Wake in Fright floored me. My initial reaction was simply being stunned. Then I replayed the journey I went through and I truly feel this is a rare film that not only holds up to the test of time but can have a lasting effect as well. It’s a disturbing, living nightmare film that plays with your emotions. So when I got the opportunity to speak with director Ted Kotcheff, I had to come prepared.

Thankfully, even at over 80 years of age, he seemed to have a mind like a steel trap and provided me with some fascinating tales of making the film over four decades ago. Among those insights were how Chips Rafferty refused to drink non-alcoholic beer for the shoots, the way they kept blowing tires on their vehicle, how he got called Stalin by a local and survived, and why he never forgets moments from the making of the film. Check out our interview below from Fantastic Fest for the film hitting limited re-release today.

The Film Stage: So, you’re in Austin for what? A few days?

Ted Kotcheff: Four days. There’s another screening later this week.

So you’ll be able to stay for that Q&A?

Oh yeah. Were you there at the screening?

I wasn’t actually able to catch a screening yet. I watched it online, which isn’t the most ideal place to watch a movie like this.

You’ve got to see it on the big screen.

But if you’re standing inches away from your screen, and you got your headphones in…

[Laughs]

And it’s late at night and you turn off all the lights, you get some atmosphere.

You get sucked into it!

Oh yes. But, so, you’re in Austin for four days. Do you come here with an idea of, ‘I’m here for business, but I want to do this and this?’

Well, the last time I was here was 30 years ago. In 1980 I made a film in Dallas that was called Split Image. Michael O’Keefe was in it with Karen Allen and James Woods. It was about a boy that got sucked into a cult. James Woods is a deprogrammer of kidnaps at the instigation of his parents. I was making that film and someone on a weekend said, ‘You should go see Austin. It’s a very nice city. And you can also go water skiing. They have a lot of lakes.’ So I came up here with my wife and spent the weekend. That was 30 years ago. When I arrived two or three days ago, this city was hardly recognizable from the city that I experienced. It’s changed so much. All the buildings have gone up. It was like a nice small city. But now it’s become a metropolis. [Laughs]

It really has. It’s blossomed. So you’re talking about a film you made four decades ago. So when you come into this situation where you’re going to be asked questions about this, do you do any research into your own film? I mean, it sounds odd but to get back into that headspace… do you just watch the film again?

Well, I’ve got a pretty good memory for my experiences. Bill, making a film is such an intense experience. And you think of nothing else except the film. You’re shaving. You’re going to the toilet in the morning. You go to be at night. You dream about it. It’s endless! And every scene I would think, ‘Oh, I’ll do this and I’ll do this.’ You have visions of it. And the emotional experience… it is so all-encompassing, so all-absorbing, and so intense that you never forget it. I never forget it. I remember every moment of the experience. [Laughs] It’s so imprinted on my memory. But at the same time, I did a little. For example, some people ask me about the reviews. And I keep my reviews. I went through and looked at some of my reviews by Pauline Kael and some of the others. But that’s the only kind of research I did to see the reactions when it opened in New York.

That’s a great thing I was planning to ask you about. What are the most common reactions you have received? Not good or bad, but the specifics of the film. I can only imagine the kangaroo scenes are probably frequently commented on. Maybe not back then, but especially now.

Oh, it was worse back then.

It was?

Oh, yeah. United Artist kept saying to me, ‘Ugh, no one is going to be able to see this film because of the kangaroo hunt.’ Americans especially have pets. And I said, ‘Well you’ve got to put a sign up saying, ‘No animal was specifically hurt or killed.’

With the intention of this film.

Yeah, for this film. And I said, ‘Done under the auspices of the Royal Australian Prevention of Cruelty To Animals.’ And we got their seal of approval. And I said, personally, I don’t hunt. I don’t believe in killing an animal. To kill an animal for a film, to me, is horrendous. Totally immoral. It’s bad enough to shoot an animal to eat it. But to shoot an animal for a film? I couldn’t do it. So yea, it was hard to take. But it was harder to take then than it is now. It’s been more accepted now. But I know people have had problems with it, no question.

There’s a lot of tension and intensity within this film. Is that something that translates from you on set or is that just built in editing? Is it an intense set?

