Emerging from his politically radical period of low-budget, didactic political commentaries with revolutionary overtones, produced primarily on 16mm or tape for television broadcast, prolific French avant-garde iconoclast Jean-Luc Godard unexpectedly returned to commercial filmmaking with Every Man for Himself, finding reinvention in the age of video — a new formal frontier for the now-middle-aged provocateur. Godard’s star-studded return to more conventional cinemas, featuring Isabelle Huppert, Nathalie Baye, and Jacques Dutronc as Paul Godard (of course), a loathsome filmmaker humiliated by having been reduced to working for a TV studio, though shy of being considered a phenomenon in France or elsewhere, was well-publicized worldwide. Uncharacteristically, the aging filmmaker promoted the film extensively, pensively referring to it as his “second first film,” a somewhat deadpan admission that, to begin again, he had to shed the baggage of his underground period. Through this mainstream amelioration began a self-reflective period of filmmaking, reverse-engineering his formal fascinations — disruptive non-linear editing, elliptical storytelling with provocative camera angles, and a cast of characters made up of deterministic, allusion-spouting ciphers — and probing them with the properties afforded by advances in video technology, an extension of Godard’s predominantly on-the-fly approach to filmmaking, in the past having utilized handheld cameras in their infancy.

Shooting and editing on video allowed for unprecedented manipulation and replay access to the filmic space from outside the space in question, a dissonance that Godard gravitates toward in Every Man by emulating the effects on 35mm and with deliberate direction. Scenarios are infused with an uneasy self-awareness, akin to the improvisational elements present in his earlier films but subsequently protracted and rewound and sped-up and slowed down with layered dissolves or perhaps voiceover — all to maximize an internalized awareness of the artifice of the frame. While Every Man was shot in 1.66:1, it found new life on TV in 1.33:1, the native aspect ratio for broadcast, which Godard would continue to work with throughout the decade. For subsequent films, analog techniques from the past are resurrected via video and techniques inspired by it, and multiple-exposures and altered frame rates are now experimental editing artifacts layered on-top of recyclable, highly malleable tape, in contrast to the tangible fragility of film stock.

The paradox of starting over again with years of knowledge and experience is likely not lost on Godard: all of his ‘80s films deal with the filmmaker’s personal struggle to reconcile the differences of working in the demanding world of commercial television in contrast to his native arthouse cinema. Approached by television executives to contribute to a curated series of films, Série noire, alongside other notable directors, Godard seized the opportunity to make a film about his own incongruous and troubled relationship with the two mediums. Commissioned by French TV channel TF1 in 1986, Grandeur and Decadence: Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company is another irreverent installment in Godard’s bewitchingly self-reflexive midlife crisis, excavating the proclivities of a narcissistic but brilliant artist who’s past his prime and seeking to return to the past.

Pitched as an adaptation of James Hadley Chase’s pulp novel The Soft Centre, it ostensibly chronicles the “rise and fall of a small film company,” a subtitle that only becomes apparent nearly 20 minutes in, as frequent cutaways to black slides with white text separately bearing the film’s title and the subtitle’s subject and predicate before they’re combined into a cohesive whole. These textual impositions reappear throughout as chapter headers-of-sorts emphatically underline a particular concept: “The Omnipotence of Television,” “An Old Story,” and even a lengthy musical interlude about “The Mercedes” set to Janis Joplin’s “Mercedes Benz.”

A filmmaker with a dogged temper, Gaspard Bazin (Jean-Pierre Léaud, so absurdly erratic that at one point he changes sweaters mid-conversation) directs for a French TV studio, producing increasingly bizarre adaptations of banal crime novels and spectacularly losing his mind in the process, holding maddeningly tedious casting calls where those who audition individually recite subjects and predicates from Grandeur and Decadence’s own source material; each variation likened to that of a “wave” in a story’s “ocean.” Bazin used to make “cinema,” a term so offhandedly invoked in the work of Godard’s heyday, here treated as a taboo or sore reminder of times past, only spoken of by its castoffs in private — in dimly lit night cafes and second-class apartments. Among these exiles are Jean Almereyda (played by director Jean-Pierre Mocky), something of a confidant and an intellectual rival to Bazin, nevertheless bonded through their mutual atrophy, and his wife, Eurydice (Marie Valera), a failed screen actress trying to break into TV, seeing working with Bazin as her best chance before things start to fall apart.

