Jerry Schatzberg is among the great American filmmakers who changed the landscape in the 1970s, but his name is one that has taken some time to get the recognition it deserves. While he may not have landed with the same initial impact as a Francis Ford Coppola or Martin Scorsese, the years have been kind to films like The Panic in Needle Park and Scarecrow, invigorating a passion that ranks them as some of the decade’s very best.

A renowned photographer with work in magazines such as Vogue and Esquire, Schatzberg is also responsible for the iconic cover of Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. This was all done before he made his feature debut with 1970’s Puzzle of a Downfall Child, starring then-fiancée Faye Dunaway. That would begin a career working with some of the best actors the world has ever seen, from Al Pacino and Gene Hackman to Meryl Streep and Morgan Freeman, who earned his first Oscar nomination for Schatzberg’s 1987 film Street Smart.

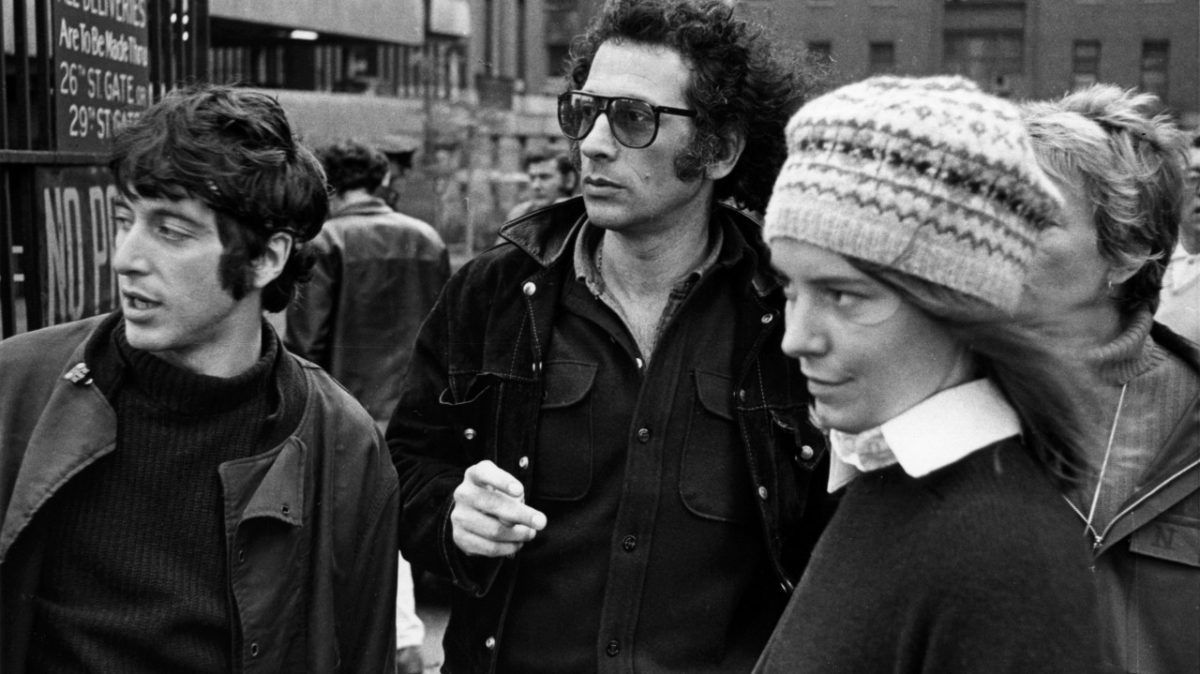

With this year marking the 50th anniversary of The Panic in Needle Park, his drug-addiction drama starring Al Pacino and Kitty Winn, the 94-year-old Schatzberg carved out some time to speak with us about his beginnings in the film industry, the enduring legacy of his pictures, and to share some incredible stories from back in the day.