Well, that’s a very difficult question to answer. But yes, there’s no question I empathize and enter into the atmosphere of the film that I’m making. I empathize with the characters. So yes, it certainly reflects my own feelings about these things. And at the time I was pretty despairing about human beings and the Vietnam War and the threat of nuclear destruction. It was the first time human society was capable of committing suicide by blowing themselves up. I said ‘human beings, they’re just broken pieces of machinery. They just don’t work.’ [Laughs] This picture kind of reflected that slight despair. So it was my own personal feelings about it, yea.

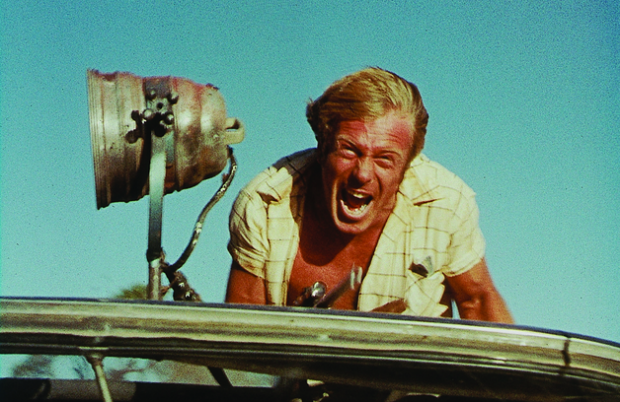

There’s some great sequences where you take this vehicle out into the desert and just run it ragged. I’m seeing this thing bounce around and in my head I’m thinking ‘you got to break an axle. Break a wheel.’ Were there something with that particular vehicle?

No, the only thing we did was we blew tires out all the time because the Outback has these very sharp, flinty stones. I mean, when we were looking for locations, we went out in a vehicle and we blew a tire. About 30 miles outside of Broken Hill. Way out in the middle of nowhere. So, we changed it and put the spare on. Twenty miles later, we blew the spare. Now we were stuck out there. In the heat, you had to be careful. You wait. You sit and you wait. Finally a car came. No cell phones back then. A guy comes along and he says ‘what’s the matter, mate?’ And I said ‘well, we’ve blown two tires.’ ‘Oh, I think I have a tire here that will fit you.’ He gets the spare and says ‘here it is.’ And I say ‘how can I pay you, sir?’ ‘Pay me? Naw, you aren’t going to pay me. Next time I’ll be in the same trouble and you’ll help me out.’ He was so generous. That’s what I admired about those people. They supported each other because the circumstances in which they lived and worked were so inhospitable, you had to support each other. Everybody. The whole community. That was a strong characteristic of those men back then. As well as the darker side that I show in the film.

Did that experience lead directly into the film or did you already have that kind of generosity built into the film?

Yes, I did. I understood. It revealed itself in the hill, again, that aggressive kind of hospitality. And that’s what you think about.

‘You’re going to drink this beer.’

Yeah, that’s right. And also they took him in. ‘Oh, yea, don’t worry about it. You can stay here.’ They were free and easy about that. So that side is kind of revealed in that. But yes, they made you drink beer.

I’m also curious about that. There’s a certain amount of movie magic that goes on in making films. But was that actual beer you were guzzling?

