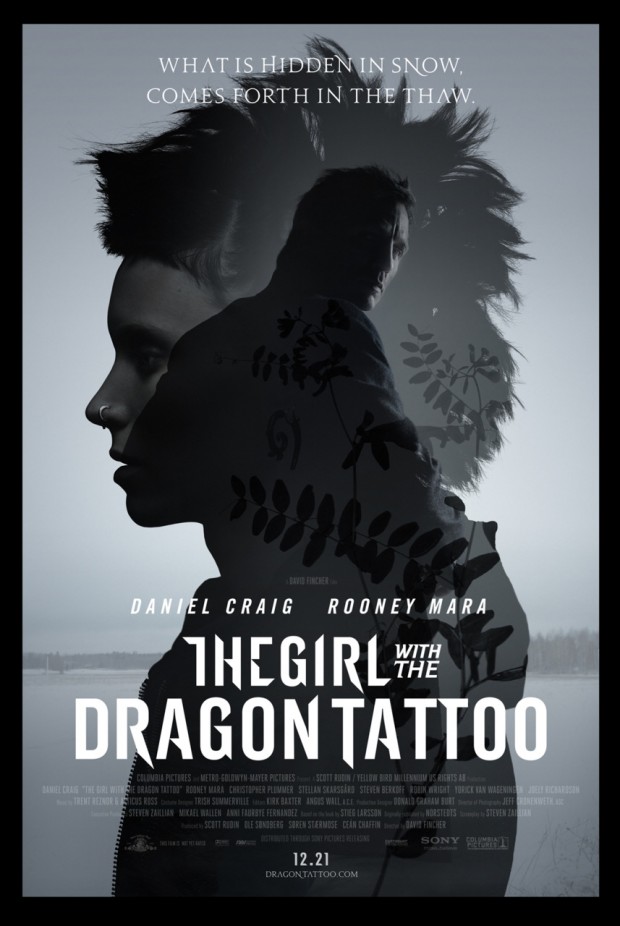

Earlier this year, musician Trent Reznor and composer Atticus Ross rightfully received an Academy Award for their original score for The Social Network. Their collaboration gave the film a propulsive feel, helping the drama move as efficiently its protagonist acts. With The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Reznor and Ross once again collaborate with director David Fincher for a much different and much bigger film.

Reznor and Ross’ score is epic, soon available on a 3-disc set and currently available online. Even while listening to the score separate from the film, the tension and chilly mood it creates is palpable. Like The Social Network, it’s a score that works wonders as a standalone piece.

Here’s what artist Reznor had to say about the long process of scoring Dragon Tattoo, the respect and meticulousness of Fincher, and determining success and failure:

I’m guessing you’ve seen the film a hundred times now?

I’ve seen it a few times, yeah.

Does it stay exciting or does it get a little tiring?

[Laughs] I mean, we worked on this for so long there was a time where it was really impossible to maintain any objectivity. It really wasn’t until I got to see the almost, almost, almost finished version up at Skywalker a couple of weeks ago… I gotta admit that was the first time — and I had seen it assembled many times — but to see it with another layer of polish, the right audio mix and the right space, I got that charge like I had never seen it before. It was a nice experience.

The album itself is epic in length. When you took this on, did you know what kind of undertaking it was going to be?

Well, Atticus and I made the conscious decision to really leave this last entire year open for this project, not take on any other work and not try to spread ourselves too thin, because we assumed it could branch out and there was a lot of stuff we had to do. Going into it with that kind of mindset, it wasn’t a surprise when we really got into it we saw we had a lot of ground to cover. It was a fun experience, and an in-depth and detailed one. It’s nice coming down and seeing the end of the tunnel now, since we’re proud about it.

You mentioned how it was tough maintaining objectivity. When you do lose objectivity, how does that affect the process?