The Film Stage: At the end of the 1960s you were a very established photographer, then made your first shift into directing with the film Puzzle of a Downfall Child. What inspired that decision to take on this new artform?

Jerry Schatzberg: I had become very friendly with a great model [Anne St. Marie] who had offered to do some pictures for me, as I was always doing test shots. I had been thinking of doing a film for a while, but didn’t know what it was going to be. Speaking with this model, she told me about how she had this breakdown, and I thought this was interesting material, so I decided to tape her. In that same time period, I had gotten to know Faye Dunaway after I was sent down to Florida to do some photographs with her for her first film, when she was an up-and-coming actress. So, a few years later, after Faye had done Bonnie and Clyde, we had lunch and she asked me what I was working on. I told her that I would love to do a film, which piqued her interest, so I got her to listen to the tape.

Was she interested right away?

Now, this tape was two and a half hours long. Faye listened to the whole thing, and she fell in love with the character. From that point on, she was part of the project. We went through several writers after that. I had a French writer [Jacques Sigurd] at first, who turned in a script that wasn’t bad, but he was a pain in the ass. When he finished the script I said there were some changes I’d like to make, and he couldn’t believe that I would have anything like that to say, especially as a first-time director. So, I got rid of that problem. After some other writers fell through, we had a script that I loved from Carole Eastman, who was a wonderful writer.

How did Carole come on board?

This kind of thing never happened to me, but I was in an elevator in California, and when the elevator cleared out I heard someone shout from behind me, “Hey, are you Jerry Schatzberg?” It was a producer, and he told me that he had this great script that they weren’t going to use because the director didn’t like it. I got a look at the script and found it so funny, so sharp, and so I got the number of the writer, who was Carole. We got on the phone, and I told her I’m working on this project with Faye Dunaway in the lead, and we were looking for a writer to do the script. I was renting a house out in California at the time, and I asked Carole if she’d come over so I could talk to her about the film. She came over, and immediately was talking about how she has a friend of hers in the car with a very bad toothache, who she has to take to the dentist. She was already preparing her escape, you know?

What did you do to convince her the project was a good idea?

I asked her if she would listen to the tape that I had made, just hear the story and see if she was interested. When I told her that it was two and a half hours long, she tried to run out of there quickly, but I begged her to listen to ten minutes of it, so she did. She started listening, and soon enough she had listened to all two and a half hours. She was so affected by it, and wrote a brilliant script for it. We went through a bunch of different producers. Ismail Merchant was interested, but was too busy doing a film with James Ivory to work with us. Bob Evans wanted to do it, but he thought that we were making the next Blow-Up until he saw the script, which he absolutely hated because it was nothing like Blow-Up.

We eventually got Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward to read Carole’s script, and they loved it. Joanne said she had a roommate once who went through the same experience. We were all set for this to be my producing team. Then one day, I went up to Connecticut to show the new draft of the script to them, and when we were getting ready to talk about it, Joanne came running out of the house crying. It seems they were friends with the hairdresser that was murdered along with Sharon Tate. Sharon was a very good friend of mine, because I was quite good friends with Roman [Polanski]. So, this news blew up that meeting, and after that we couldn’t really work together on the film anymore. They were always great though, always available to call for questions or advice. And we just moved on with the project from there.

That’s quite the rocky way to get your start in the film industry. Was it easier going to get started on The Panic in Needle Park, your second film?

Well, I actually thought that I was only ever going to do one film. With Puzzle of a Downfall Child, the lab had a problem with their machinery where a screw came loose, and it scratched the last six minutes of the film’s negative. I was extremely upset about that because for a long time I had to live with those six minutes being this poor quality until they developed better printing methods with digital and I was able to fix them. So, it took me a bit of convincing to even want to make a second film in the first place.

I read that you also turned down the film initially because you didn’t want to do a film related to drugs. What was your resistance to that subject matter?