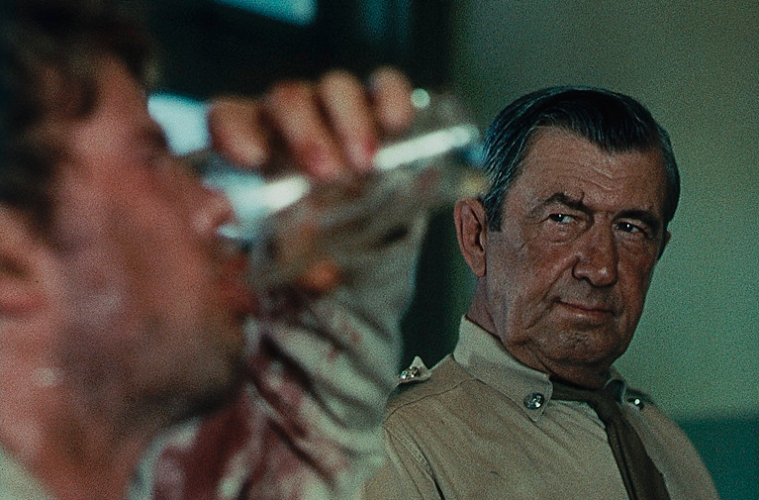

Well, there’s a very funny story that I’ll tell. Two stories, actually. First of all, the Australian cop, Chips Rafferty? He was a very well-known Australian star. He starred, way before your time, in a bunch of Australian westerns. They played in England. Never came to America. He was a terrific man. Terrific actor. But, of course, there was a lot of beer drinking. So I had a lot of non-alcoholic beer from the props guys. The first time he sipped it, Chips said, ‘I ain’t drinking this. This is non-alcoholic beer. I ain’t drinking this! This is fake! I can’t act with fake beer.’ So I said, ‘But Chips, I do six or seven takes and you drink a whole pint in one gulp. Every take, you’re going to drink six pints? How are you going to get through the day?’ ‘I tell ya, that’s my problem, not yours.’

[Laughs]

He was the only actor in the film that drank real beer. Never, ever got drunk. Never, ever slurred a word. And sometimes he would drink 20 pints a day, I swear to you. The other experience with alcohol there was with Donald Pleasence. Did you like his character?

I loved his character because in normal society, he’d be an outcast. But there, he’s just one of them.

He says ‘I’m an alcoholic but it’s hardly noticed out here.’ [Laughs] But anyways, there’s this scene after the kangaroo hunt where they’ve been drinking whiskey and he’s drunk. He talks to Gary Bond and keeps calling him Socrates. The other two guys are having a fight and he joins in and smashes up the whole place. He says ‘Ted, it’s just so hard to do that scene. Demonic alcoholics. They are really drunk and out of control. I’m not sure I can play it sober.’ I said, ‘Oh, come on, Donald. You’re a great actor. You can do it.’ We were very easy with each other. Like I said, we were very good friends. But he did it. He said ‘OK, I’ll try.’ And he did it. It was very good. But it wasn’t gripped when I saw the dailies the next day. So I went back to him and said, ‘Donald, I made a mistake. You were right. Get drunk. And we’ll do it again.’ And this time it was flawless. It was the only time any other character but Chips Rafferty drank alcohol. But you know? Boy, out there, I drank a lot of beer. Because the water’s undrinkable out there–supposedly. Only good for the sheep. And it’s so hot, so you’re continually thirsty. Continually drinking. I drank quite a bit of beer myself during the course of shooting. [Laughs]

Can you talk a little bit about the locations you shot in and how hospitable the locals were?

Well, the book was set in this town called Broken Hill. Which was way out in the middle of the Outback. Surrounded by hundreds of miles of nothing. Those vast spaces. The vast emptiness: it wasn’t liberating. It was claustrophobic and imprisoning. You felt imprisoned by this space. The people out there… first of all, the life is so simple. They work in the mines or the cheap ranches. And I participated in the twop-up, the game they play where they throw the pennies up in the air. Another member of the crew and I used to play every Saturday night. Nothing else to do in that town. They welcomed us everywhere. They loved us there. To this day, I mean, when I was there two or three years ago, they pleaded with me to come back out with them. ‘Oh, we loved you. Man, we remember you. Dah, dah, dah.’ Of course we celebrated the town itself. Are you game for a story?

Yeah.

