A recent episode of Amazon’s The Boys showed a superhero shrink to the size of an uncooked grain of rice and walk into the shaft of his lover’s penis. The episode’s creators visualized this orifice as a dark cavern, all wet and leaky, but now we have the real thing—if still wet and leaky, now throbbing with awkward and unmistakable life. This astonishing image, one of many in De Humani Corporis Fabrica, is brought to us courtesy Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, a filmmaking duet who, almost a decade on from their breakout masterpiece Leviathan, continue giving viewers new and vital ways of seeing the world.

Named for a series of landmark studies on human anatomy by 16th-century physician Andreas Vesalius, the setup here is part simple, part miraculous. Paravel and Castaing-Taylor, professors at Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, sat in on and filmed (while also working sound and editing) the various goings-on of hospitals across Paris. There is a morgue; there is a man and his dog walking to work; there is a psychiatric ward and such; but their film is mostly concerned with things happening deeper inside: surgical procedures that they shot live, in-person.

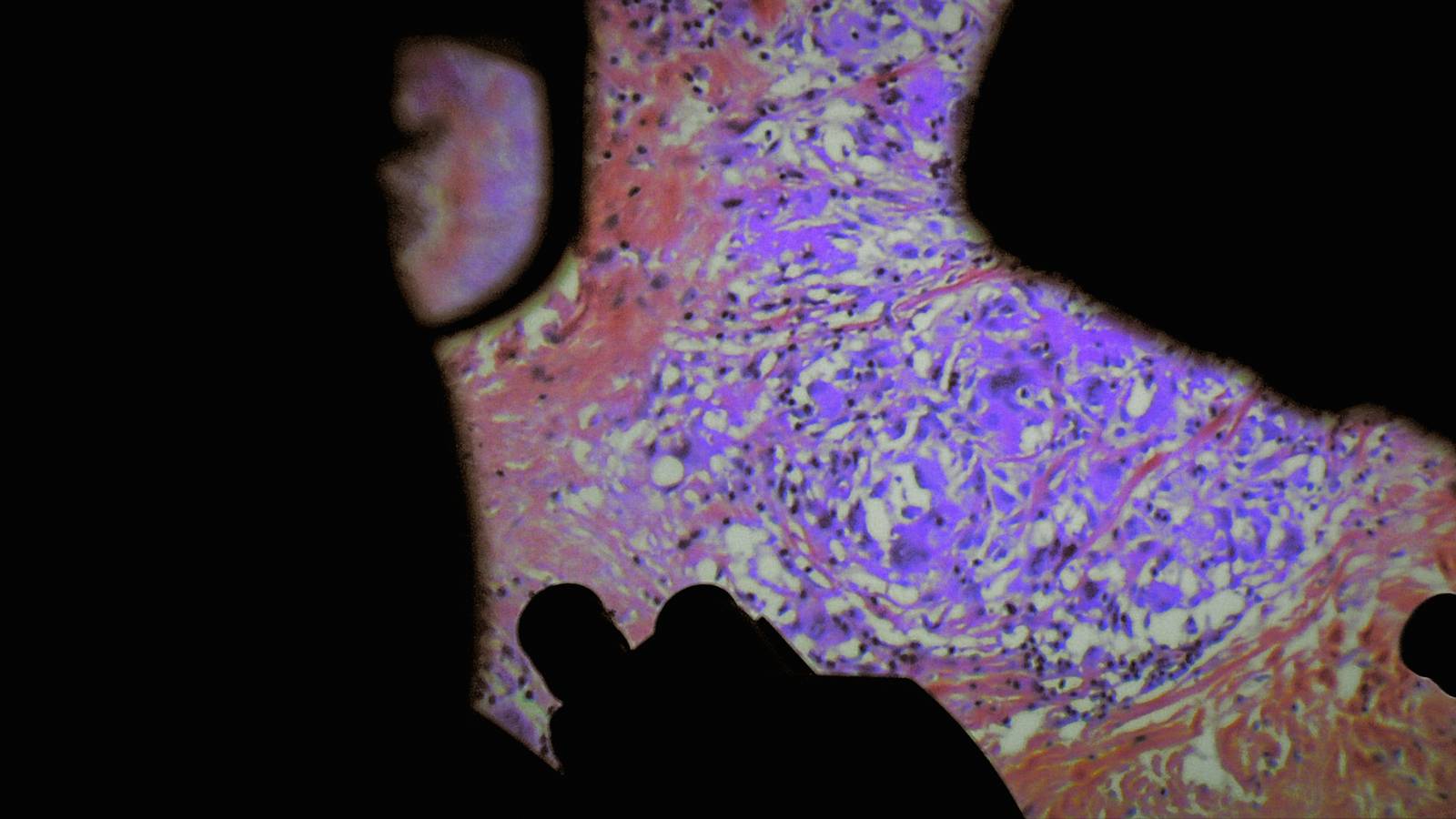

Paravel and Castaing-Taylor immerse us on an Innerspace / Incredible Journey trip through a world of gooey passageways, fragile lungs, and lower intestines—even out an iris. (Plonked into most things mid-procedure, part of the fun is trying to work out where exactly you are.) There is an open back surgery and a grueling C-section. There is the dissection of a biopsied breast that frankly looks like it’s come off a BBQ. It casts an odd spell: you are somehow both removed from the awful traumas surrounding these things while constantly reminded of them. It is not for the fainter of heart.

Or is it? Nobody who watched Leviathan will ever forget that film’s unique alchemy, the strangely humbling effect. They’re after something similarly cosmic here, or at least to remind us of the fragility of our existence in that cosmos, but yet there’s more. Paravel and Castaing-Taylor spare us most slicing and dicing, instead skipping from one carnivalesque grotesque to the next with an often macabre sense of humor. Humani Corporis‘ lasting feeling is undoubtedly profound, and its visuals certainly live up to the billing, but the film does well playing to its own breezy tempo—for every new orifice there is a backing track of pitter-patter from the half-interested doctors and nurses at work, people long desensitized to the gnarlier aspects of their own profession.