My business manager told me they had a great script, so I asked him what it was, and he said that it was called The Panic in Needle Park. It just didn’t feel right to me. I had a lot of friends that had been involved in drugs, who had so many of their own sad stories. I didn’t know if I would be interested in that, particularly coming off Puzzle.

What eventually turned you around on the project?

Well, five or so years before this I had gone to the theater with my manager, Marty, because he wanted to try and sign Al Pacino to a contract. Watching Al on the stage, he was just fantastic. I said to Marty, “Boy, if I was to make another film, that’s the guy I’d like to work with.” So, Marty tells me that Al is interested in doing Panic in Needle Park. I went back home that night and read the script again, imagining Al in this part, and it completely changed everything for me. I wanted so badly to work with him, and that’s what really got the ball rolling.

Hollywood films about drug use can often feel inauthentic in one way or another, the type of depiction you’d see from people with no understanding of the world they’re showing. Panic in Needle Park is quite the opposite. How did you work to bring that sense of realism to the world you’re portraying in the film?

If you look at my photographs, I think it’s a very similar thing. They’re never just the model standing there, one hand in the air in some odd pose. They’re much more honest. That’s what I was always looking for. Fortunately for me, I had two actors who didn’t have much to do. We spent a month and a half researching and talking and being together before we ever got to do proper rehearsals for the film, which was a huge advantage. We all got to know each other quite well. Al put me onto a lot of his actor friends as well, some of whom were junkies, and I certainly think having that experience there helped the project.

How did you feel your film compared to those other drug-related films at the time?

I looked at the last American film about drugs, which at the time was Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm. That film didn’t really appeal to me that much, but that’s the kind of thing that was around. Funnily enough, the word had been getting around about our film, and Preminger asked either my agent or his agent or somebody if he could see the film. We said sure, and so he came to the screening room. My editor and photographer and I were sitting in the back. He didn’t come and say hello. He walked in, took a seat to watch the film, and then he walked out. Didn’t say a thing. What a prick.

He wasn’t a fan then, I suppose?

I guess not. That’s just part of the funny little things that happened along the way.

One of the things that stands out about your film is the depiction of the drug use itself. You don’t shy away from it, often showing extreme closeups of needles being injected. Why did you want the audience to get up close and personal in that way?

I’m very logical about certain things, and I figured how could you show a film about drug addiction if you don’t show that? That’s part of the horror of drugs. An interesting thing is when I met Kitty Winn, a big part of why I knew she was perfect for the role was because she was someone very innocent, someone who didn’t know anything about this drug world. Before we made the film I asked her how she felt about the nudity in it, because these characters lived together so the actress was going to need to be nude in it sometimes. I wanted to show this life as it really is, so I needed to show the drugs, to show the nudity, to show people really living together. I needed to make sure she was going to be prepared for that, because I didn’t want her doing anything she was uncomfortable with.

So, Kitty thought about it, and got back to me and told me that it would be fine. However, once we started shooting, every time we would go to shoot scenes with nudity, she would find some excuse to need to put it off longer and longer. I was accepting of it until the very end, when I had to just say, “Kitty, we have no more time. We’ve got to shoot this.” I told her we’d make it as comfortable for her as possible, and we did. She got it done. Then, after we finished filming everything, she told me that the thing she was worried about was her grandmother seeing it. But, she got it done, and she was tremendous, and even won a prize at Cannes for her performance.

While the film did win a prize at Cannes, other European boards were a lot more resistant to it. The UK even banned it for several years. Why do you think censors over there were so afraid of the film?

The films in America at that time that were about drugs were really Hollywood versions of drugs. So, they didn’t pay any attention to that sort of thing. I guess this was too strong for them, or too honest for them, so some board in England said that we just couldn’t play it there. Here we are now though, 50 years later, and it’s still playing.

You reunited with Pacino a few years later on Scarecrow, which is an absolute masterpiece of American cinema.

Oh, please go on. I love this.

