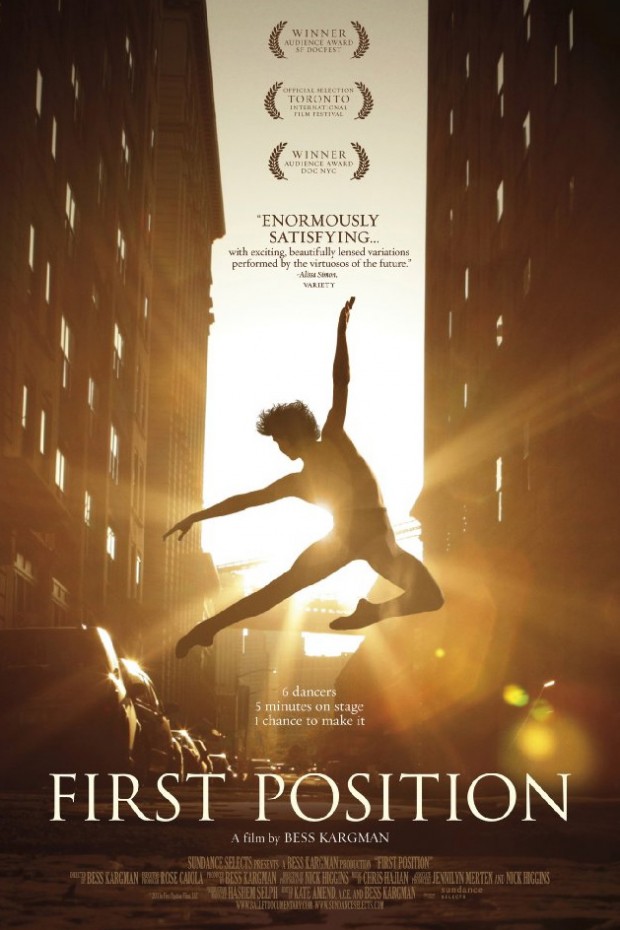

Ballet has cemented itself in my mind as of late. I’ve made it no secret how much I truly admire Black Swan while The Red Shoes sits atop my top five all-time list. Although I wasn’t anticipating a documentary on the subject, I was proven wrong, as First Position is a wondrous journey behind the scenes of the elite youth Grand Prix. The competition occurs every year and decides the fates of hundreds of ballet dancer hopefuls. First-time director Bess Kargman was gracious enough to sit down with me to discuss the film and we covered such topics as why the individual subjects never interact on camera, her efforts to show diversity in this sport of preconceived notions, what surprised her the most about the process as a newcomer, choosing the subjects, and much more. Check it out below.

The Film Stage: One thing I found fascinating about the film, and documentaries in general, is when you bring in all of these different characters, sometimes they allow things to happen that isn’t part of the script. Yet all of your subjects make it into the Grand Prix, obviously. But you’re following them up to that point. Did you have try-outs? How did you figure on these select people or were there other people that didn’t make it into the Grand Prix?

Bess Kargman: Well, I would have loved to have had someone in the film not make it into the final round because that’s true life. That’s the drama. That’s the reality of entering a competition. However, perhaps the one con to a director having danced her entire childhood and being able to spot talent, artistry, grace, maturity, and having that special something on stage that few young dancers have at that age. The one con to that is, well, that’s what the judges spot.

You’re saying, ‘This person’s good.’

You’re saying, ‘This person’s good.’

I’m saying, ‘I haven’t seen anyone dance like that in a while. Whoa!’ When I set out to make this film, I really didn’t think to myself, ‘Are they going to win? Are they going to win?’ That’s not what I thought about. I thought [about whether] they have something so special on stage that even non-dancers can appreciate it? Because sometimes people ask me [if] I made this film for ballet lovers. And the answer is no, not really. And I’ll tell you why: I know I will get the ballet loving crowd on my side. It’s the people who are dragged to the theater who I want to win over. And I want to surprise them. I want to make them laugh. I want to teach them about dance, and I want it to be dramatic. Those are the things I set out to do in my storytelling but also, other than talent and uniqueness on stage, I decided that the most difficult thing about doing a competition documentary is that if you’re solely trying to predict who will win then you’re risking the entire film’s success on outcome. And that’s something you have no control over.

