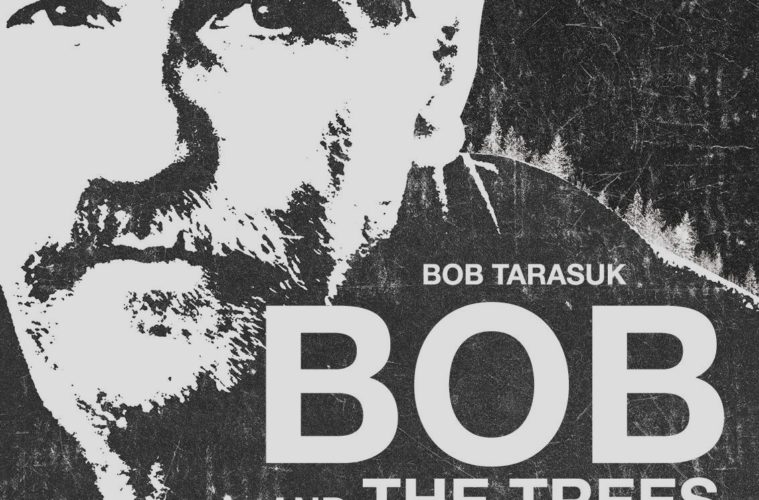

Following its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Diego Ongaro’s Bob and the Trees was featured in the main competition at Karlovy Vary and walked away with the Crystal Globe, the festival’s top honor. Ongaro’s debut feature, expanded from his 2010 short of the same name, depicts a winter in the life of Bob Tarasuk (playing a lightly fictionalized version of himself), a logger and livestock farmer from the Berkshires. Although the film benefits from Tarasuk’s strong central presence and a palpable sense of directorial empathy, Ongaro isn’t entirely successful in straddling the threshold between documentary and fiction. The result is an awkward hybrid that is both too scripted to convince as a genuine slice of life and too muted to keep the viewer involved for its full running time.

Ongaro achieves documentary realism through familiar tactics such as a handheld tag-along aesthetic, a cast primarily made up of non-professionals and a loose, faux-incidental narrative structure. If it weren’t for the editing, which betrays the film’s verité-style naturalism from the start, Bob and the Trees could initially pass as a documentary, following Bob as he tends to his farm animals and gets to work on a new logging commission with his son Matt (Matt Gallagher, Tarasuk’s actual son-in-law). However, the combination of obvious scripting and stilted secondary performances eventually dispels the film’s authenticity altogether. Too many of the dialogues are transparently devoted to relaying information to the viewer, so that when characters discuss the specifics of logging, the rationale behind working in the harsh winter, or the increasing untenability of the profession, it often feels like talking heads commentary forced into a fictional framework.

Given that the plot developments themselves are purposely mundane, the film struggles to engage the viewer once the storyline’s fictitiousness has become apparent. Thus, when a large portion of the trees that Bob and Matt are logging turn out to be infested with ants and therefore worthless, the threat to their entire livelihood hardly registers as a tragedy even though it’s meant to represent the real, potentially fatal risks they face every winter. In the same way, when Bob’s escalating anxiety gives way to paranoia and he lashes out at those around him, accusing them of sabotage, it all comes across as overdetermined.

Surprisingly, the cinematography takes very little advantage of the location to supplement the narrative. The drab color palette and unimaginative camerawork neither evokes the nature’s majestic beauty, nor the arduousness of working outdoors in the Massachusetts winter, combatting the waist-high snow and sub-zero temperatures – even the sight of gigantic trees toppling over fails to elicit the slightest excitement. The attempts at injecting pathos into Bob’s predicament amount to little more than stylized close-ups of ants, accompanied by an overdramatic ambient score, both of which feel incongruous within the film’s otherwise unembellished style.

Thankfully, Bob is a spirited and naturally charismatic personality and it’s easy to see why Ongaro – a Frenchman who recently moved to Massachusetts – would have been motivated to structure a film around him. Nevertheless, while Bob and the Trees works well on the level of a personal portrait, it would have required much more compelling contextualization in order to legitimate a feature-length treatment.

Bob and the Trees screened at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival and is seeking U.S. distribution.