We started off thinking, “Let’s just stay very abstract and very impressionistic,” and when we didn’t even have the script. I had read the book and spoke, in detail, with David [Fincher] about the kinds of soundscapes, emotions and whatnot, then we just blindly composed for six weeks this time last year. We composed music we felt might belong, and then we’d run it by Fincher, to see where his head’s at. He responded positively. He was filming at this time last year and assembling rough edits of scenes to see what it feels like, and he was inserting our music at that point, rather than using temp music, which is how it usually takes place, apparently. Getting into this year, when we finally started seeing scenes and digging into the sequence of shots, where we’re seeing things out of context and out of continuity, it gets pretty hard, especially for a film this long. You try to remember, “Oh wait, this comes after those ten things and comes before that,” so we have to be considering of that and the mood we’re trying conjure up.

So the difficulty was finding the structure of the score?

Yeah, we weren’t working on a finished thing, so everything keeps moving around, scenes are changing in length, and even the order of things are shuffled around — and that can get pretty frustrating when you get precious about your work. It was a lesson we learned pretty quickly of, “Everything is in flux, and approach it as such. Hopefully it’ll work out in the end.”

Was it a much different process from The Social Network?

We officially came on after it was shot, and it was pretty much edited to recognizable form. You could watch it and it flowed like a film. We knew what we were up against at that point. There was a structure, and that structure didn’t really change. Things got a bit polished, but there wasn’t kind of a real… we knew the scenes that were going to be in the film, that kind of thought. With this one, it was much of things in play, a longer movie, and much more to consider.

Working on another score obviously means you had a positive experience with The Social Network. On an artistic level, what did you find satisfying about scoring that film?

It forced me to compose in a way I had never thought about. It forced me to work for a different purpose and master. You know, if I’m working on my own music, I’m hoping that’s 100% of your attention. In the role of film composer, I realize I’m working on what’s best for the picture and helping realize David’s vision, and that was a refreshing change. I didn’t look at any of that as a series of restrictions; it was more like an interesting exercise and an interesting process. I think the key to that working was a mutual respect between David and I, which we very much have. It was fun not being the boss for a change and fun getting into his head, and helping him realize what he saw and heard there. The same thing followed over to this film, to a more extreme degree. We were much more involved in the process on this one.

Does going off of someone else’s vision versus creating your own make the process — I hate to say easier, but is it?

I wouldn’t say easier, it’s different. Usually when I’m working on a piece of music I would think generally, as opposed to, say, Paul McCartney or a real traditional songwriter who starts with a melody, words, and then arranges it in a certain fashion, a lot of times I find inspiration from the arrangement of the texture or the setting. What I’ll do, if I’m composing for Nine Inch Nails or How to Destroy Angels, is visualize something — a place, a feeling, an emotion, or some scenario like that. I’ll start to try to see what it sounds like, to get a feeling evoked, and then insert a melody and lyrics inside that frame. So this process wasn’t radically different from that, except I’m being told what the scenario is, rather than conjuring up. The pro of that is, “Oh, I can literally see what I need to make come to life.” In my world, if that scenario kind of sucks, I can throw it out and conjure up a new one [Laughs].

[Laughs] I thought your writing process would be similar to working on this, since the film relies heavily on atmosphere.

Yeah. I started off thinking… you know, my fear with The Social Network was: How the hell do I score that? [Laughs] When I’m looking for inspiration, I’m usually not conjuring up entitled assholes arguing about shit in courtrooms. I thought when The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo came up, I thought, “Great. I see landscapes, terrible scenarios, and stuff I can understand.” You realize once you get that out of your system, in the first ten percent of the process, you think, “Now what?” It’s not really about the icy landscapes; it’s about what these characters are feeling, and what we’re implying they’re feeling and getting into their minds. It was a much more difficult — and maybe just because it was a longer process — than dealing with The Social Network. I think we had so much opportunities and time, we backed ourselves into corners quite often.

When you get into one of those corners, what do you do?

When you look at some of our composer brethren — who do six or seven films a year — I envy that, in some ways. In some ways, I’m mystified at how you can do that, and do that with depth. I don’t think I could do that. If I had to, I think I could come up with something. We really became this film. We lived with it, thought about it, overthought about it, woke up thinking about it, and dreamt thinking about it. We kind of inhabited these characters, and composed fully involved in that. Having the time to realize when something isn’t the right direction, we’d have time to fix it. That was comforting. Also, we’re new to this — the whole world of film scoring. We really didn’t want to fuck this up, so we gave ourselves time to fix things.