How do you maintain more control as the storyteller? You cast young dancers whose personal stories, personalities, and offstage lives are so special, unique, and surprising that even if the last five minutes of the film bomb and no one does well, the first 85 minutes of the film people are going to enjoy. And they’ll become invested in the dancers. But when it came to who I wanted, for example Jules, he’s not so talented. And if I really only cared about results, I wouldn’t have put him in the film. But far more interesting than having everyone be perfect is a brother/sister duo. It’s fascinating to me. You have an older sister who’s so determined and driven and then you see a boy who kind of would rather play video games.

Yeah, he’s kind of dragged into the narrative in a way. And in the press notes you mentioned that you wanted to show that not everyone is this psycho mother, kind of living her fantasies through her children.

My advice to aspiring dancers who want to make it as professionals, is do not do it unless it is literally the only thing you can think of doing. If you are trying to decide between dance and a few other things, only do it for fun. Don’t try and make it. Because it’s too difficult. It’s taxing on your body, it’s taxing on your mind. You have to be so, so, so dedicated. Common perception is that young, very serious dancers, ‘they give up their childhood and gah, that’s so depressing. How could their parents allow them to do that?’ And what you find in this film is that it’s way more complex than that. None of them feel like they’re giving up their childhoods. Even if they haven’t been to a birthday party in three years. They wouldn’t say that. Miko doesn’t have any problem with the fact that she now does schooling at home online in order to spend six hours a day in the dance studio. She never complains about that. And I think the audience is very surprised by that. I think the audience usually goes into a film going, ‘The parents are going to live their dream through their kid. The kid really, secretly hates this. And they’re being denied all of these normal, childhood things.’ Like going to normal school. Having recess. You know. But with Miko, if her mother said, ‘tomorrow I’m not taking you to ballet,’ Miko would say, ‘fine, then I’ll walk.’

She would find a way.

She would find a way. And that’s the same thing with a lot of the other dancers in the film. It’s just the only thing they’ve wanted since the age of four. And that’s very inspiring, I have to say. I had a doctor come up to me and say, ‘I don’t even like ballet, but the reason why I love this film is because, A, the dancing is incredible. And you don’t have to like ballet to appreciate the dancing, but B, most importantly, this has inspired me to go into an area of medicine that I’ve always wanted to go into but haven’t had the courage to take that huge risk by veering away from the field of medicine that I’m comfortable with and know the best. If these kids can take such risks, work so hard, and give up so much for their dream, why can’t I start taking some risks in my career as a doctor?’ I thought that was so interesting that you really don’t have to love ballet to have this film resonate with you.

Absolutely. You definitely draw in the audience. I don’t have any kind of background in ballet. I wouldn’t say I have a displeasure for the art, but I don’t necessarily look at it as other people might. It’s enrapturing to watch these people dance and their lines, it’s just beautiful. One thing I found interesting is that you have this group. And they’re all barreling towards this one competition. In the same place. And yet you don’t have them interact. Was that a conscious decision? Was it just something that happened? And did they know about each other?

Interesting questions. So, one word of advice that I got from very experienced filmmakers when I was going into this project was exactly to do what I didn’t want to do. They would say to me, ‘You must pick one age division, kids who are all the same age, because you want to have them competing against each other. The drama. The tears. The backstabbing.’ When you put them into the same age division, there’s a tendency for things like that to happen. And I strongly felt that it would be far more interesting to chronicle the lives of young dancers who are anywhere from the ages of 10 to 17 to show how the stakes differed depending upon your age. To me, I really thought that I would be able to make the film dramatic even if Girl A wasn’t an enemy or competing with Girl B. And the main reason you don’t see them interact that much is because A, you’re sort of in your own little world when you compete. You really are just focusing on yourself. And B, they canvased three different age divisions.

