Crowdfunded Cinema is a new column at The Film Stage, and one that we’re very excited about. This column will focus on filmmakers seeking funding for projects via crowdfunding platforms, offering new ways for independent artists and audiences to connect. With each article, we will focus on a single project that we find particularly interesting and inspiring.

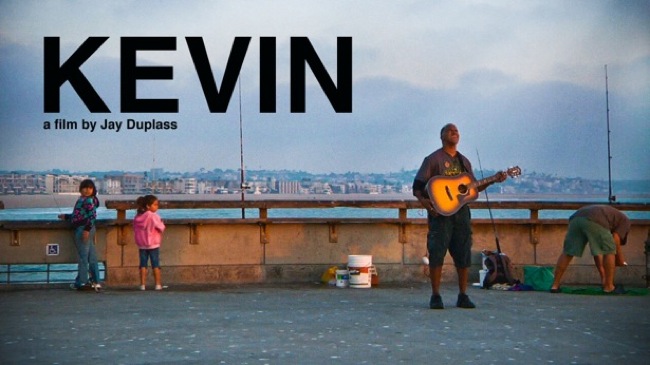

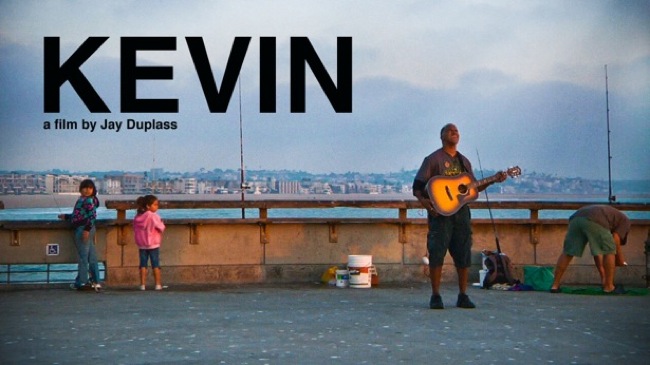

Kevin is the documentary debut director Jay Duplass (The Puffy Chair, Baghead). The film focuses on Kevin Gant, and Austin musician who was very inspirational to Duplass in the early 90s, but who then vanished without a trace. Now, fifteen years later, Duplass tracks down Gant, to both reconnect with him as well as what caused his disappearance. The result is a very heartwarming story that introduces an undiscovered musical voice into the world. The film premiered at SXSW, and is now looking to raise funds via Kickstarter to launch a wider festival tour, continuing to share Kevin’s story and music with audiences.

We caught up with Jay Duplass recently to discuss the project, and were left feeling very inspired and excited by it. We encourage you to read our interview below, but please also consider visiting the project’s fundraising page, and donating.

TFS: Tell us briefly about how you came to know Kevin, and how this project came about.

Duplass: When I was in Austin, TX in the early 90s going to film school, I had grown-up in New Orleans, and it was kind of an odd time in college, kind of uninspired, honestly. My brother came to visit me one weekend, and we went out to see some music and we saw this guy perform, and I had never seen anything like it before. He’s playing in a folk venue and does play guitar, but he has this crazy flamenco style that sounds like a full orchestra, but it’s just coming from his fingers; you can tell that it’s not trained, but rather something he picked up. His singing is soulful, with almost New Age lyrics but not. It was very cosmic, and it wasn’t constructed, it was very obvious that this is how this guy thinks. And, he looked kind of like O.J. Simpson, and built like a weight-lifter, so he was like the most unique thing I had ever seen, but beyond that, without a doubt, he was the most inspired person I had ever seen, and still is. He ignited me in a lot of ways, and kind of gave me the guts to be more individualistic in what I wanted to create and what I wanted to do, and truly to be myself.

I went to as many shows as I could, and then in 1995, he disappeared. He just stopped playing shows, and no one really knew where he was or what happened to him, and everyone was just wondering, and he never reemerged. I would scour the internet and newspapers for close to fifteen years, but I never found him, never saw any evidence of him. Then, basically, a couple years ago when I was doing movies with my brother, I needed a re-ignition, needing to get re-inspired. So, I went looking for him, I went to Austin. I went to go find him.

Through some internet research, I could tell that he was around, but it wasn’t playing, I just saw evidence of a Kevin Gant living on the east side of town. I ended up finding him, and I got to ask him all the questions I always wanted to ask him about; “Where does that stuff come from?” and “What happened to you?” He had a really dark story about trying to come to LA to make it, and was basically beaten to within inches of his life, in what he later figured out was a gang-related initiation attempt. He had just been through a ton, and both of his parents had just died and he’s a single child, and he basically just shut his life down.

I came home and was really depressed. I was like “I need to do something, or something needs to happen, because this guy is kind of on the way out.” He told me when I was interviewing him that the reason for the way that he played was he was obsessed with flamenco guitar when he was a kid. He had this tape, and he would just listen to this, and sleep with it, and listen to it all day. He just felt this deep deep connection to gypsy music and this place that he had no tangible connection to whatsoever. When he told me that, I had this flash in my mind like, “I think we’re going to Spain,” but I was like “How’s that going to happen? That’s strange, and how am I going to explain to my wife that I going to go to Spain with some weird guy that she doesn’t know?”