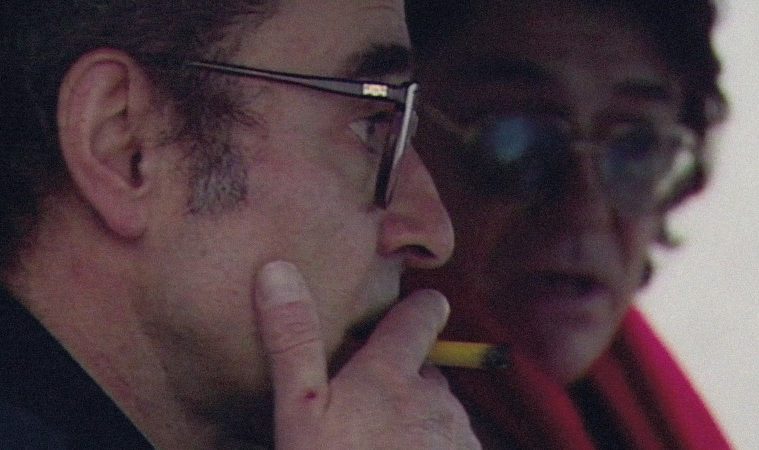

As is par for the course with Godard, the main narrative thread is often lost, dropped, and then recovered as the film flits through ideas ranging from the influence of the televisual medium on the future of cinema to the effects of cultural reproduction brought on by mass production of videos, CDs, and reprinted art and literature in the form of countless reissues. Gaspard Bazin — whose namesake, Andre Bazin, wrote extensively on the conceptual groundwork of the reproductive nature of cinema — at one point is in one of his irritable moods and tries to write but can only seem to do so in peace as long as the Bob Dylan song he’s playing on cassette loops through a particular section, prompting him to have to repeatedly run to the back of the room and manually reset the tape. Another time, he finally lets down his guard with his stalwart partner and passionately embraces her before launching into an egomaniacal test, asking her to count the characters present in paintings such as Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, loudly disagreeing with her answers as the film shows only portions of the pieces and positions them out of order. Adding to the temporal disconnect, Godard himself even shows up at one point, only to discuss Roman Polanski’s inflated budget for a TV movie with Almereyda and impart cryptic, portentous koans such as “Everything goes backwards: fashion, politics, and therefore cinema.” Drenched with deadpan humor, these are welcome diversions in a work that, though utilizing non-linear editing structures, follows a generally linear plot progression.

Bazin and Almereyda are mixed up in a real-world crime so absurdly opaque that it resembles fiction, so silly it might as well have been written on a napkin — a group of rogues involved in pseudo-espionage, nabbing important “documents,” finding missing “German marks,” and having clandestine meetings at train stations. Eventually, Almereyda, clad in drag, is revealed to have been in on the robbery all along, or so it seems, and is trying to double-cross his mainly unseen compatriots. They catch on and ominously declare that the proverbial “train station” is waiting for Almereyda as they close in on him. Cut to the police finding all of their bodies in a Mercedes Benz parked outside of Almereyda’s office. Bazin is questioned, but the authorities conclude that he doesn’t fit the type. Bazin is relieved and offended. He visits an electronics store and is able to see and listen to recordings of Almereyda over the equipment, a disconnect that hits hard as Léaud anchors the edgy character in another moment of vulnerability and wistful remorse. Bazin is reduced to participating in the same inane casting calls he used to run, except some of his crew are working for the office’s new occupants, humiliating him even further when his answer to the free-form audition is from Almereyda. Nonetheless, Bazin is able to return home to his partner and child. As he embraces his son and puts him on his shoulders, the frame freezes, becoming a moment eternally paused in time, and then the film ends.

From a glance, Grandeur and Decadence is interested in ideas similar to those in Godard’s other work from the ‘80s — such as Passion, which explored the reproduction of art through striking replications of famous tableaux vivant — but its quality should not be undermined by its relative obscurity. Take Bazin’s casting calls as an example: treating them like an assembly line, amateur actors delivering lines from deliberately assigned cue cards, effectively measuring the separation between reality and fiction indirectly, through sheer repetition. The film is not one of tedium save for when it’s done humorously so, such as with the flagrant references to Bazin and even Rocky IV. What results is a fascinating satire of the toxic masculinity and egos of the TV industry, and a self-deprecating reflection on Godard’s own sense of personal fracture. Grandeur and Decadence is a key entry in Godard’s transition back to commercial filmmaking, helping establish a new period of existential, autobiographical filmmaking influenced by the ontological questions brought on by advancements in filmmaking technology.

Grandeur and Decadence screened at the 2017 New York Film Festival.