democratic in the truest sense.

Every community must eat, and food is crucial to so many of the films, if not the main subject (As Andrew Horton notes, Blank often would often come to screenings of his films with a good batch to share). Foodies will find an infinite delight in films like Always for Pleasure (1978) and Garlic Is As Good As Ten Mothers (1980), which show the process of cooking crawfish, gumbos, stir fries, barbecue, and pastas, among many more. It’s not just that the food looks delicious, but that Blank emphasizes the process of creating each dish as ritually different from the kind one could ever buy in a three-star restaurant. One character in the bayou-set Yum! Yum! Yum! (1990) takes pride in his fire-grilled gumbo while a woman in Always for Pleasure delightfully explains what makes her red beans and rice different, debating the merits of adding a single bay leaf. If this all seems like small potatoes, Raymond Durgnant notes, “Blank captures a sense of texture, process, and rhythm…the fruits of a labor which is never a chore or a prelude, but an epiphany, a fetish in itself, part of the chain that links matter with work and finally with community.” The food making is not just an ends to the means — it’s often the center of these cultures.

Blank never focused on big topics, though, given the way culture changed through the decades, his films act as historic time capsules of the forgotten American past. Always for Pleasure captures the true spirit of Mardi Gras — the elaborate costumes, funeral marches, and its context in the history of slave resistance — that resembles nothing like the celebrations that take place on Bourbon Street. (one must appreciate, however, a man who claims New Orleans as the greatest city in the world because of its open-container laws.) Blank dissects a subculture of polka musicians and dancers across the American Northeast and Midwest, who see it as their connection to the old Poland (despite its disappearance from Europe). The community proudly flaunts their eclecticism, seeing it as a way to pass on cultural traditions to the young people — even a high school blonde bombshell explains that, while her friends don’t have weekend plans, she is excited to polka. Despite their very specific time periods, however, there is a timelessness to the way Blank invites us in, making us feel quite at home amongst these communities in a part of America untouched by the numerous crises of the last five decades.

Ethnographic study has long been a part of the documentary tradition, carefully scrutinized to ask necessary questions between documentarian and subject and the right way a film can “show culture.” Today, the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab has led the charge by pushing aesthetics into the avant-garde realm. But perhaps that’s the result of too much intellectualizing. Blank’s films assume nothing about the documentary form because they position nothing. They don’t tackle political issues or try to understand the larger systems at hand. They’re just about showing friendly people celebrating good music, good food, and good dancing. Blank was an absolute radical in a time when documentary cinema needed someone who knew nothing about documentary cinema and everything about culture. Blank’s camera becomes less a machine and simply an arbiter — bringing culture from one end of America to the next.

Les Blank: Always for Pleasure is now available on Criterion.