So, I got home to LA, and was just kind of confused and wondering what to do, and the next week I got invited to a Granada international film festival, which is the birthplace of flamenco guitar. This is how Kevin’s life works, cosmic connections in that way. I was like, “I’m getting sucked into Kevin’s vortex again.” So, I called the festival and told them what his situation was, and they agreed to fly him to Spain with me. We went there, and it kind of re-ignited his dream as well as mine.

Now, we’re taking the film out to film festivals, and Kevin’s an old school performer, [so] we’ve been having Kevin play after the film shows, and people are just going nuts; they’re laughing and crying, and being moved by the whole thing… Film festivals want Kevin to come and play after the screening, and it’s essentially turning into a comeback tour for Kevin; he’s been collecting emails and fans along the way, so he can build the ground base for a consistent touring career.

So that’s part of why I’m raising money on Kickstarter; not only to finish the film, because it’s been a labor of love and I’ve put all my own money into it and it’s reach that point where I need a real sound mix, I need a real color-correct, some things like that, but more importantly, when the festivals can’t pay to have Kevin come, I just want to support it, and want to use that money to essentially put him back on tour.

At what point did it actually become a film? Did you bring a camera with you the first time you went to go find him, or was it after the fact that you decided this was a story you wanted to tell?

I brought the camera with me, because… in the early 90s, my brother and I were in bands, and we were thinking to ourselves, “Okay, people do have the appetite to go out and listen to music like this.” But our band was kind of popular, and we were like, “Man, if we ever make it as a band, we’re going to have Kevin open up for us, so we can provide a platform for him,” because all it takes is getting people in front of him for ten minutes, and then all of a sudden they start to see this thing they’ve never seen before.

That never happened musically, but I just started thinking as I was thinking about reconnecting with him, “Who knows what’s going to happen, but maybe, ultimately, my filmmaking will become the platform for Kevin,” and it’s actually happened.

It’s interesting because, Kevin, hanging out with him gets me more into that cosmic world, where I get out of my very structured video/filmmaking mentality, the nuts and bolts of how you get something done, and start thinking more in magical realms, and I guess part of it is I went down there with a camera because I was hoping something special might happen. For me, just personally, that’s a freeing experience to be able to make a movie, just on the fly, and to not have to analyze or think about it, to just be able to follow something as it’s happening in front of me.

I’ve always thought that I would love to do documentaries… it’s just such a money-losing proposition. Even the best documentary filmmakers, I think, make their money on commercials, and then spend it on their documentaries.

I think it’s something you only do when you find a story to tell.

Exactly.

It’s been a long road; it’s been over three years I’ve been working on this thing. It wouldn’t have sustained itself if it didn’t need to happen, if I didn’t feel just genuinely moved to expose the world to Kevin.

How did Kevin react when you first approached him about this project, when he suddenly had this very eager person on his doorstep wanting to know about him? What was his reaction?

How did Kevin react when you first approached him about this project, when he suddenly had this very eager person on his doorstep wanting to know about him? What was his reaction?

He was thrilled. He was just so happy that someone had remembered him. Part of his story, and this is in the documentary, is that he went to LA to make it, and it didn’t work out, and beyond it not working out, he almost died. It’s almost Hollywood-ish, what happened when he was out here.

Anyway, I showed up, and he honestly just did not have a whole lot of human contact at that point; he was working at UPS, the night shift, and just laying low, running at the track and listening to music. He was just surprised mostly, and just really excited about what might happen.

Then, when we went to Spain, these songs started coming to him again. He doesn’t write songs, he doesn’t sit down with a pen and paper; he just meditates and aligns himself with the universe, and it delivers songs to him, and it started happening again when we went to Spain.

I’m always interested when narrative directors switch over to documentaries, as in a way, you relinquish some of the story control you’ve had in the past. Can you talk a bit about what this transition was like for you?

Mostly, it was just freeing. Totally freeing. Mark and I have learned to thrive in chaos; it’s something the more we embrace, the better things go. That being said, there are moments of horror! When I first went to Austin and spent time with him, and I came home, I was like, “This isn’t a documentary at all. This is just the saddest story ever told, is what it is.” It’s constantly teetering on whether you have a project or not, but luckily for me, this is way more motivated by me reconnecting with him and trying to help re-inspire him than me trying to end up with a piece of art, that I could sell or use to promote myself. I mean, this isn’t going to help my career in any way, I knew that from the beginning, but that’s totally outside the motivation, so I probably had a little less pressure than most documentary filmmakers.

But, man, following someone around with a camera, watching it all in front of your eyes, and it’s all truthful, is unbelievable. Especially because of what we do in our narrative work, we’re constantly asking ourselves, “Is this real enough?” So, this project, it was all real, you know, everything you capture is very real and there was some amazing and watershed moments happening throughout the film. It was really a pleasure.