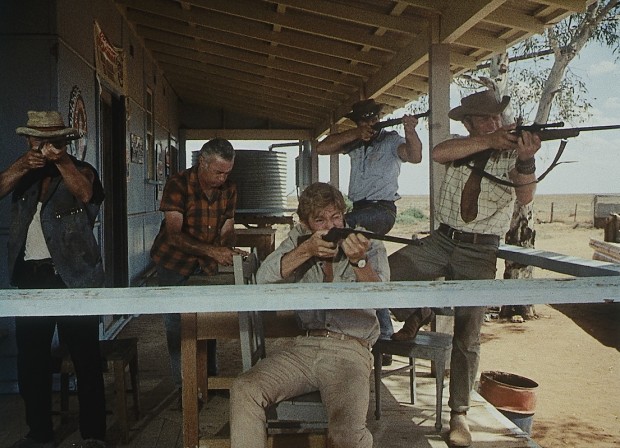

I’ll tell you a story. I was scouting for locations and I wanted to find a pub way out in the middle of nowhere. We were driving along and suddenly I saw this place. Way out. You could see about 50 miles there. ‘Look at that building with a 30-foot beer bottle on top. Let’s go!’ So we just go right off the road, across the Outback. Bumpity bumpity bumpity. And we arrive at this place. It was a Sunday. And there were about 30 cars and it was 110 in no shade. In each of the cars there was a woman. Usually blonde women, with beehive hairdos, which was the fashion then. Of course, they’re not allowed to go inside. Their husbands; their boyfriends; their brothers, they’re inside. I said ‘Wow, this is great. Let’s go inside and let’s see if I can use the interior.’ John Shaw, the Australian location manager said, ‘You know, Ted. Let’s come back tomorrow.’ When they’re down the mines and back on the sheep ranches. I said, ‘Well, why? We’re just going inside to have a look. We can’t have a look? Drive 40 miles tomorrow in the heat?’ And he said, ‘Look, Ted, to be frank, they don’t like outsiders very much around here. But they especially don’t like outsiders that look like you.’

Because at the time, I was a ’60s hippie. I had a handlebar mustache. And my hair was down to here. *Points below shoulders* The full ’60s look. And so I said, ‘What!? They’re going to hit charming, old Ted Kotcheff? Naw, naw, naw, naw.’ He said, ‘Well, if you want to go in it’s your funeral. I ain’t going in with you.’

[Both laugh]

I said, ‘Pfft, that’s ridiculous.’ I get out of the car, took three steps, and thought, ‘Jesus, John Shaw, he’s built like a brick shithouse, and he’s scared to go in, and you’re going to go in?’ But by this time I had committed myself, so I go inside, right? I walk inside. Forty pairs of drunken eyes–it’s like a Western–they all went silent and they watch me. So I crossover to the bar and I said, ‘I’ll have a schooner of ale, please.’ They all went back to their conversations. And I drink it. But there was a guy about six feet away from me. He looked at my hair. Then he looked at my mustache: ‘Shiiiit’. He looked at my long hair again: ‘Shiiiiit’. And finally, he said to me, ‘Hullo Stalin’. So I didn’t say anything. I just toasted him. With a loud voice that quieted the whole room down, “I said ‘Hullo Stalin.'” Inviting a response. ‘Who the fuck are you?’ He put his jaw right in my face. He didn’t want to him me. He wanted me to hit him. So I kinda smiled at him and I said: ‘Listen, I’d love to talk to you, but I’m dead.’ He didn’t get it for a couple of seconds–the whole room didn’t get it at first–then they got it and they all laughed their asses off. He said to me: ‘I love a bloke with a sense of humor! Give this man a schooner of ale!’

And those guys became my friends. They looked after me. I did a lot of research: going to bars; talking to people so you get a feeling of the whole town and the inhabitants down. And somebody would inevitably come up to me and want to fight me. ‘Come on, let’s fight.’ And I’d say, ‘Eh, I got no quarrel with you, mate. I don’t want to fight you.’ ‘Oh yes, come on. Let’s fight.’ And a voice would come from a mob of people, ‘Hey, Joe, you leave Ted alone. He’s my mate!’ ‘Oh, sorry. Teddy, how about I buy you schooner of ale?’ There was no animosity and these guys looked after me. Six of them. Wherever I went, there was always one of the guys. Watching me and making sure I didn’t get hurt. Now that was a curious male society. This camaraderie that existed. It’s important that they offered it to each other. They knew what a difficult world it was out there. But back in the pub, which I call the Stalin Pub, we all laughed. They all got around and they kept buying me beers and I bought them beers and talking and talking. Meanwhile I left John Shaw to cook in the car outside. ‘No guts, no glory. I’m staying in. I’m not bringing you in here.’ All these guys became my chums for the next three months. They looked after me.

Wake in Fright is now in limited re-release.