I was surprised to hear you say what you thought about writing The Social Network, and not the part of not thinking about entitled assholes arguing [while writing]. I’m betting you could relate to what it’s about: the process of creating and the pitfalls of ambition.

You’re right — that’s what the movie is about. I think my first fear was, “Oh shit, I’m not seeing dragon slaying and serial killers.” What is the sound of, you know, what I described earlier? On the surface, it felt like that. It was the first panic moment of, “What’s the music going to sound like?” It wasn’t obvious, but I quickly realized what the film is about isn’t the setting; it’s about exactly what you pointed out, which I do have a lot to relate to. I could empathize with the characters in that film, in a lot of ways.

You labeled the process of The Social Network as a “reinvention.” How does The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo fit into that reinvention?

A reinvention of myself?

Yeah.

I think it’s more in the world of refinement. The Social Network came out of nowhere in my life. We worked on it fairly quickly, and we didn’t have a lot of time to second guess, question ourselves, take classes on how to score films and do quick internships with people who know what they’re doing. The combination of scenarios involved and the loving guidance of Fincher led us into a place where we felt experienced. The accolades we received for that were unexpected and flattering, truly. Going into this, we took on a bit different mindset of, “Let’s sort of figure out what we’re really doing here. Let’s consider those things, have time to think things through, and explore possibilities we may not have had the opportunity or the knowledge of the first time around.”

What were some of those lessons?

Probably the biggest lesson of this — and I’m saying this as someone who’s scored two films — I’m looking at this, and Atticus shares this view, as trying to contribute to this piece of art. We’re a part of the support structure of what makes this piece of art something that is as great as it can be. Seeing the filmmaking process for the first time in-depth — and I understood how things get put together and made in the process of film — but seeing the people working and how David interacts with his editors, and the construction process behind there, and the role of music in that, which generally is to throw temp music in there to get the soul of the picture, and then hire a real composer to replace that music with a real score. Composers like that, because it limits their time on the film and they’re working on a finished film, which is essentially what we did on The Social Network.

The film was pretty much finished, in terms of its structure, and then we had to put music into these scenes and put life into it. Seeing it from a composer’s point-of-view, it’s a pretty elegant way to work. You’re not endlessly revising things, writing stuff that doesn’t go into the film, and redoing passages because the length of a scene keeps changing. Now, the order of a scene has changed, so then the most beautiful piece of music you’ve ever written is now half the length or gone, and we didn’t experience too much of that on The Social Network. Seeing it through the eyes of a filmmaker and what would be a good asset for them to have, it makes sense to me that, when they’re filming a scene, if they have music to fit that scene, that could be asset to Fincher and the editors, to see it with what would really be in there. We decided to give a lot of music early on, without specific intent in where it was going to wind up.

The film was pretty much finished, in terms of its structure, and then we had to put music into these scenes and put life into it. Seeing it from a composer’s point-of-view, it’s a pretty elegant way to work. You’re not endlessly revising things, writing stuff that doesn’t go into the film, and redoing passages because the length of a scene keeps changing. Now, the order of a scene has changed, so then the most beautiful piece of music you’ve ever written is now half the length or gone, and we didn’t experience too much of that on The Social Network. Seeing it through the eyes of a filmmaker and what would be a good asset for them to have, it makes sense to me that, when they’re filming a scene, if they have music to fit that scene, that could be asset to Fincher and the editors, to see it with what would really be in there. We decided to give a lot of music early on, without specific intent in where it was going to wind up.

Initially, coming from an impressionistic point-of-view, we created a library of music covering a bunch of different moods, so we could collaborate with David and the editors early, to see, “What do you think for this kind of scene? Oh, we think this is better. Now check this out, we’ve modified it for X, Y, and Z.”

It was a much, much more collaborative and interactive experience. Also, it was much, much, much more work and many more times of realizing, “Oh, it’s a more collaborative way of working,” which means it’s not always the way you think it should be. We learned a lot that way, and it was an interesting process and I think the results turned out great. You know, it was a whole 14 months of our lives working pretty much everyday, and that’s also why the soundtrack record is long. We just kept writing music. There’s more music than there is in film. We thought, ‘This was all written for this specific purpose, so they all feel like relatives, as songs. Let’s put them out as batch of what we did this year.”