When making a documentary about a single person, you become immersed in their life. I think it’s an interesting experience for both the filmmaker and the subject, because moments that would be otherwise personal or private are suddenly shared. Was there any one moment where something happened, and you and Kevin were like, “Oh, and you’re here too.”

Mostly for Kevin; every once in a while he’d look over, because we got really used to each other, and he’d look over and realize I was filming, and he’d look at me and just smile in this way that’s just like, “Are we doing this? Are you actually filming me constantly? Is that what we’re doing here?” and I think I had that too.

For me, more for me what it was, was this guy to me was like a god, like I was a kid. Every once in a while… generally, what you’re doing is, you’re just getting down to the business of capturing this thing, it’s a lot of grunt work, and it was just me; I’m micing and shooting and trying to walk through traffic while I’m shooting him, it’s very much like a busy person’s activity. And then, every once in a while, he’d sit down and he’d just start talking, or once or twice, towards the end when he started playing again, he’d start playing, and I’d be completely sucked out of this thing and realize, “Oh my god, this guy is unbelievable and I’m sitting right here!”

There was this moment where he played guitar in a hotel room, and I was the only person in it. It just literally took my breath away, because I had forgotten that the power of what he was creating has fueled the cool twenty-year thing that I’ve been involved in. It was definitely one of those moments where you just completely get sucked out and you’re like, “Oh my god, I’m in the presence of greatness right now.”

Since docs always have so much footage that ends up on the cutting room floor, can you tell us about a segment or scene you loved that didn’t make the final cut.

There was… tons. One of the really big things about the story is Kevin’s connection to his mom. Him being an only child, his mom had tons of miscarriages before him, and the doctor basically said, “Don’t try again, you can die.” She tried again anyways, because she knew she was supposed to have a special kid. Again, this is part of Kevin’s cosmic existence. And she tried, and he was delivered incredibly premature, and they said that he was going to die. This was in the early 60s; they didn’t have the technology, they didn’t have NICU, and they sent the priest in, and she said, “Go away,” and he lived.

That was one of the things that was really tough for me to lose. There’s still some connections with his mom in there, but it was kind of a thread that, to tell the story in the most efficient way possible, the best way that we that we could, we had to lose it. There was one particular moment where he told me about when his mom died, he saw his mom, and how she came and was combing into his hair, and told him that everything was going to be okay. It was something incredibly deep and connective about that that I couldn’t figure out a way to keep it in the movie and have the same impact that we could have at the pace we’re moving. It’s not particularly a scene, it just this piece that I wasn’t about to include.

What made you choose Kickstarter as a way to raise funds?

Mainly because the documentary is an odd length; it’s about forty minutes. For festivals, it’s a great length because the film’s forty minutes, Kevin comes up and plays for like twenty minutes afterwards, and then we do a Q&A, so it feels like a feature-length screening. But in terms of the film itself, it is an odd length, and I think it will be hard to sell it for money; it’s certainly not going to get distributed theatrically. So, I didn’t feel like it was the right project to go out to investors and say, “Hey, invest in this, and you’ll make your money back,” because I didn’t feel like that was the case, I didn’t feel like they would make it back. But, I felt like on Kickstarter, people are willing to invest in more challenging things, more interesting things.

In particular, I love the nature of Kickstarter, in that my goal is to get Kevin into the world, so for me it is a win-win with Kickstarter because, for instance, at the $25 level, you get a signed CD from Kevin and a signed DVD of the movie from Kevin and me, which is pretty much retail value, if not better. In a weird way, I’ve almost repurposed Kickstarter as a distribution tool; not only do I get to raise money to help Kevin go on tour, but I get to distribute his music and the DVD into the world, which is challenging to do in today’s climate, we have very narrow lines of distribution. So, for me it was win-win; not only do we get to raise money, but I get to give away prizes, which in turn gets Kevin into the world, which is my ultimate purpose.

In particular, I love the nature of Kickstarter, in that my goal is to get Kevin into the world, so for me it is a win-win with Kickstarter because, for instance, at the $25 level, you get a signed CD from Kevin and a signed DVD of the movie from Kevin and me, which is pretty much retail value, if not better. In a weird way, I’ve almost repurposed Kickstarter as a distribution tool; not only do I get to raise money to help Kevin go on tour, but I get to distribute his music and the DVD into the world, which is challenging to do in today’s climate, we have very narrow lines of distribution. So, for me it was win-win; not only do we get to raise money, but I get to give away prizes, which in turn gets Kevin into the world, which is my ultimate purpose.

If you reach your Kickstarter goal, what do you plan to do with the funds raised? What’s next?

We are about to do our next festival blast; we just did a first blasted and ended up playing at SXSW and a few other festivals. But the next blast is going to be big, and that definitely requires some money to apply. Right now we’re already talking to Aaron Hillis who runs the reRun Theater in Brooklyn, he wants to show the film. We’re talking to just a bunch of festivals that I already have a relationship with, but thinking that Kevin is definitely going to do a tour of the east coast in the fall, just because there’s so many great festivals in the fall, on the east coast in particular. There’s nothing nailed down just yet, but we’re cooking it up as we speak.