Early into Mediterranea, Jonas Carpignano‘s debut feature, a pair of African immigrants who’ve recently arrived in Italy are standing on the platform of a rural train station. In the background, the sign indicating location reads “Rosarno.” For Italian viewers, this image will immediately trigger an association with the two-day race riots that erupted in the small Calabrian town of Rosarno in 2010, events which received massive media coverage and caused a scandal by exposing the inhuman treatment of the region’s immigrant workers. Though the riots were reported internationally as well, they’re unlikely to have remained as firmly imprinted in popular consciousness abroad as they domestically, where they represented the most extreme manifestation of a national and continental crisis that has only been worsening for decades. Neglecting this disparity in awareness is Mediterranea’s critical weakness. Though realized with great empathy and tact, the film fails to convey the catastrophic extent of the situation it addresses by keeping its narrative too tightly focused.

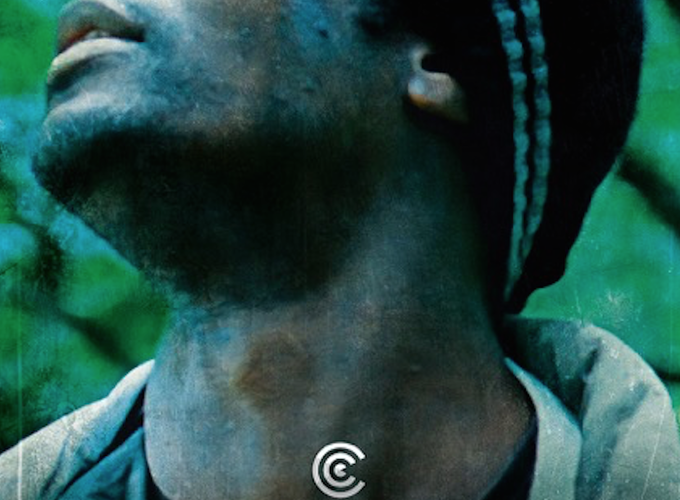

Despite this unintended result, such a micro-approach is deliberate. At one point in the film, an older Italian woman complains that the news is always telling “the same story.” By giving a face to the plight of African immigrants crossing the Mediterranean to seek work in Europe, a fixture in the news, Mediterranea intends to redress the passivity engendered by repetition. The two men at the train station are best friends Ayiva (Koudous Seihon) and Abas (Alassane Sy). After making it to Italy in a journey that involved crossing a desert on foot and surviving a shipwreck, they eventually manage to receive a permit to stay in the country for three months and head to Rosarno in the hopes of acquiring an employment contract and becoming eligible for a permanent work permit. While Abas quickly turns despondent, disgusted by the conditions of the immigrants’ encampment and the pitiful pay they receive for breaking their backs picking oranges all day, Ayiva – who emerges as the main protagonist — remains optimistic, determined to receive the coveted contract by proving himself through hard work.

In addition to directing, Carpignano also wrote the script, and he deserves praise for eschewing sentimentalist clichés so frequently used in similar films. Ayiva is neither portrayed as a saint nor are the small crimes he commits (out of necessity) overly labored upon. Rather, he is a likeable and fully believable person for whom it’s impossible not to empathize. Equal credit goes to Seihon for impersonating him so convincingly. The Burkinan actor actually experienced a trajectory similar to Ayiva, making the perilous journey across northern Africa and the Mediterranean — though he was more fortunate upon arriving in Italy — and his personal experience imbues this performance with a high degree of naturalism.

Following Ayiva through day-to-day struggles, the film is fully engaging as it charts his gradual, steady upwards progress, and the knowledge of impending riots only renders his efforts all the more tragic. However, in its resolve not to exploit the subject matter, Mediterranea ends up going too far in the opposite direction. For instance, the immigrants’ working and living conditions, though dismal, are not rendered anywhere near as awful as the reality, which at the time was widely reported as a small step above slavery (the rioters’ protest chant was “We are not animals!”). The same is true for the notoriously vicious racism that immigrants have to endure in Italy, especially in regions such as Calabria. Apart from a few isolated instances, the characters are not shown as being particularly discriminated against because of their race, and when the locals turn violent against them in the riots, it comes across primarily as a direct retaliation for the damage inflicted on cars and properties.

Most crucially insufficient is the attention given to the mafia, whose role is treated so cursorily that it’s certain to escape all those unaware of the underlying politics. The mafia controls most of the illegal labor in Southern Italy, and, by being implicated in every aspect of governance, is in large part responsible for the perpetuation of what has escalated into a veritable humanitarian disaster. Here, the mafia is never explicitly mentioned, and only depicted in a few scenes where shady characters appear and cast a threatening presence, but their actual role remains unspecified. When Ayiva finally gets the courage to ask his employer whether he’d give him a work contract, the latter simply replies that he can’t. Although he then goes on to talk about how Italian immigrants in the United States helped each other and formed “families,” it’s a stretch to expect viewers to construe that it’s because of the mafia that Ayiva and the others have no hope of ever legitimizing their employment.

Carpignano is a skilled filmmaker and, strictly regarded as a viewing experience, Mediterranea is extremely well-crafted and thoroughly moving. Regrettably, the narrative’s inadequate contextualization ends up diluting the film’s effectiveness as a call to action — which it not only aspires to, but also deserves to be.

Mediterranea screened at Karlovy Vary International Film Festival and opens on November 20th.