And gender as well.

And gender! I wanted this to be a very gender-neutral film. That’s why I picked as many boys as girls. But if you have competitor number 400, and the next dancer in your film is competitor number 620, they don’t overlap. You’re filming them either on a different day or five hours apart. So, they all know each other. They like each other. They have become closer now because they are all in this film. So they’ve come to screenings together. But they’re all pretty different and they all live in very disparate parts of the world. They won’t see each other that often but they keep in touch.

You have a background in journalism. So I’m curious, from your perspective, coming to this from the outside looking in and then being on the inside, what kind of stood out that you didn’t realize… I mean, this is your first film. What really surprised you?

Well, let me think because this is an interesting question and I don’t ever recall being asked this. In retrospect since?

The production, really.

I didn’t fully realize how dramatic the film would be, and I’ll tell you why. When you are filming these things, and you’re filming 12 hours of footage a day, you’re not specifically focusing on ‘What’s going to be most dramatic.’ Like, on the day where Miko fell, the reason that it wasn’t all that dramatic for me was because she got up so quickly and she danced through it and then she changed and went and performed something else and then it was like, ‘Yay, she did a good job.’ But what’s so interesting is that every time I watch the film now, as an audience member, not as a… I had a job. I was there to film. I wasn’t there to assess the results, I was there to be a documentarian. And now as an audience member, I’m biting my nails, I’m so nervous for them. I’m rooting for them. I get verklempt when emotional things happen, and I didn’t realize I would be affected as much as an audience member who’s never seen it before. Now that I’m less of the filmmaker and not in production anymore, I get to be in the audience watching it, I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh! This is so dramatic!’ Even though I know what’s going to happen to the kids, I’m still terrified for them. Even Michaela. She said that the first time she saw the film, ‘I know what happened to me and yet I’m so nervous for myself right now.’ So, that’s exciting. Experiencing the film the way the audience does and not as the filmmaker.

I want to go back real quick. You mentioned that you go a lot of advice to get the backstabbing. And you went away from that. Were you nervous or did you just feel in your gut, ‘No, that’s not what I want’?

I attribute part of it to my background as a journalist but I really think that I would have been embarrassed by my work product if one of the kids came up to me after seeing the film and said, ‘You know, I regret being in this. And not only could you affect my career in a negative way, but I wish I had never met you.’ I just wouldn’t be able to sleep at night if someone had come up to me [and said that]. What I think is so much more powerful is when a person comes up to you and says, ‘You accurately portrayed me. Thank you.’ They never said, ‘How come you didn’t only show the perfect parts of my…’ Miko never said, ‘Why did you show me fall?’ Rebecca never said, ‘Why did you show me upset in the dressing room?’ Because they know that’s real life. That’s drama. It’s got to be in there. But I would never just show the bad stuff or just show the times when a person’s crying. You really have to accurately portray what’s really going on. I think there were other ways to make it really dramatic and suspenseful and add tension without it being so-and-so talking badly about so-and-so.

I always had the intention of my audience being adults. But what I never expected was how many kids love it. My nephew, he’s five years old, he sat through the entire thing without asking to go pee. That is a momentous event.

[Laughs]

He can’t sit for 12 minutes.

And that’s an audience member that isn’t going to lie.

Yea, totally.

He’s going to fidget or…

It doesn’t matter that I’m his aunt. He will leave when he wants to. And he enjoyed the whole film and one reason that I think a five-year-old can go to this film is because there isn’t that backstabbing. No one’s talking smack about someone else and you don’t need it. But I know it exists in the ballet world. I know that it happens. Stereotypes exist for a reason, I just didn’t want to put my name on that. So I figured out a way to work around that.

First Position is currently in limited release and expanding.