Just being honest! I read that Pacino and Gene Hackman didn’t get along very well on the set of the film. Where did that conflict come from for the two of them?

Basically I think it came from them having two very different acting styles. Al will get into a character and never get out of it until after the whole film is finished. He doesn’t get a call to come to set and quickly slide into the role. Hackman is the opposite, where he puts on the costume and is absolutely great, but he takes off that costume and he’s back to Hackman. It’s a different pace for each of them. They were civil to each other, they spoke to each other, but they definitely weren’t buddies. Hackman is not an easy guy. He would get mad at someone, anyone on crew, and complain to me, and I’d say, “Gene, you don’t get along with anybody!”, and he’d say, “I get along with you!” He was great to work with, but maybe not the easiest for everyone.

Rumor has it you’ve written a sequel for Scarecrow. Is that true?

I’ve written one, yeah. Al won’t even read it. With Hackman retiring, Al won’t even take a look at it. Which is funny, because when Al saw Scarecrow his manager told him that it wasn’t even his film because Hackman was so strong as a character. So, his manager interpreted it that way, and came to me saying that, and I was furious. Some people left the screening room talking about how Al is so amazing in it, and some came out saying Hackman was the star of it. It was sort of 50/50. As long as some people thought each of them were great, I felt good about it.

Could you tell us anything about what that sequel might have looked like if you were able to get it made?

Al’s character changes completely in it, because he was so young in the first one. I had plans for him to go back to school and everything. Then they would open this successful car wash, which Hackman would think was his, as he does in the first film, but it was really the Pacino character who would be running it and making it successful because he had gotten an education to become a different person. It would have been quite different. I thought of using different actors at times, but it really didn’t feel worth it. I worked on it for quite a while, though.

Those first three films of yours were made in the early 1970s, during what’s become known as the New Hollywood movement, and have grown in stature over the decades. Towards the end of that decade there was a dramatic shift where studios became more stringent, not giving the same latitude to filmmakers that they were before. How did that impact the work you wanted to be making?

I hate some of the films that I did, and I push them aside. There’s one that I denounce altogether. I won’t tell you which one. However, for the amount of films that I did, which was not that many, I’m quite happy with them. I think those first three were brilliant. Some of the others were really good. The studios were always trying to mess around, and it only got worse over time.

Was there anything particularly egregious with them on Panic?

Well, casting was a problem. They actually wanted me to use Mia Farrow in the Kitty role. I said, “What are you thinking?” She’s a wonderful actress, but they wanted me to make her a junkie? She was too well-known, and just wouldn’t be convincing at all. So, we got our way there with Kitty. Pacino was another story.

Tell me more.

They didn’t want Pacino. They thought he was too old. I didn’t appreciate the studios making their mind up like that, when it was already understood that Pacino was going to be Bobby. So, what we ended up doing was having a full casting, with the full intention of going back to them and saying that Pacino was still the best we got. It’s funny, the last person who came in for it was actually Robert De Niro. He was pretty good, but I had my heart set on Al. I ran into De Niro once on Third Avenue at that time. We didn’t really know each other, but he stopped me and said, “Hey man, I really want to do that part.”

Oh no, what did you say?

I was like a deer in the headlights. I didn’t know what to say, so I just told him the truth. I said, “I’ve wanted to do it with Al for so long, and Al is really on my mind.”

How did he take that?

He walked away, and through the years we’d see each other and sort of nod to each other, but never speak. Then, we had a tribute for Morgan Freeman one year, and at the end of the tribute we were all supposed to go out on stage and take pictures. I was standing on stage already, and De Niro was the last one to come out. He walked past me, and then suddenly stopped and came back to me, and he said, “Hi, Jerry!” It was the first time in 40 years we had spoken to each other. He got over it finally.

The Panic in Needle Park is streaming now on the Criterion Channel, and will have a 50th anniversary screening at the Film Forum on Monday, October 11, 2021.