Since it was a very long and collaborative process, what creates that trust between you and Fincher, for you to believe he’ll make it all work?

It’s really his respect. Before I even worked with him in a scoring capacity I had just been a fan of his films. I like his aesthetic. He’s someone I’m genuinely excited about, for what he brings to the table as a director. When he asked me to work as a composer, I went in not knowing him that well as a person. I never interacted with him very intensely, other than on the set of a video. I gain an enormous amount of respect to see someone who takes what they do as seriously as I take what I do. Not to sound arrogant, but I find quite often I run into people who think I’m a prick or difficult to work with. I expect excellence, and I demand it. If we’re going to do this, let’s not fuck around, let’s do it. Then let’s do it a little bit better, because why would you not do that? What’s the point of it if it’s not the best work you can do? I found someone that may have up the ante on me with Fincher. He challenges you and sometimes provokes you, but I have complete faith in what he’s after is excellence. I believe in his vision, support it and respect it, and I feel the same affinity from him towards me. It’s led to a good working relationship. It’s not always, “Let’s hug each other! Yeah, I agree! Great, I love that too!” Quite often, we’re butting heads about certain things, but it’s with respect.

What I’ve learned from him is often he doesn’t tell you the whole story. Like, he suggested Immigrant Song, ‘Trent, how would you feel about an aggressive cover of Led Zeppelin‘s Immigrant Song, maybe with, I dunno, Karen O wailing over it?’ Now, if you asked me how I’d feel about doing that for Nine Inch Nails or a single for my career, it wouldn’t be the top choice. I like Zeppelin, I like that song, and I really like Karen O, but that’s not particularly where I think my trajectory is headed. I’ve learned with him to say, “Um, let’s see.” What I didn’t understand at the beginning of that was he was hearing that as the teaser trailer for the film. Ultimately, and as you’ve just seen, [it’s in] the title crawl, and I think it works great. I didn’t feel that or hear all that, since he didn’t explain all that. He maybe didn’t even known all that back in that time. When we strongly disagree on something, in terms of music to use in the film, four out of five times he’s usually right, since he’s seeing it through the eyes of a very zoomed out version of how the film looks, while I’m seeing it through, “Well, what about this piece of music in this scene?” Well, that doesn’t really matter, since it follows these other pieces of music in this other flow he’s seeing, since he’s seeing all of the parts put together. I’m the technician, he’s the guy with the overall vision.

One of the five times he’s not right, what do you do?

Out of one of the five times that he’s not right, I speak up and he generally takes the time to realize I’m right, because I’m always right [Laughs]. No, like I said, there’s a respect where we listen to each other’s opinion. We’ve learned when to make a stance about something. If he strongly feels one way, great, it’s going to go his way. If I strongly feel there’s a reason it shouldn’t be something, I’ll make a point and insist on that until we work it out. Generally, he’s very receptive to that kind of input.

How do you judge a success or a failure? Is it based on your own personal feelings or how others react to your work?

The time old question. Most artists will tell you it doesn’t matter what others think, and it matters what you think once you finish it. I’d like to say I believe that, but, in reality, I can look back on my own work and feel great about something, then it gets critically shit-canned or someone hates it, and that’s the one that sticks with me [Laughs]. I feel like I’ve failed somebody. The public’s reaction to something can often taint your experience, and I try not to put too much weight on that. It does make its way into your process, and particularly in this information-driven world we live in, where everyone’s found a way to express their opinion. At the end of the day, what really matters when you’ve finished a project is that feeling of, “Hey, this is the very best I can do, and I’m proud of it,” and I don’t think I’ve let anything out I haven’t felt that way about. What the public thinks of it, in retrospect and hindsight, hasn’t always agreed with my opinion, but it has to past that muster, for me, to let it out. I know Fincher feels the same way. I know he feels strongly about everything he’s done, and that he poured his heart and soul into it, speaking for him.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross‘ soundtrack is now available. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo hits theaters December 21st, 2011.