In a recent interview with Nicolas Rapold for Filmmaker, Castaing-Taylor said that the original cut was over 10 hours long (“longer than Shoah“), much of which contained detailed prognoses of each procedure. They have thankfully left much of that behind, trimming their film into a 2-hour piece of experimental cinema that, to its benefit, isn’t exactly concerned with grounding one in reality. The only real lags come when we leave the operating table, and they can seem a misjudgment—not least repeated trips to the psychiatric ward, which seem a little on the callous side even as they suggest an effort to shine a light on certain institutional inadequacies.

Paravel and Castaing-Taylor’s work in the ESL has never been short on filmic qualities and Corporis is no different: aesthetically expanding on ideas first hinted at in Caniba and Somniloquies, this is at its visual best when their camera (a tiny probing thing called a “lipstick camera,” originally designed to monitor the engines of racing F1 cars) is left to simply sit and watch, observing a lapsed spinal column that appears like some kind of primordial beached whale, or the galaxy-like swirls of detritus being hacked away in some godforsaken piece of inner human piping, or the implantation of an artificial eye lens—an image so alien it at least equals Glazer’s opening to Under the Skin. The directors’ concerns are academic without ever feeling alienating: in the end, this is nothing if not human, after all.

Anyone looking for a sense of perspective on what we’re made of could do far worse. This film is about fragility—skin and bone, flesh and blood, and excess tissue—but there is an edge of defiance to it: this idea that somehow, even amongst disinterested and overworked surgeons, semi-operational equipment, and endearingly clumsy robotics (I was particularly taken by one cute attempt to put a massive bloody prostate into a zip-lock bag, like packing a school lunch), humanity still manages (sometimes, at least) to find a way to keep this complex piece of machinery ticking on. As Gloria Gaynor sings during the film’s fevered, bracing close, “I will survive, hey hey.”

De Humani Corporis Fabrica screened at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival and will open in the U.S. from Grasshopper Film.