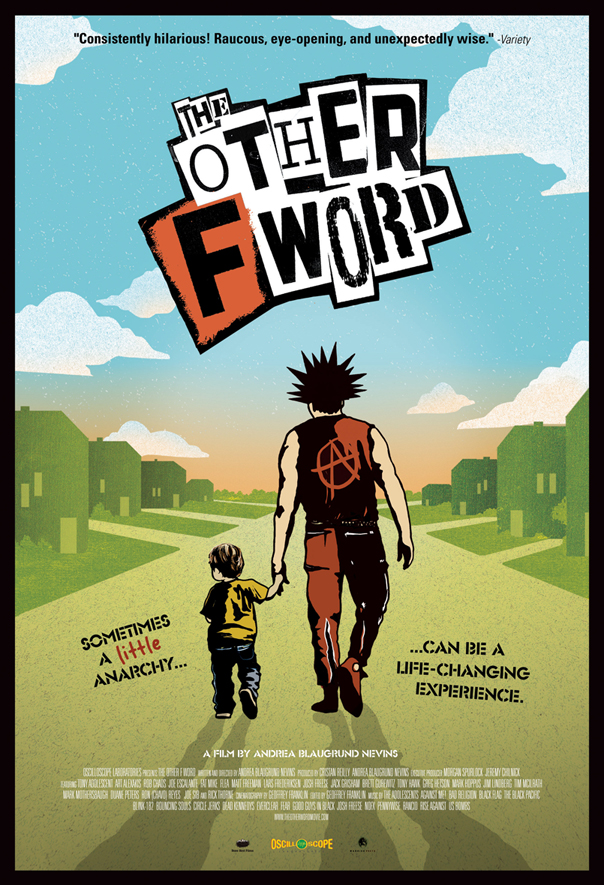

The process of rebelling is often against your own past and, in that spirit during the magic of SXSW, The Other F Word is a compelling documentary I happened to stumble into after being talked out of seeing a different film on the bus ride over to the theater. The documentary chronicles punk rockers turning 40, having families and having to tour to pay the mortgage (to the man!).

Academy Award-nominated and Emmy-winning director Andrea Blaugrund Nevins‘ The Other F Word opens around the country this month and next via Oscilloscope Laboratories. The Film Stage sat down with Nevin, her producer Cristan Reilly and director of photography Geoffrey Franklin and talked about the process of capturing the intimate lives of men who have spent a good part of their lives creating a mythology about themselves.

The Film Stage: How did the project come about and where did you start?

Cristan Reilly: I knew Jim Lindberg (of Pennywise) in high school, we were friends. I had heard he’d written a book called Punk Rock Dad, and I got the book, read it, loved it. And brought it to Andrea, who had been in retirement to have three children and could you possibly consider, maybe thinking about coming out of retirement. I gave her the book and two days later she called and said “I’m in,” and that’s how it started.

Andrea Blaugrund Nevin: And Jim was starting on a tour, and we thought it would be interesting to see what it was like to be a father and manage a full-time tour like that. And that’s how the story began and it grew into something very different.

Would you talk about that – I think what excited me about the film and I see this with filmmakers like Spike Lee, Kevin Smith – those that were part of Gen X, are turning 40, and that rebellion in their work changes, I think that’s well captured in your film.

ABN: Sure, we liked the irony that was our original thesis, or the oxymoron: How do you be punk rock and be a dad. The more we followed around Jim who introduced us to these other guys; we found the story was much bigger than that. We found each of these guys when presented with a baby, really had an opportunity to examine their own anger and where it came from. Weather it was actual abandonment from their own fathers or just disappointment; they all had a story to tell why they wanted to bend over backwards for their own children.

So he was the first that gave you access – how did you get from pre-production with him to the film?

CR: Gosh, did we have pre-production?

ABN: (laughing) No, no. We just knew there was a kernel of a story we would try to follow, and we started shooting pretty much on day one. As we were shooting on tour we would meet other dads, and initially Jim was a little skittish about letting us into his home because he was very protective of his kids and punk rockers tend to be protective period. It’s their nature. The very first one to let us in was Josh Freese (The Vandals, A Perfect Circle), he had three kids then, he now has four. And he allowed us to come into his house and really talk about how the decision was for him. He plays for four different bands, sometimes five. And he had to make a choice to talk about the decision to staying home. That led us to talk to Fat Mike (NOFX) and he said you can’t possibly look at me as punk rock – you have to go talk to Lars Fredrickson (Rancid) and it kept spiraling all the way to Flea (Red Hot Chili Peppers) who was very, very protective, but ultimately saw we were telling a story that I think everybody felt we needed to tell. Something that’s very authentic, but a different type of authentic.

The question of authenticity comes up – especially since these guys are boring suburban dads – with this legacy of punk rock, how do they grapple with that – how do you grapple that?

