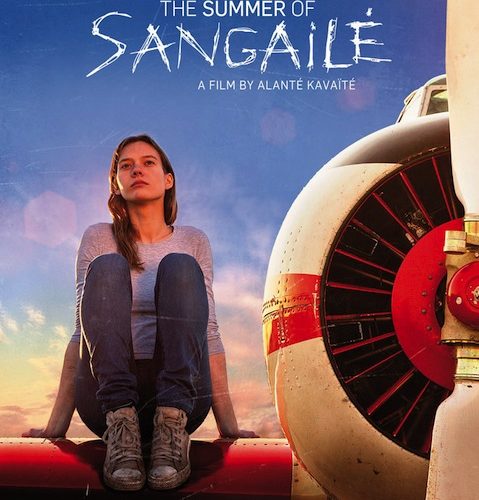

Comparisons between Alanté Kavaïté’s The Summer of Sangaile – the Lithuanian writer-director’s first feature since her 2006 debut Fissures – and Abdellatif Kechiche’s unmerited Palme d’Or winner Blue Is the Warmest Color are likely inevitable. Despite distinct thematic and narrative similarities between the films, however, in terms of sensibility and aesthetic approach, Kavaïté’s portrait of a teenage girl’s first same-sex romantic experience couldn’t be more different from Kechiche’s. A crucial distinguishing factor is the mixture of humility and affection manifest in Kavaïté’s direction. Free of condescension and uninterested in enlightening the viewer, The Summer of Sangaile is an intimately involving celebration of the fiery passions that accompany pivotal periods of adolescence.

The central relationship is nested within the coming-of-age trajectory of the film’s titular protagonist, 17-year-old Sangaile (Julija Steponaitytė). While vacationing with her parents in the countryside, she meets Auste (Aistė Diržiūtė), a local girl who introduces Sangaile to her group of friends. The two soon become lovers, and the blossoming of their romance occurs in parallel to Sangaile’s overcoming the crippling vertigo that is preventing her from pursuing her dream of becoming a pilot. Although neither the plot nor aviation metaphor are particularly original, this film never pretends otherwise. On the contrary, its script is purposely kept stripped-down and familiar in order to give primacy to the story’s emotional dimension. It’s actually in the few attempts at embroidering its narrative that the film loses some strength. Plot points such as Sangaile’s sleeping with a boy prior to getting together with Auste or her habit of cutting herself with dividers feel superfluous, constituting rare instances in which Kavaïté enters clichéd territory.

Her innovation instead lies in methods of conveying Sangaile’s frame of mind through a constant fluctuation between naturalism and artificiality, with the balance shifting towards the latter in conjunction with the escalation of the emotions on screen. This is sometimes taken to near-fantastical extremes, and climactic scenes — e.g. the girls’ first coupling, which takes place in a field at dusk as both wear ballerina costumes decorated with Christmas lights — reflect the ecstasy of the moment by blurring distinctions between reality and dream.

Stunning lensing by cinematographer Dominique Colin plays an integral role in fulfilling the film’s impressionistic impact. Shot over the course of a spectacular summer in an idyllic rural setting, The Summer of Sangaile is composed of a continuous stream of gorgeous, effortlessly evocative images. In addition to extended sequences of airplane acrobatics, it also features a highly versatile use of drone shots. The bulk of this film is composed of static frames to illustrate Sangaile’s inhibition, camera movement largely being reserved for representing her flights of fancy. Later, as Auste impels her to overcome her fear of heights, drones are used to great effect by framing Sangaile in overhead shots from dizzying heights, transferring her vertigo onto the viewer.

Further buoyed by Steponaitytė and Diržiūtė’s excellent performances, as well as a breezy pop soundtrack composed by JP Dunckel (one half of the French electronic duo Air), The Summer of Sangaile’s compact 88 minutes are as transporting and pleasurable as an extended reverie. When Sangaile finally climbs into a plane’s cockpit at film’s end and disappears into the sky, it’s a privilege to share in the elation of her triumph.

The Summer of Sangaile screened at Karlovy Vary International Film Festival and opens on November 20th.