ABN: (laughing) They all seem to be grappling in their own ways, I think Lars [Frederickson] says it best, if he could win over his wife’s family with a tattoo that says Skunk on his forehead, he’s going to figure out a way to win over his kid’s teacher.

CR: And that’s why he wasn’t on the premiere on Saturday, because he had to go the school gala, he said ‘I gotta go prove myself, I’ve got to go be a dad.’ They are not perfect, they don’t pretend to be perfect. I hope we didn’t portray them as perfect.

I just love that opening shot, with Jimmy spraying his hair with a can of dye before the show, how many days were you shooting this?

ABN: We shot over the course of a year and a half, but we just shoot and shoot – we had 175 hours.

CR: We had to stop. We had to consciously stop because we could keep going and we had openness and willingness and we decided it was time to stop and tell our story because we could have kept going because there is so much going on.

(to Geoff) Can you talk about getting involved as the DP of the film?

Geoffrey Franklin: Sure, I worked with Jim on a couple of things at a music video and action sports company before, so Andrea and Cristin had already started shooting and Jim already had me hanging around him, so he said “well why don’t you try out this guy – see if he can do it because he’s already following me around Warped Tour.”

CR: We imbedded Jeff, he flew out to Boston and climbed on the tour bus because to have Jeff living on the bus would be a very different experience than if Andrea or I were to walk in?

Was it you by yourself?

GF: For the first three days of that tour portion, then Andrea and Cristen came out and we did, I think, the next three days of shooting out there, but all of the stuff at the dad’s homes, was just the three of us.

CR: We were a tiny unit, which is important – because to come in with a big unit and lots of lights and all that stuff would have really changed the dynamic of the interviews and the openness we got from them.

On the tour bus there are these punk rock antics that go on – as a women filmmaker – you removed yourself from that?

ABN: No and that was a conscious decision. The on-the-bus stuff we decided had to be filmed by Geoff, on the bus, alone – fly on the wall.

CR: And they like Geoff

GF: You have a few drinks with them and everyone kind of loosens up.

These are performers; do you ever run into that fear they are performing for you?

ABN: I did not find that as much as I did when we interviewed the other dads. With Jimmy it was hard because he is a performer, and he knew the camera was going to be hanging around him a lot, so he would kind of put on his speaker’s face, and often we really wanted him to just be at home, and not entertain us.

CR: It just took a while, we were buzzing around him for two years, it took a while. And I also knew him for a very long time. And at the very end of the film, after he finally saw it he was very complimentary and said “you know I really think you guys really found the heart of why we do what we do” and I said “thank you Jimmy, thank you for trusting us” and he said “I didn’t” – so that’s what we had to deal with all the time.

Anything else you want to tell us about this film?

ABN: I do think for documentaries you have to take on a style that suits your subject. We’ve been talking to the guys that made Dragonslayer, and to tell their story they had to be there in an entirely different way than we had.

Anything change your perspective on making this film?

ABN: I don’t think we came in expecting this, but I think we came out shattering a stereotype; people tend to cross the street when they see a punk rocker, but instead they won’t cross the street and maybe say, “Hey, how are you?”

CR: Right, look beyond the spikes and tattoos and stuff.

ABN: And see the warm beating heart below it. (To Geoff) Any filmmaking lessons?

GF: Uh, don’t play drinking games with Fletcher [Dragge, of Pennywise] – you will not win. No, it was a real treat for me, it was my first doc, so Andrea and Cristen showed me how to make a documentary, and we had fun with the music and the subject matter.

CR: The story wasn’t always easy to tell, so Andrea was the first and last person really in my mind to take the 175 hours of footage and tell this story.

Were you always interested in punk?

ABN: I grew up in New York City when punk was around, but I wasn’t part of the movement. I like exploring subcultures, and especially finding philosophers in subcultures. Someone said to me early on “you know, punk’s area is always the smartest kids in the room” and they had to be. They were very sensitive and expressive and it was magical, and you meet really great, interesting and smart people in the process.

In terms of fatherhood, have there been any changes in their music?

CR: A lot of these guys Tim [McIrath, of Rise Against] and Jimmy, and Jimmy’s work is about society and he said to me, now that he has kids ‘you know, I’m now even more angry about the world we’re leaving for our children,’ so in a lot of ways it continues to fuel that fire, and they’re even more protective now.

ABN: Right, he’s ready to write a song about those mortgage bankers now, screwing up my daughter’s future (laughing)

CR: For a lot of them it softened some emotions and hardened others, there’s still a lot of anger towards the man.

ABN: And the music industry.

CR: Tim was going off to Wisconsin and he said ‘I’m off to go fight the man’ and so I don’t think it ever stops. It’s a good point thought about the music industry, the thing they love so much and it’s imploded.

ABN: Greed, bad management (laughing) maybe I’ll just shut up.

But that’s not on camera?

ABN: Right, you know a lot of people ask about a soundtrack. We’ll see.

It is great music – we can hope for a soundtrack – thanks so much for sitting down with us.

The Other F Word is in limited release.